by AMIT ROY

NEIL BASU, assistant commissioner in the Metropolitan Police and the most senior Asian police officer in the country, has talked to Eastern Eye – not about his work as the national lead for counter-terrorism policing in the UK – but about something completely different.

“I really enjoyed it. It’s a crime thriller with great characters and a buddy/sidekick relationship which I loved and found fascinating as they are from such obviously different worlds,” he says.

Basu is referring to Abir Mukherjee’s 2016 debut novel, A Rising Man, which introduced the unlikely pairing of Captain Sam Wyndham, a former Scotland Yard detective who had been scarred mentally by his experiences in the First World War and who periodically seeks solace in opium after he arrives in Calcutta (now Kolkata), and his Indian assistant in the Imperial Police Force, the Harrow and Oxbridge educated Surendranath Banerjee, who has had his first name anglicised to “Surrender-Not”.

The year is 1919. Wyndham and Banerjee are required to solve the murder of a white man, Alexander MacAuley, found with his throat cut in an open sewer in “Black Town” in Calcutta. An attractive woman with good legs who catches Wyndham’s eye is Anne Grant, MacAuley’s Anglo-Indian secretary. Wyndham and Banerjee conduct further investigations in subsequent novels – A Necessary Evil (2017), when a maharaja’s son and heir to the throne is assassinated; Smoke and Ashes (2018) which features “a deranged killer on the loose”; and Death in the East (2019) in which Wyndham heads for Assam where “he sees a ghost from his life in London – a man thought to be long dead, a man he hoped he would never see again”.

Basu reveals what he makes of the characters and why the setting has reminded him of his own late father, Pankaj Kumar Basu, who emigrated to the UK from Calcutta, married a Welsh woman, Enid Margaret Roberts, when such cross-cultural marriages provoked widespread hostility, and worked as a police surgeon for 40 years. He died in 2015, shortly after his retirement.

What do you make of Sam Wyndham?

I really like him because he doesn’t fit in. Wyndham is a classic flawed hero with a sarcastic edge, a dry sense of humour and a lack of deference to authority. He is a bit like some of the stereotypical hard-bitten detectives I grew up with, though hard drinking was more common than opium addiction. Given he is an ex-soldier who has survived the war with obvious PTSD (posttraumatic stress disorder), I think a lot of cops would sympathise and empathise with his state of mind, given the horrors we see over very long careers.

Similarly, what do you make of Surendranath (“Surrender-Not”) Banerjee?

I want to see him fight back and claim a bigger role for himself with a lot less deference. The intentional or repeated mispronunciation of people’s names is one of the quickest ways to show disrespect and is a form of bullying. I’d like to see Surendranath reclaim his name and improve his standing. Now that I am older, experienced and have rank, it’s easy for me to be outspoken, but when I was young and ambitious, it was very frustrating. The thing about Banerjee is I recognise the deference in him. Being born and living in a white culture in Britain, I recognise that – having to get on with the job and not rock the boat.

It was not the done thing for your mother, a young woman from Wales, to marry a Bengali doctor?

Absolutely not. For some people, it was more than they could handle. So, there is my mother taking my father, a mid-20s Indian doctor from Calcutta, back to her tiny little village in the foothills of Snowdonia. She is terrified because she has no idea what people are going to make of her choice. And she opens the door and her grandfather wraps his arms around my father. He says, ‘You will always be welcome in this house’ – because an Indian soldier saved his life in the war. It was one of the Indian regiments which fought in France. My mother didn’t know that.

What would you like Sam and Surendranath to investigate?

The assassination of Mahatma Gandhi (on January 30, 1948). He was my huge hero.

How would you like Sam’s relationship with Anne Grant to progress?

I like the fact that he’s romantic, but slightly incompetent around the enigmatic Anne. I am a massive old romantic. I would love to see them get together. I would love to see him marry an Anglo-Indian girl. It would be such a wonderful thing for society.

Why did A Rising Man remind you of your late father?

The book made me think of my dad, and I can’t thank Abir enough for that. In the location, there is a huge connection with my dad who grew up in the shadow of Howrah Bridge in Kolkata. When he qualified as a doctor, he took the chance to emigrate to the UK as part of the so-called ‘brain drain’ (from India) in the 1960s and he worked in the NHS all his life. I regret not talking to him more on his views as a young man leading up to independence and the behaviour of the British in India, but what I do know is he was a lifelong Anglophile and wanted his sons to be rooted in Great Britain. I regret not talking to him more, which should be a lesson for every child reading this. Talk to your parents while they are still around. Abir’s books made me want to understand more of the society that my father grew up in, and therefore more about him and the kind of man he was. He took us to Calcutta when I was an impressionable 14-year-old. His family home is still there – some of my relatives are living in it. The family business was automotive engineering. It was a very successful company when my dad left India. My grandfather had a study. He was perhaps quite an austere man. I never knew him, but I can imagine my father having to make an appointment to see him. My dad, until he had grandchildren, was not a hugger. Quite old fashioned, a quiet man, a man of very few words. His grandchildren transformed him.

What were your father’s reading habits?

My dad was a man who loved books, but the beautiful walnut shelves in the lounge were crowded with non-fiction. Pride of place was given to a full, beautifully bound set of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, which got me through pre and primary school. I own his 1962 edition of Gray’s Anatomy, as well as exquisitely bound copies of Mark Twain novels, a copy of Moby Dick and a full set of Poets of the English Language. He kept a copy of the Bhagavad Gita by his bedside his whole life.

Was he religious?

Oh, he was very religious. I remember borrowing his Bhagavad Gita and taking it to London to read. My mother rang me that night and asked, ‘Did you pick a book off your father’s bedside table? You need to bring that back. Since he left India that book has been at his bedside table wherever he has gone.’ And I had to rush back from London to take him the book. I found out he was still very much a practising Hindu.

When you read crime thrillers, is it as an ordinary member of the public or with the eye of a police officer?

Always with the eye of a police officer. I can’t help it. But I still love them. That’s my point – the willing suspension of disbelief. If you did a crime drama in the way life actually is, no one would watch the programme. Most murder is far from entertaining. It’s brutal and horrible and there is no humour in it apart from the black humour of cops. I enjoyed the first three (Abir novels) so much I bought the fourth hardback. My job is absorbing massive amounts of information. I had forgotten how relaxing it is reading something that completely switches you off.

Can you recall the murder cases you investigated in the past?

I can recall every murder investigation in intimate detail. I have dealt with 22, but 17 of them it was as the senior investigating officer (SIO).

In the Byfield case, for example, drug dealer Tony Byfield and his innocent seven-year-old daughter Toni-Ann were shot dead in London’s Kensal Rise in 2003. It was an attack with no forensic evidence, CCTV or witnesses, but I led an extraordinary team of detectives who tracked down and caught the suspect Joel Smith two years later. Smith is serving a 40-year sentence without parole for that double killing. When I was in anti-corruption, I reinvestigated the murders of two individuals because the famous detectives who had investigated that in 1976 were accused of corruption and fitting up the two men convicted of the murders. All that was proved at the Royal Courts of Justice was there was an element of reasonable doubt in the convictions. In fact, it was interviewing the two legendary detectives about this case – “the torso in the Thames” – that made up my mind to follow in their footsteps. I was taught on my SIO’s course in 2000 that ‘the greatest privilege was to investigate the death of another human being’. I can say in my sixth year in counter-terrorism that this is categorically untrue. The greatest privilege is to prevent the death of another human being. Stopping murderers before they kill is the essence of counter-terrorism work.

What is the difference between the old-fashioned murder cases from the past and the terrorism of today?

The vast majority of murderers and victims are known to each other, including an unacceptable and horrific number of partners, almost always women killed by their other half. The motives of sex, jealousy, greed and revenge are timeless.Most murderers I have met know right from wrong. Terrorists who commit murder are in a different category. In fact, they believe they are absolutely right, and the society they are attacking is fundamentally wrong. Stopping terrorists is easily the most challenging task of my career.

In A Necessary Evil, you were apparently shocked by the elephant execution (when the animal is made to trample a man to death)?

It’s a little odd to say, but it’s nice to be shocked after 28 years of doing this job. My mother tells this story of my father coming home – he had been out on the M6 to certify death in a horrible, multiple-collision traffic accident. There was a young boy who had been decapitated. No one looked for the head because there was a deep fog, but my father went and found the head of this child. When he came back to the house, my grandmother, who lived with us and was cooking, said to my father, ‘Do you want the head on or off,’ because she was cooking trout. My mother said it was the first time she had seen my father, an experienced doctor, look ill. When I asked him about that story many years later, he said, ‘The first time you are not shocked by what you see is the day you should retire.’ Given he was a doctor for 50 years, I took that advice very seriously.

So, your take on Abir’s novels?

I am impressed. Not just because of the emotional connection to Kolkata and my father, but because they transport the reader to the world of Wyndham and Banerjee, and to the Raj and pre-independence India that any British person should want to know more about given India’s place in our history and culture. I can smell and taste the atmosphere of the city.

Finally, what would your own book, were you to write one, be about?

The book would be more about what it feels to be a police officer, particularly a black or Asian police officer, growing up in Britain over the last 30 years. My big ambition is get more people wanting to join what I think is a fantastic profession. I would want people to read my book and think, ‘God, I want to be a cop.’

Jamie Lloyd’s Evita with Rachel Zegler set for Broadway after London triumphInstagram/

Jamie Lloyd’s Evita with Rachel Zegler set for Broadway after London triumphInstagram/

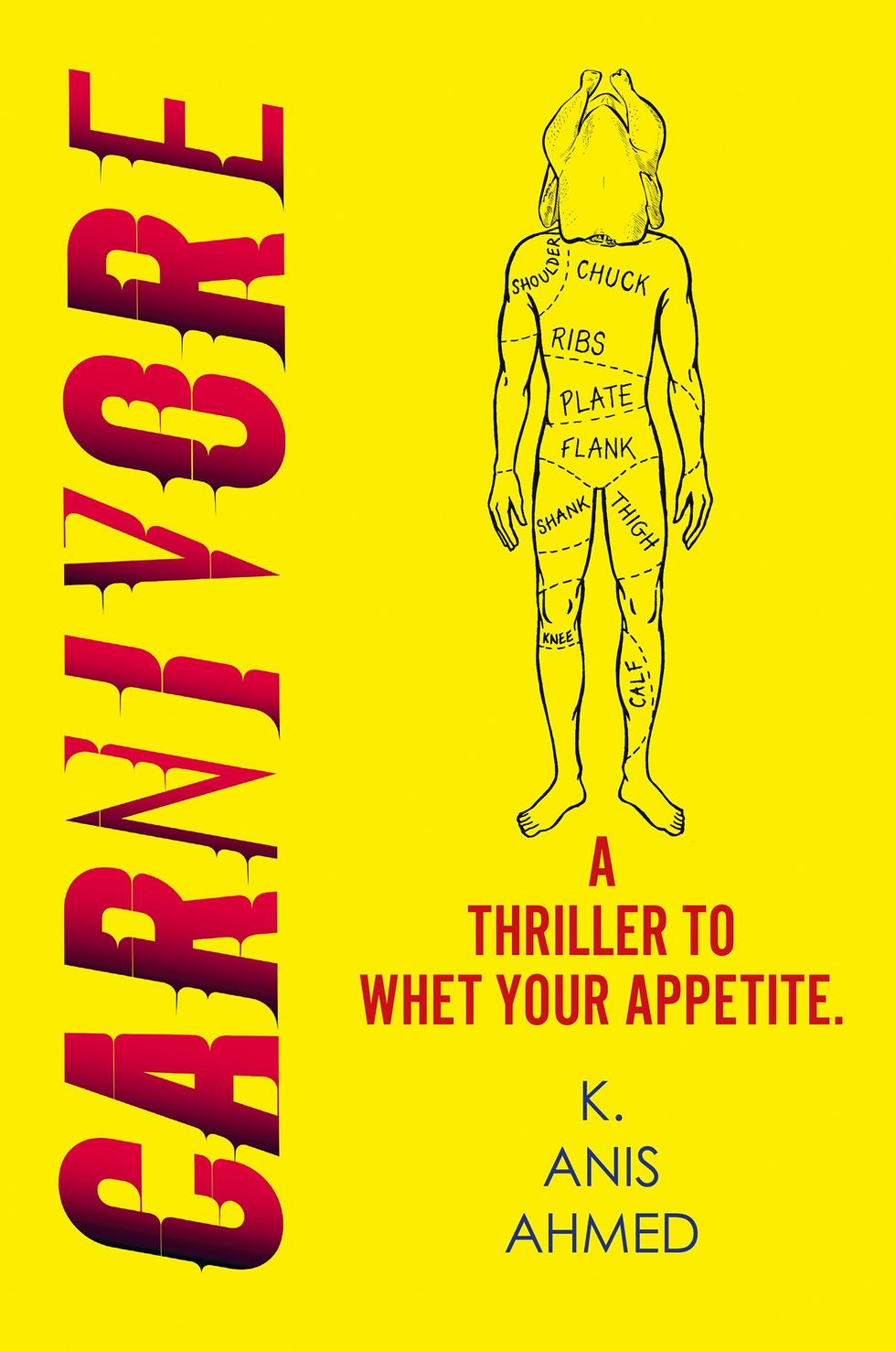

A compelling premise, layered and unpredictable charactersAMG

A compelling premise, layered and unpredictable charactersAMG Anyone who enjoys a gripping story with a diverse cast and unexpected twistsHarperFiction

Anyone who enjoys a gripping story with a diverse cast and unexpected twistsHarperFiction

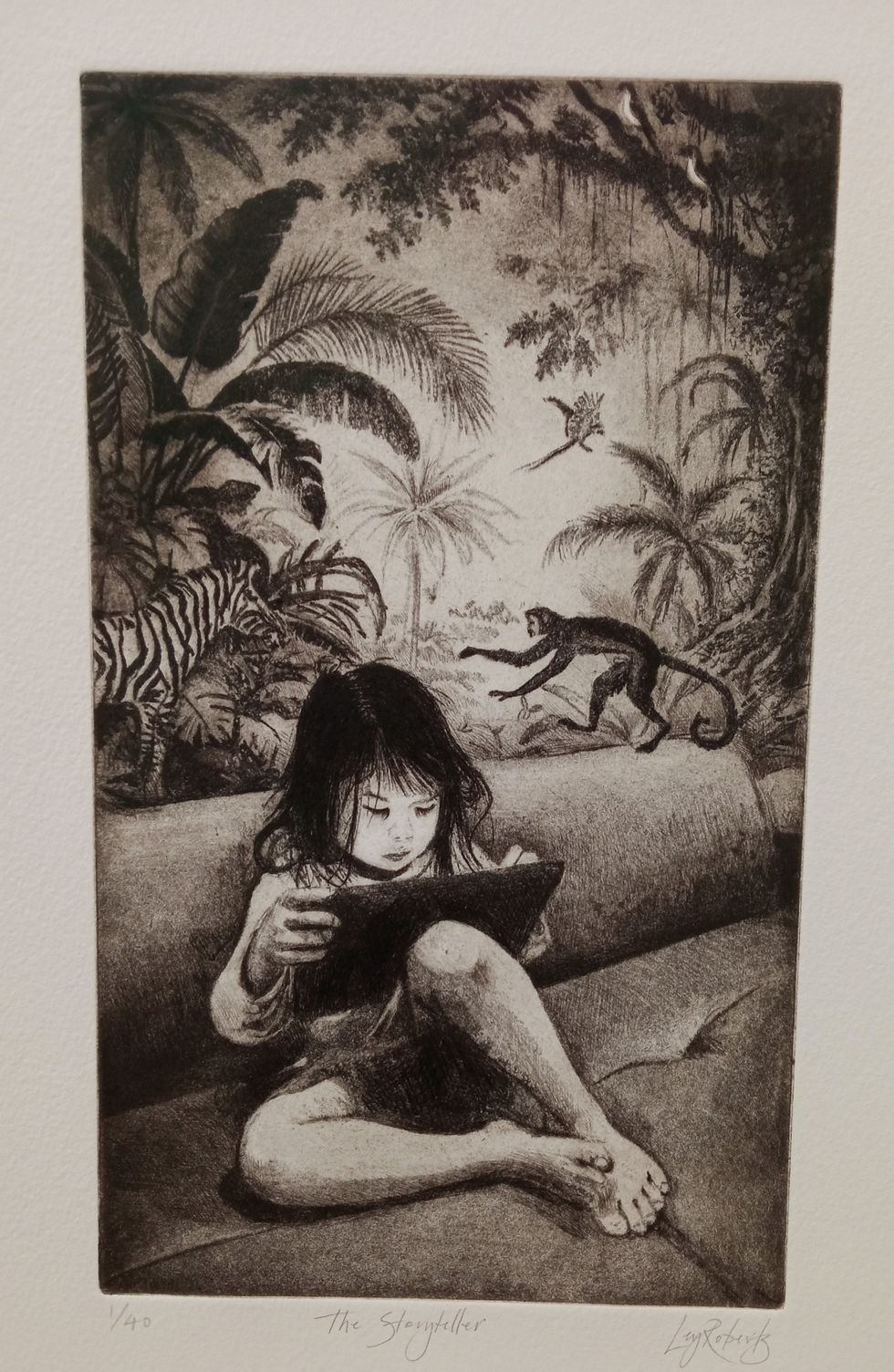

The Story Teller by Ley Roberts

The Story Teller by Ley Roberts Summer Exhibition coordinator Farshid Moussavi, with Royal Academy director of exhibitions Andrea Tarsia in the background

Summer Exhibition coordinator Farshid Moussavi, with Royal Academy director of exhibitions Andrea Tarsia in the background An installation by Ryan Gander

An installation by Ryan Gander A sectional model of DY Patil University Centre of Excellence, Mumbai, by Spencer de Grey

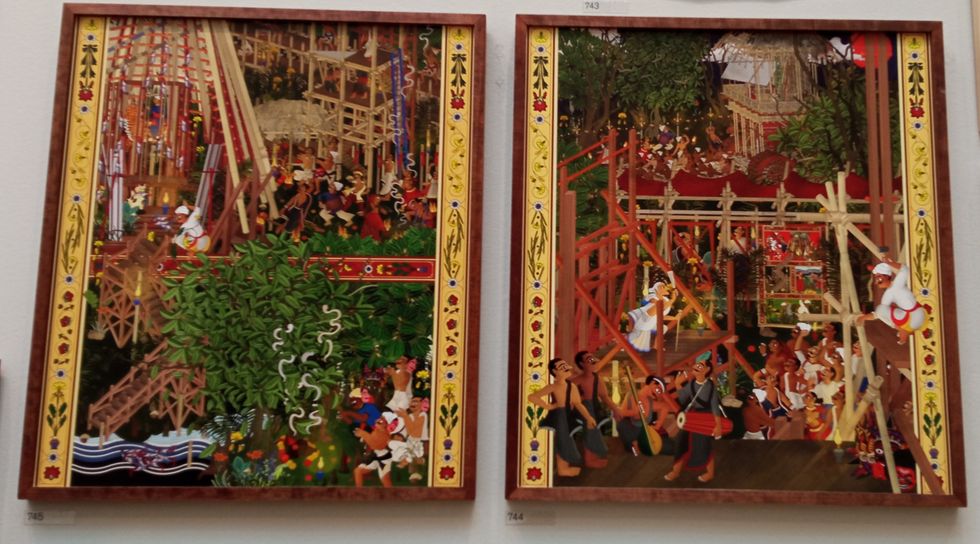

A sectional model of DY Patil University Centre of Excellence, Mumbai, by Spencer de Grey Rituals and Identity and Theatre of Resistance by Arinjoy Sen

Rituals and Identity and Theatre of Resistance by Arinjoy Sen

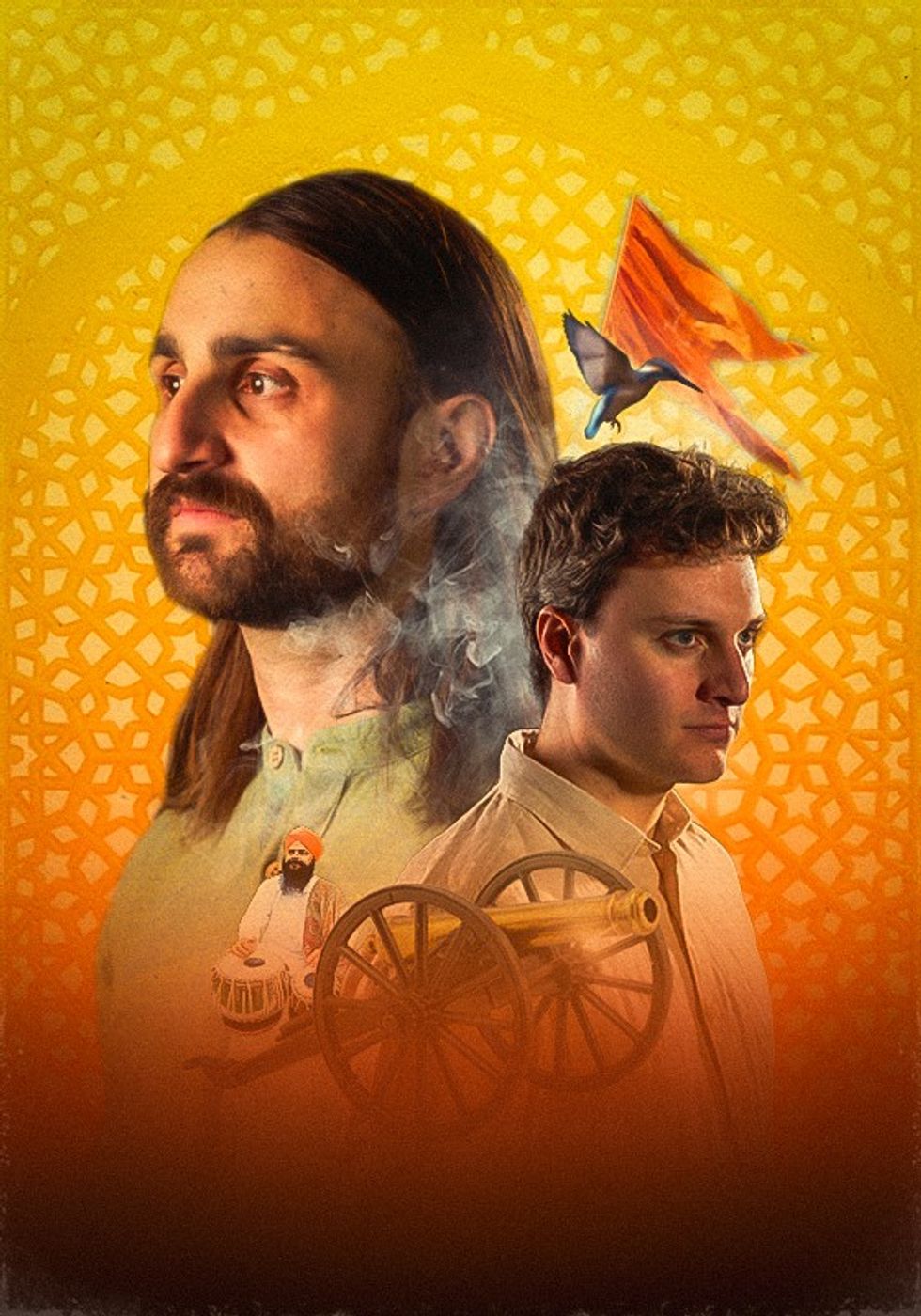

An explosive new play that fuses biting satire, history and heartfelt storytellingPleasance

An explosive new play that fuses biting satire, history and heartfelt storytellingPleasance

Lunchbox is a powerful one-woman show that tackles themes of identity, race, bullying and belongingInstagram/ lubnakerr

Lunchbox is a powerful one-woman show that tackles themes of identity, race, bullying and belongingInstagram/ lubnakerr She says, ''do not assume you know what is going on in people’s lives behind closed doors''Instagram/ lubnakerr

She says, ''do not assume you know what is going on in people’s lives behind closed doors''Instagram/ lubnakerr