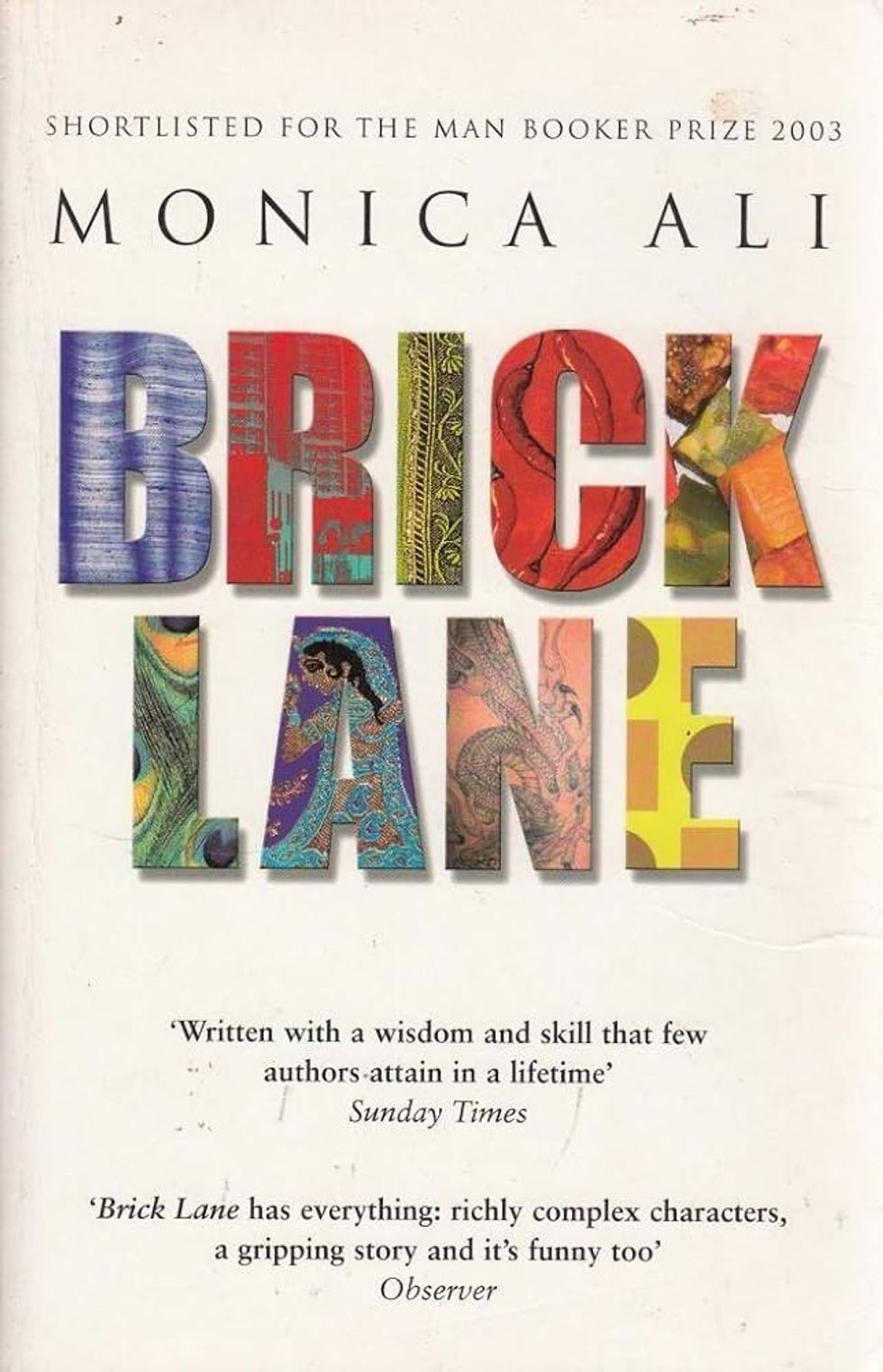

MONICA ALI, who made her debut as a novelist with Brick Lane in 2003, was the main attraction at the London Book Fair last Wednesday (12).

As “adult author of the day”, she was interviewed before an international audience by fellow writer and critic Chris Power.

“I don’t know why they asked me – it’s a great honour,” she said modestly in an interview afterwards with Eastern Eye.

The reason Ali was asked is because she is now a much respected author – and commentator on social issues – who has come a long way in the last 22 years.

Brick Lane, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, was made into a film in 2007, and her fifth novel, which came out in 2022, may be adapted for television.

Early on, Granta recognised her as one of the “best of Young British Novelists”.

Born in Dhaka on October 20, 1967, to a Bangladeshi father and an English mother, Ali was brought to the UK when she was three and grew up in Bolton. Encouraged by a history teacher at school to apply to Ox ford, she got in and read PPE (philosophy, politics and economics) at Wadham College, where she is now an honorary fellow.

When she visited Dhaka in 2019 for a literary festival, she was “welcomed with open arms”. This is significant because when Brick Lane – set in Tower Hamlets – was published, some members of the British Bangladeshi community weren’t quite sure whether they liked the novel without having read it.

As a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, Ali has judged many literary prizes, and chaired the 2024 Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Last year, at an investiture at Windsor Castle, Princess Anne gave her a CBE for services to literature.

Perhaps most important of all, Brick Lane is now “set text for A-level (English) courses”.

Ali can now bring a sense of perspective to how the Bangladeshi community has developed since she wrote Brick Lane nearly a quarter of a century ago.

It tells the story of 18-year-old Nazneen, who comes over from Bangladesh to marry Chanu, who is twice her age, and their life in east London. Her inability to speak English makes her struggle that much greater.

“If I were to write Brick Lane today,” said Ali with a laugh, “I would have to start my research from scratch. I did a lot of research for that book. I interviewed youth workers, social workers, people who worked with kids with drug problems, people who worked in women’ centres, people on the (council) estate, people in restaurants. I did a lot of reading as well. Today, I would have to do that research again.

“Yes, of course, that picture has changed in some ways, particularly for the second and third generations.”

She wondered about Chanu and Nazneen’s daughters: “Shahana and Bibi, what would they be doing? They were bright girls. I reckon they would have gone to university and have lives rather different from their parents.

“On the other hand, I don’t think all the things that I was writing about have completely gone away. I am the patron of a women’s charity called Hopscotch, and it has a lot of Bangladeshi, Somali, different ethnic minority clients. They help maybe women in the older age spectrum. They are sometimes women whose husbands have died or men, who have worked hard, saved up, divorced the old wife and brought in a new one.”

If she was to look again at her characters in Brick Lane, “I very much see the daughters have chosen to get educated,” she mused. “They have got good jobs. Some of the younger men may be really angry with how they feel they are treated in society, facing racism and prejudice, and perhaps anger gets in the way of personal advancement. That’s just extrapolating from where my characters were 20 years ago and thinking about how they might unfold in the future.”

After her appearance on the main stage at the London Book Fair, young women from diverse backgrounds come up to her, as they often do, and said: STORYTELLER: Monica Ali; and (above right) her book “‘When I read Brick Lane, I thought maybe I can be a writer as well.’ That’s a really rewarding feeling.”

Ali recalled how she developed a love of books despite her own unpromising childhood: “I never thought being a novelist, making a living out of writing, was something I would be able to do. I grew up in a poor house with no books or maybe just one or two books. But I had a library card.I used to go to the library every single week, take out a lot of books, and lose myself in other worlds, other societies, other cultures, other people’s individual minds. What set me on the path to being a writer was having that library card.”

Ali and her husband, Simon Torrance, a management consultant, have two children. “My son just turned 26 and my daughter is 24,” she said.

“They are English. They would say their mum’s of Bangladeshi heritage.”

Speaking of her own generation, Ali commented: “There was a fee-ling we weren’t allowed to say we were English because of the notion of © Edward Hill Englishness. That would be considered a step too far. Now Rishi Sunak has come out and said he’s English – which he is.” She declared: “He’s absolutely right, he’s bl**dy English. By what measure is he not English? And this highlighted to me how all those years ago, someone like me had to say, we were British whereas our white counter parts didn’t have to say, they were British. They could say, ‘We’re English.’ It’s thrown a light on the way that word ‘English’ wasn’t used by us. We thought there would be a pushback. That’s why we were applying that ‘I’m British but…’ sort of label.”

She doesn’t think she herself has changed fundamentally since Brick Lane was published. “My desire to write and my interests and way of engaging with the world are not that different. I am still following my nose and writing about what interests me.”

She revealed: “I am working on something new. It’s a novel set in post-pandemic England in a country cottage. It called The Weekend. It’s about two sets of couples who rent a country cottage for the weekend. They are old friends, with two kids. And what could possibly go wrong? Well, quite a lot can go wrong. It’s all about friendships, how friendships evolve over time, the pow er dynamics between couples, how money or the lack of money can affect friendships, how the arrival of children can affect it.”

Today, writers such as her do not feel compelled to write only about non-white ethnic characters. She agreed: “I hope so. That’s something that is starting to change for the better. There’s less of that ‘stay in your lane’ mentality.