ARUNI KASHYAP’S NEW BOOK SHOWS INDIA’S HIDDEN SIDE

by ASJAD NAZIR

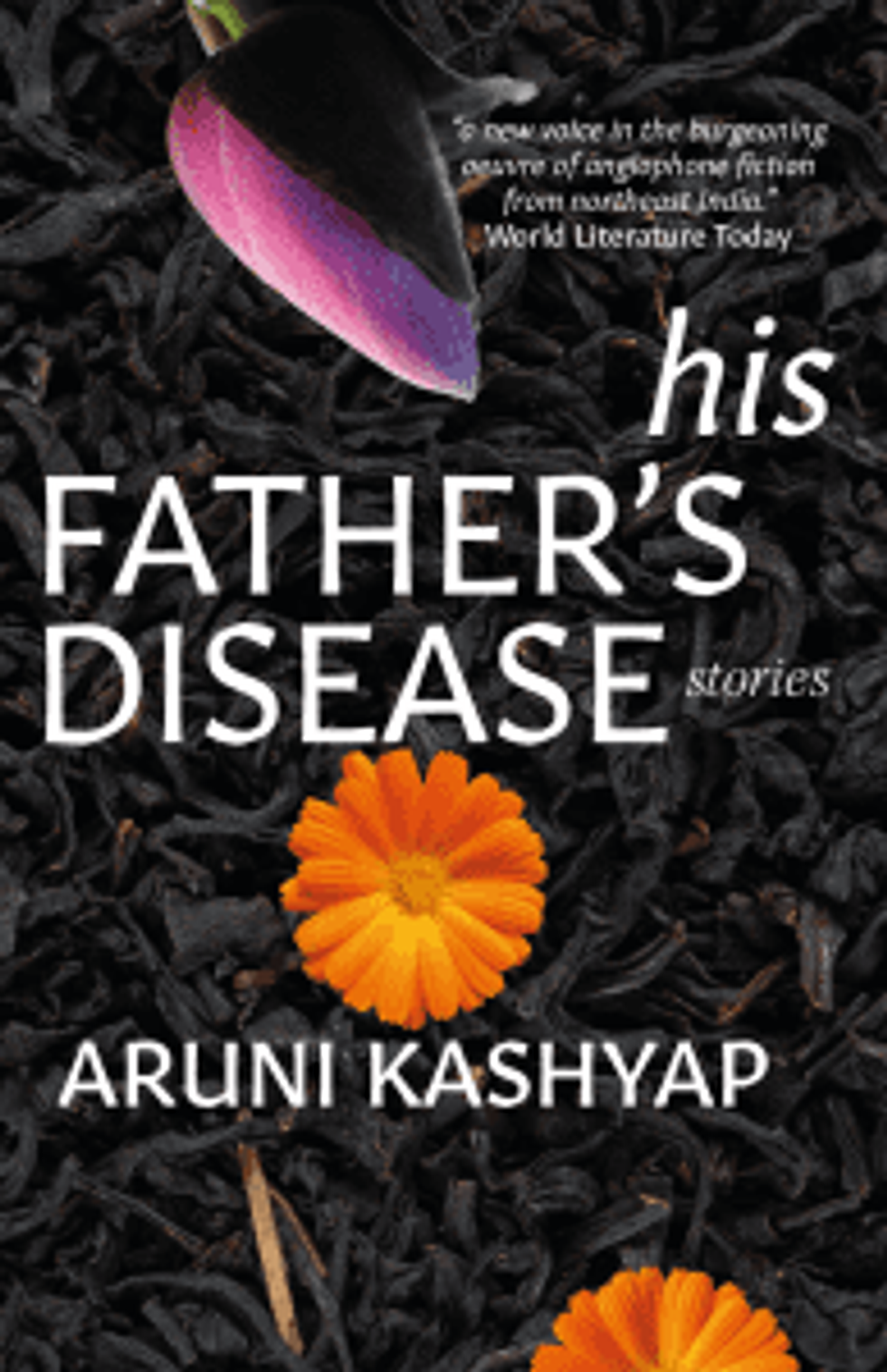

HAVING grown up in the shadow of Assam’s armed rebellion and constant violence, Aruni Kashyap has had plenty to inspire him on his writing journey and channelled that into newly released book His Father’s Disease.

The award-winning US-based Assamese writer has delivered a collection of immersive short stories, which address themes including repression, fundamentalism and the violation of human rights.

The book also asks important questions about environment and territorial sovereignty, along with giving urgent insights into an often silenced and marginalised culture. This is a latest literary chapter for a talented writer who survived an upbringing surrounded by deadly violence and has previously published poetry, short stories and essays.

Eastern Eye caught up with Aruni Kashyap to discuss his new book, the interesting title and connecting a painful past to modern day India.

What first connected you to writing?

My mother fell sick in the early 1990s and thought she would die. I was left alone in the village with my uncles and grandparents, while my father travelled with her to a southern Indian city called Vellore in search of better treatment. My father had bought her a notebook, Chinese ink pen, and royal blue Chelpark ink and asked her to write. And she wrote. She was worried, if she died in Vellore, I would never know the struggles she went through. She published that auto-fiction novel and other works, but I write because I know writing can save our lives.

What led you towards your new book, His Father's Disease?

The short story is an amazing tool to present diverse perspectives. I wanted to use a form that was not expansive like a novel, but something narrow and very deep to write about brutal, essential, underrepresented and indispensable, aspects of Indian democracy. A collection of stories allows me to tell this story in polyphonic voices in the tradition of Nadine Gordimer, who wrote about the racist apartheid state through short stories. Writing short stories is like digging a well in the old-fashioned way; you go in, collect mud and send it up, and keep digging until you get to crystal clear water.

Tell us about the book?

His Father's Disease is a collection of stories set in India and the United States about a community of people that have been brutalised and displaced by the violence of a long-drawn insurgency. The Indian government has suppressed many such insurgencies through widespread human rights violations. I wanted to write about people caught in the middle of it, but in a way that it isn’t confrontational like many other political works. Hence, the metaphor of disease that runs through in the stories; the disease of racism, homophobia; a diseased state that doesn’t grant equal humanity to the minorities and poor.

What inspired the stories in the book and how many are rooted in reality?

Everything in the book is inspired by my own experiences of living as an Indian as well as an Indian immigrant in the United States. I have also made space for stories of people who don't have the opportunity to tell their accounts, such as the poor in rural India. The characters and settings are my own, but most situations are drawn from real life. For instance, I come from a large family of hundreds and the story about the person who practises healing chants is based on my uncle.

What inspired the interesting title His Father’s Disease?

I draw so much from my community because there is a rich texture in the common folk language. His Father's Disease refers to a character’s homosexuality from the mother’s perspective, who doesn’t have the language to express it even to herself. This is because there is no word for queerness or homosexuality in the dialect she speaks, despite the common presence of homosexual behaviour in her world. So, when she finds out her son is gay, she remembers how her husband had an affair with a man, too, and refers to her son’s homosexuality as ‘his father’s disease’.

Tell us more…

I have understood queer desire through Oscar Wilde and then Allan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty. Later, as a student, I read queer theorists, but I wanted to highlight how queer desire is perceived in rural, non-metropolitan, non-intellectualised spaces. This was important to me and I wanted to highlight that through the story. I mean, here’s a lower caste woman whose response to her son’s homosexuality is both tender and violent. Isn’t that interesting?

You grew up under the shadow of violence. Has writing this book helped you heal in any way?

I don’t think we would ever heal, but writing helps me make sense and accept things. I have no regrets. The entire experience has enriched my life; the happiness and trauma. I know the value of joy because I know sorrow so deeply.

Who are you hoping connects with your book?

I guess people who believe that storytelling can bring social change. People who believe that no conversation about human rights is possible without storytelling at its heart.

How much is what has happened in the past connected to India today?

It is impossible to understand the nature of the Indian state apparatus if you don't know what India has done to its minorities in the past. As an Indian citizen who has grown up in northeast India, the site of many violent insurgencies since the 1950s, we have seen the worst side of it. I grew up with stories of entire villages being burnt down, torture camps and widespread rape by the army during counter-insurgency; but everyone was silent because it benefitted the middle class and the campaign of misinformation in the media.

What about now?

The violence on ordinary people that the world is watching with shock in India in 2020 or 2021 (thanks to focus provided by international celebrities) is so well-orchestrated because the Indian state has rehearsed it on the bodies of tribals, Muslims, women and lower castes. None of the violence surprises me, though it always shocks me. The current Hindu fundamentalist regime has inherited a state apparatus capable of unlimited brutality, but they can do it because they have been rehearsing this on us.

Why do you think is it important to keep stories alive?

If we do not keep stories alive, then human beings will never make sense of anything, I feel.

What can we expect next from you?

I am currently revising a novel tentatively titled The Love Story of an Anti-national, set in (Narendra) Modi's India.

What are your favourite books?

I love the Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison. The Shadow Lines by Amitav Ghosh and My Son's Story by Nadine Gordimer are some other favourites.

What inspires you today?

The sense of duty that I should find beauty amid brutality through my writing.

Why should we pick up your book?

Because it will show you how the conventional understanding of Indian English writing is changing due to the new English writing produced by citizens in its margins, who talk about indigeneity, the darker side of India, as well as the beauty of a life rooted in hope and joy.

His Father’s Disease by Aruni Kashyap is published by flipped eye

Riddle is frequently seen supporting him courtside, including at the 2025 WimbledonGetty Images

Riddle is frequently seen supporting him courtside, including at the 2025 WimbledonGetty Images She has also used her platform to promote the sport among younger audiencesGetty Images

She has also used her platform to promote the sport among younger audiencesGetty Images Morgan Riddle is an influencer and media personality with over 1 million followersGetty Images

Morgan Riddle is an influencer and media personality with over 1 million followersGetty Images