by AMIT ROY

THE contrast between what was happening in London and Delhi last week could not be sharper or more dramatic.

While British prime minister Theresa May’s three years in office ended in tears outside 10 Downing Street on a beautifully sunny morning, India's Narendra Modi was being showered

with rose petals after winning a second five-year term as prime minister.

In 2017, the British prime minister called a general election and, against all expectation, lost the Conservative majority. In India, the conventional wisdom was that Modi would probably be back with a greatly reduced number of seats. No one foresaw his landslide victory with 303 seats for the BJP alone.

By and large, the Indian election was peaceful. The process works primarily because those who are defeated are willing to accept the result. The fact that Modi was able to increase his majority defies logic, but perhaps the last five years have been relatively corruption free. On the minus side have been the “beef lynchings” and the assault on minorities.

These need to be stopped if India is to progress as a country that is for all its citizens.

Back in Britain, the Conservative Party is now tearing itself apart over who should replace May. The chances are that it will be Boris Johnson, who is popular with Indians from

his time as mayor of London.

Nor is everyone happy, though, with the way the prime minister has been ousted.

Rami Ranger, deputy treasurer of the Conservative Party and chairman of Conservative Friends of India, told me: “I am gutted, disappointed that our PM has been forced out of office.

"She worked so incredibly hard to get a Brexit deal with minimal side effects that protected jobs and the economy. We are now in a very precarious situation. Alas, she was knifed by people for their personal ambitions.”

Asked who would be the best person to succeed May as prime minister from the Asian point of view, Ranger surprisingly did not suggest Boris, but the Pakistani-origin home secretary, Sajid Javid.

“Javid has been very good to India – he is above parochial politics,” said Ranger.

The contest to replace her has already turned “toxic”, with Boris causing controversy with his pledge: “We will leave the EU on October 31, deal or no deal.”

Any attempt by a future prime minister to take the UK out of the European Union without a deal is likely to be thwarted no matter what the Brextremists demand. It is hard to see how a change in prime minister is going to heal the deep divisions in the country.

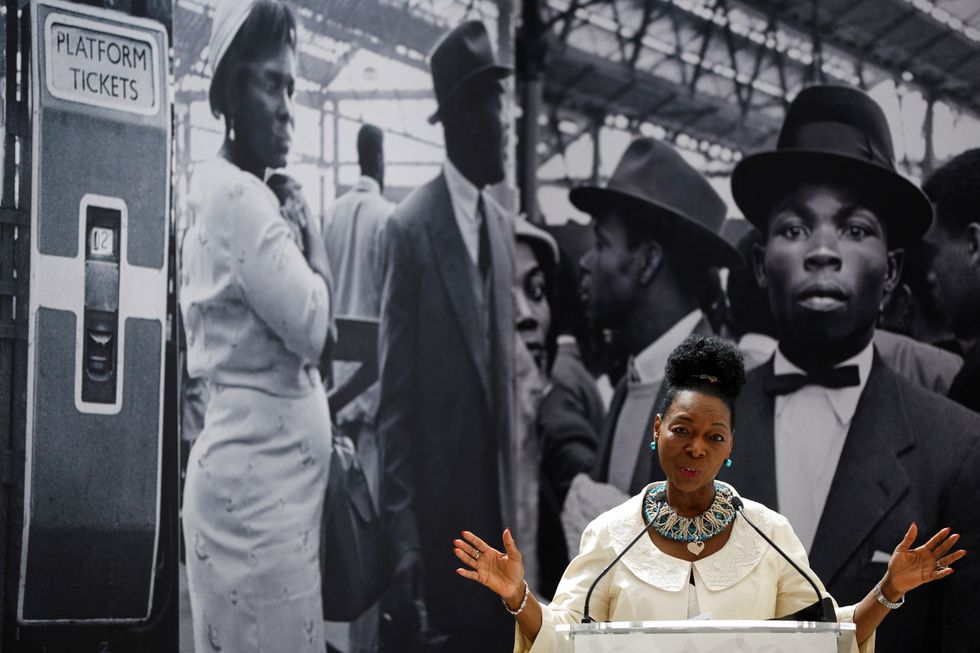

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

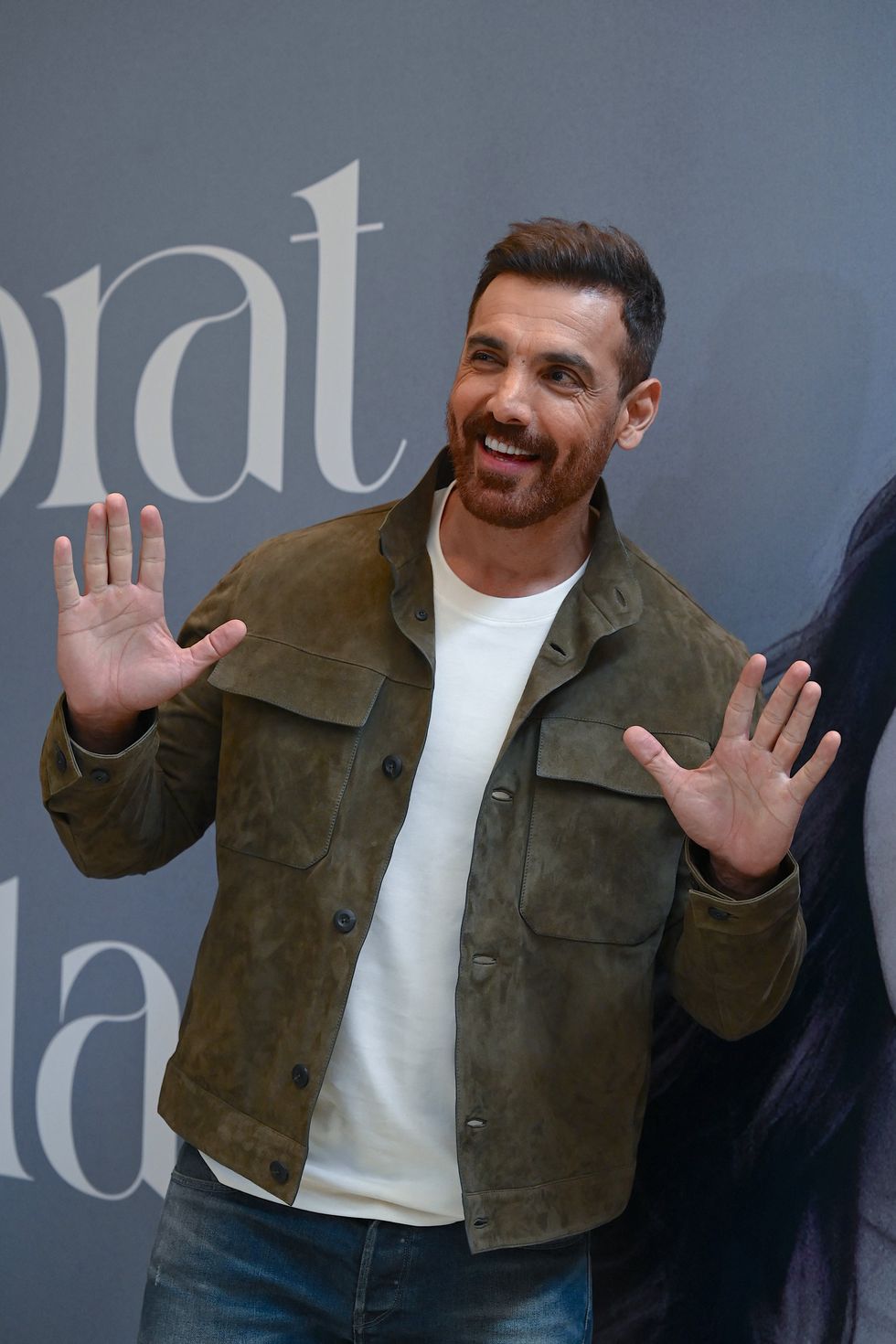

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf

Shraddha Jain

Shraddha Jain Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf

William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta

Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta Money Back Guarantee

Money Back Guarantee Homebound

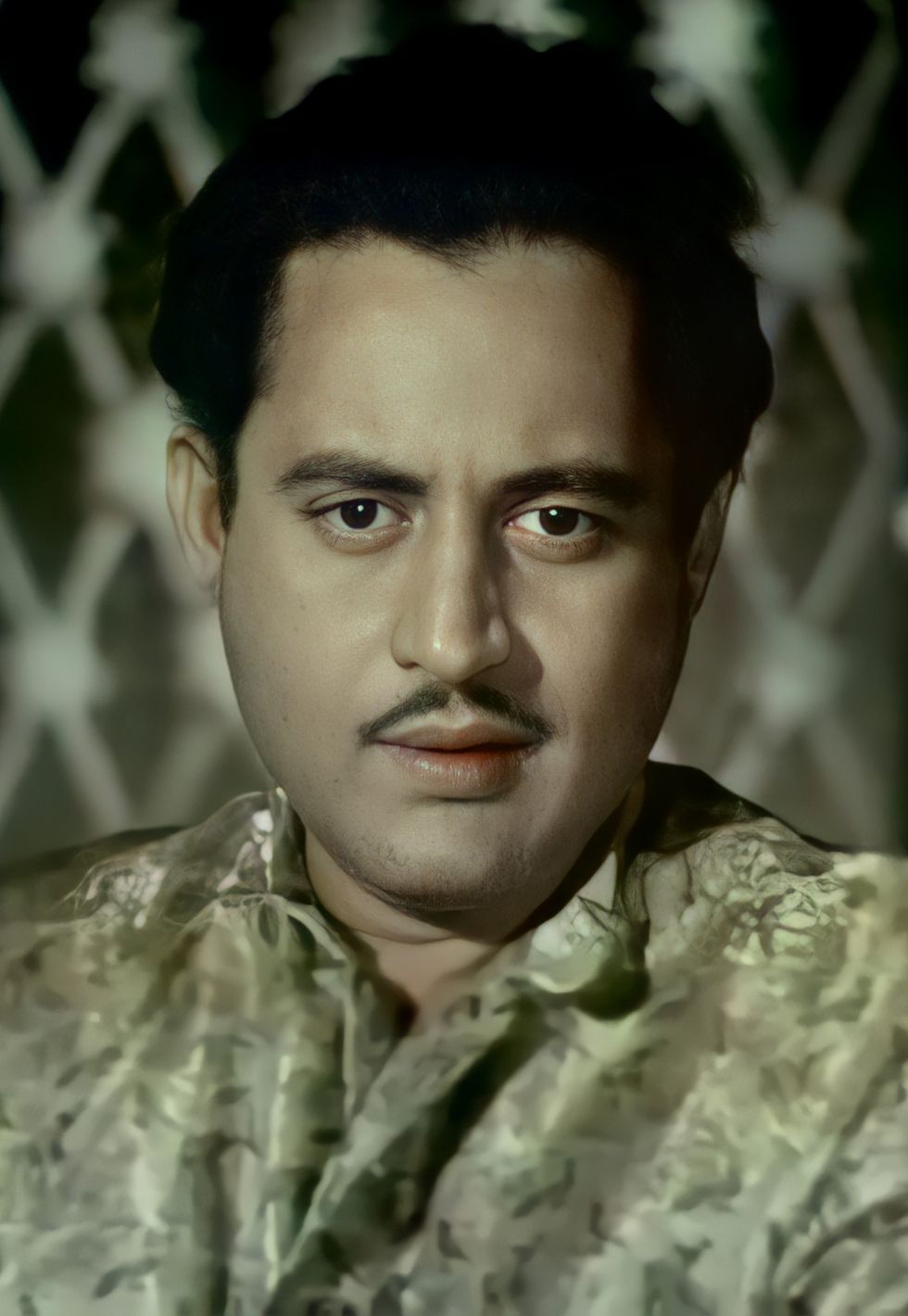

Homebound Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand

Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand Sarita Choudhury

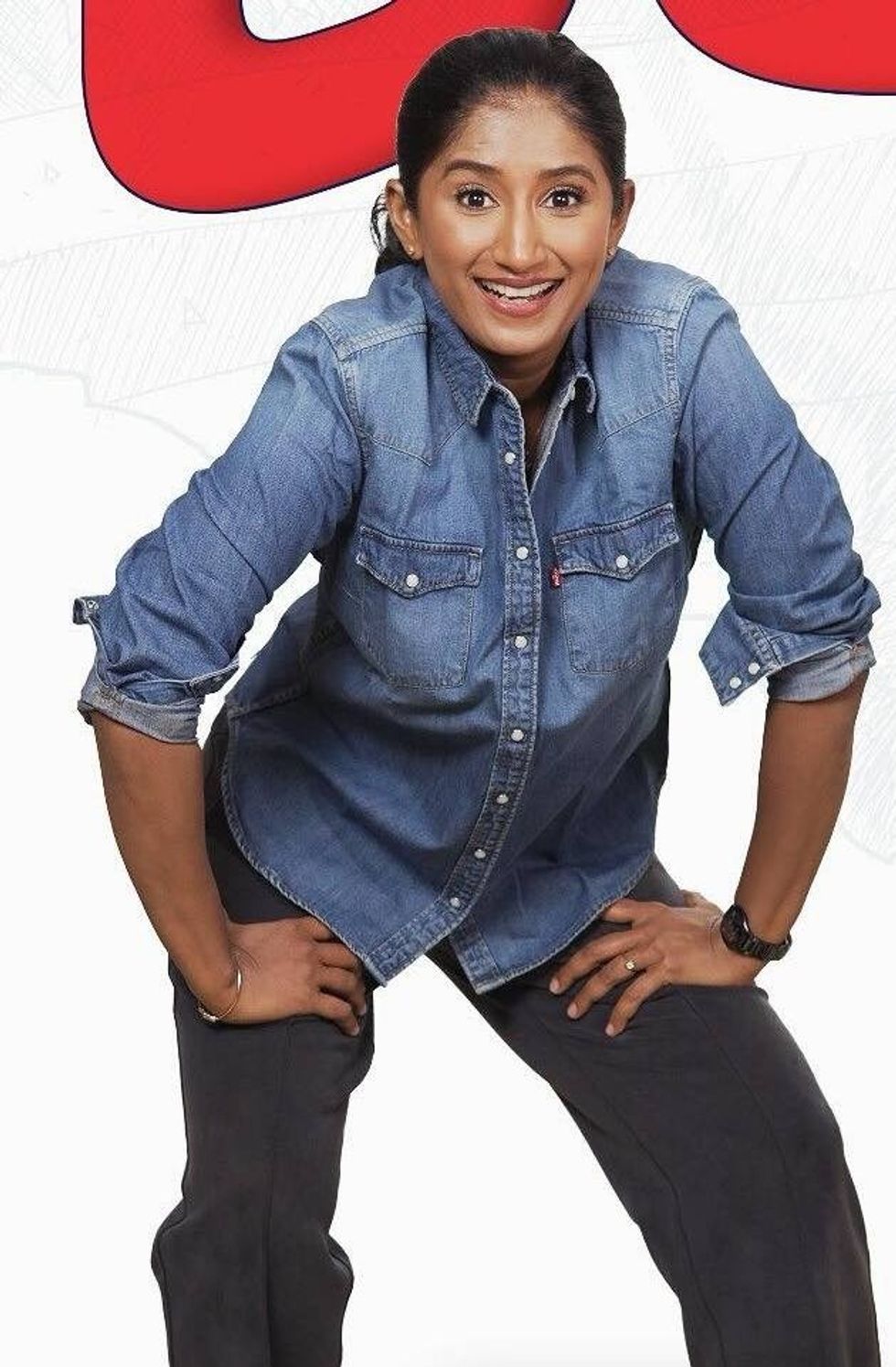

Sarita Choudhury Detective Sherdi

Detective Sherdi