The moment I walked into the Royal Academy to see Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo, I thought of Rabindranath Tagore.

Both men were giants of literature, but they were visual artists as well.

Victor-Marie Hugo (February 26, 1802- May 22, 1885) is best known for his novels The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) – many will have seen the 1939 film adaptation starring Charles Laughton and Maureen O’Hara – and Les Misérables (1862), which BBC TV adapted in 2018, with a starring role for Adeel Akhtar.

Rabindranath Tagore (May 7, 1861-August 7, 1941) was a Bengali poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He was the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, for the poetry of Gitanjali.

Gallery owner Sundaram Tagore, who had flown over from New York to attend Eastern Eye’s Arts, Culture & Theatre Awards (ACTAs) at the May Fair Hotel on May 23, said: “Before leaving London, I managed to visit the Victor Hugo exhibition, which moved me deeply.”

Sundaram’s father, Subhogendranath Tagore (1912-1985), was the grandson of Hemendranath Tagore, the third son of Debendranath Tagore and the elder brother of Rabindranath Tagore.

The Victor Hugo exhibition is definitely worth seeing before it ends on June 29.

Giving a tour of the exhibition, Andrea Tarsia, director of exhibitions at the Royal Academy, said Hugo left behind some 4,000 works on paper, of which 70 were chosen for display.

“But they really are 70 of his most remarkable drawings,” commented Tarsia. Hugo often used brown ink and wash and graphite on paper.

Notable works include The Town of Vianden Seen Through a Spider’s Web, 1871; Mushroom, 1850; Lace and Spectres, 1855-56; The Cheerful Castle, 1847; The Town of Vianden, with Stone Cross, 1871; Mirror with Birds, 1870; Chain, 1864; Octopus, 1866–69; and The Lighthouse at Casquets, Guernsey, 1866.

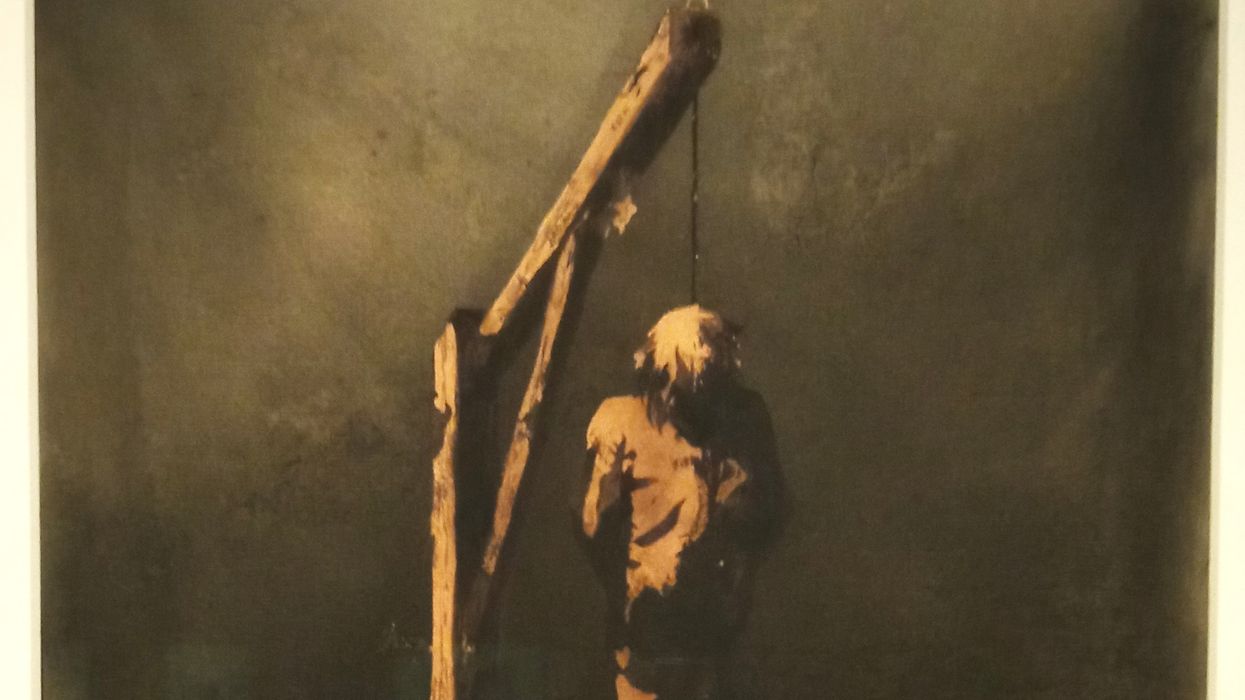

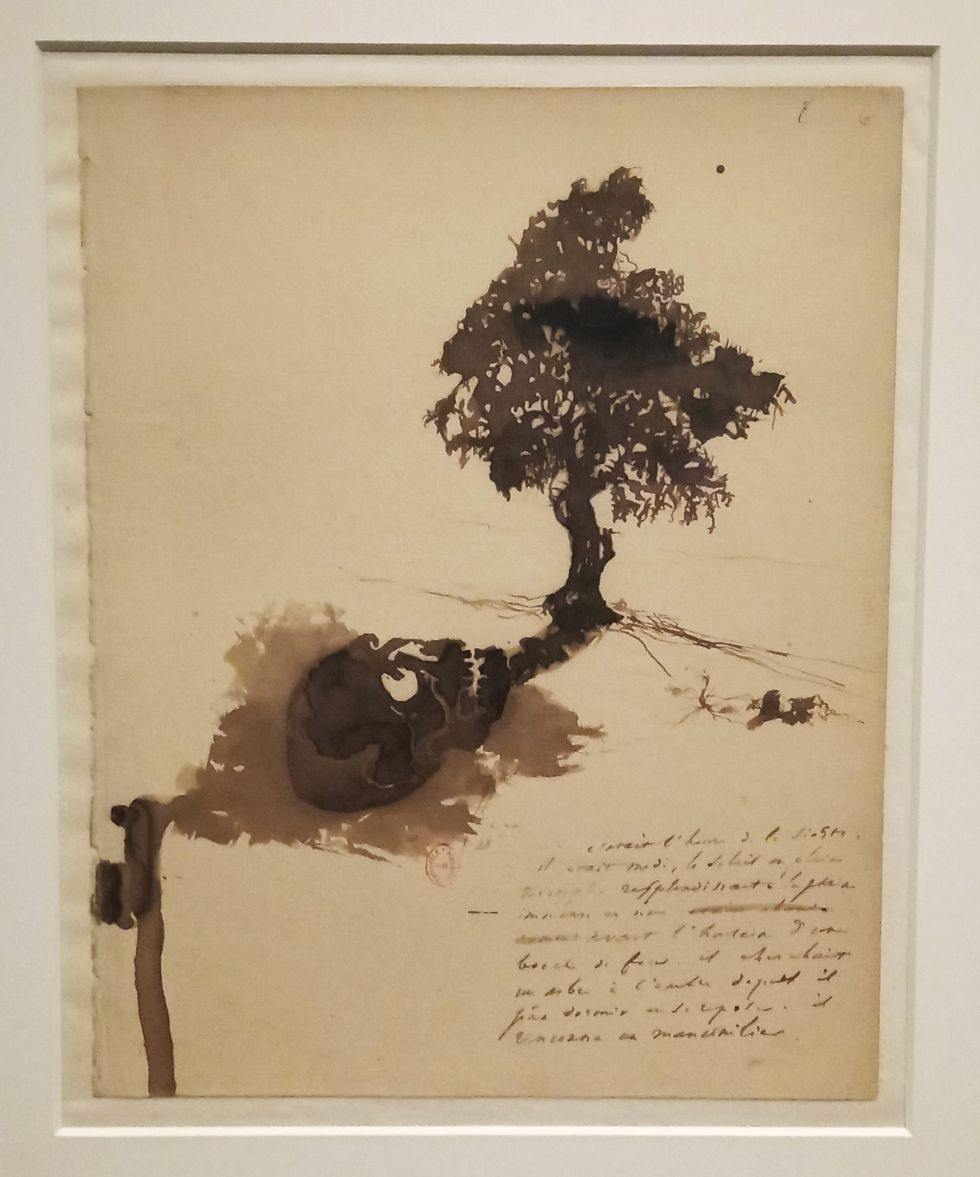

There is also Ecce Lex (Latin for “Behold the Law”), 1854, done after the hanging of John Tapner in Guernsey; and The Shade of the Manchineel Tree (notes from a trip to the Pyrenees and Spain), 1856, where the shade is made to resemble a skull to denote the poisonous qualities of the fruit.

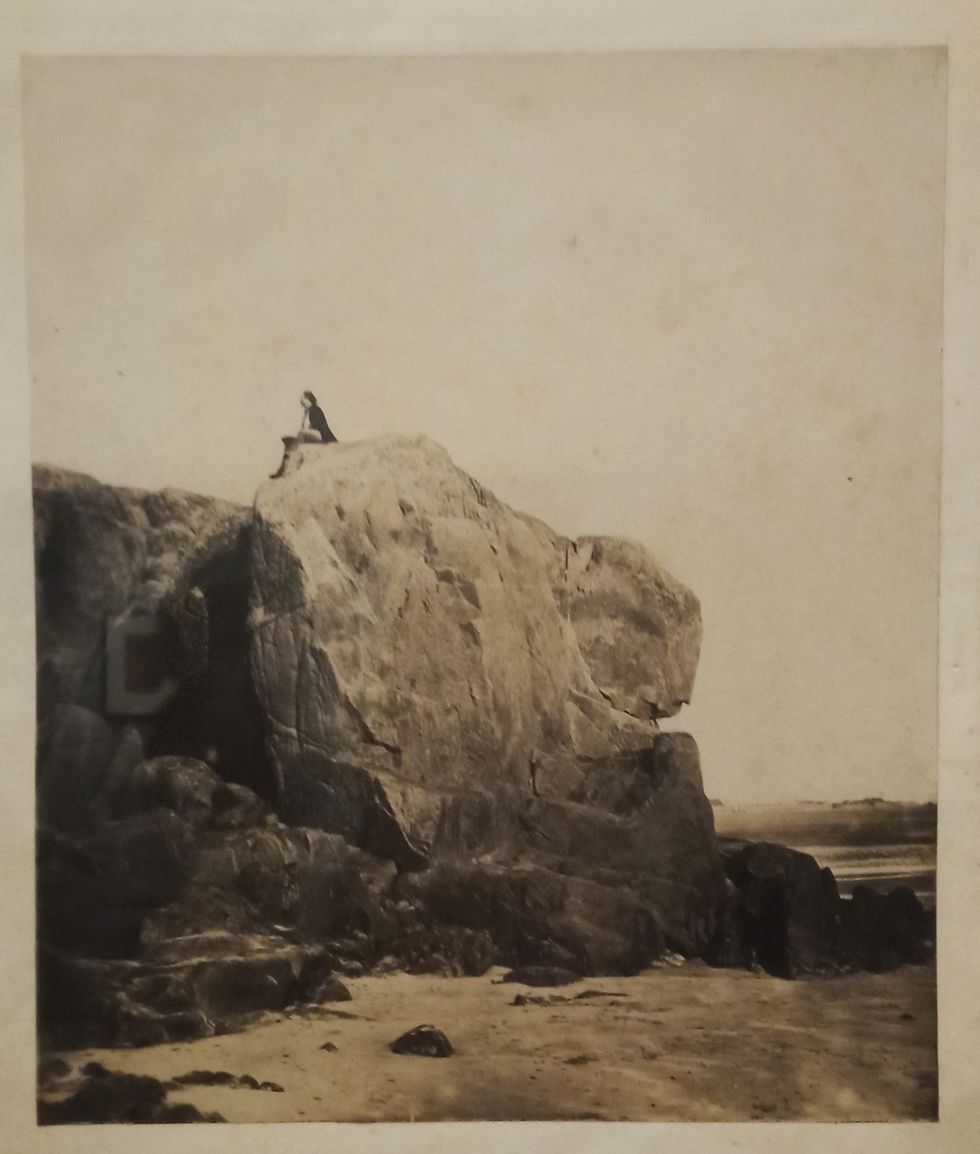

There is a photograph of Hugo seated on the Rocher des Proscrits (Exile’s Rock), Jersey, 1853, which was taken by his son, Charles Hugo.

“Hopefully, together, they will give you an intimate sense of Hugo’s remarkable, multifaceted imagination. Perhaps people are less familiar with his work as a visual artist. The exhibition is the first to be held in the UK with Hugo’s drawings in just over half a century.”

He explained it was “a rare chance to see these works because the inks and the paper are so fragile that once exhibited, even at these very low lighting levels, they then need to be kept in the dark for an extended period of time”.

The exhibition’s curator, Sarah Lea, said: “We made a decision to arrange these spectacular works in a thematic structure, because although Hugo drew across his lifetime, he often returns to similar motifs. And it’s really interesting to be able to see, for example, the collections of the castles, one of his great passions. Despite writing so much, he doesn’t leave us very much direct commentary on the drawings themselves. He was inspired by the way ink moves on paper. He was never intending to be an artist.”

She referred to his “mysterious” drawing of a mushroom: “Who knows what was really meant by the mushroom? It appears to us as a total enigma.”

“We have him exploring nature on the monumental level with mountains, and a minute level with spiders’ webs and birds’ nests,” she went on. “The drawings were largely private during his lifetime. Sometimes he made works that he would send to friends. But the drawings themselves weren’t exhibited until three years after his death. They’re first shown in a public exhibition in Paris in 1888.”

Hugo lived in exile from 1856 to 1870 on the island of Guernsey, where he bought a house. “He redecorated it from bottom to top in a most extraordinary manner of eclectic collecting and reassembling different pieces of furniture and decorative arts. And it was from the lookout, which was a vast conservatory that he constructed at the top of this house, that he would be able, on a clear day, to see the coastline of France. And it was there that he completed some of his most important literary works. A profound source of inspiration for Hugo was the ocean.”

He strongly opposed the death penalty. After the execution by hanging of convicted murderer John Tapner in Guernsey in 1854, Hugo made many drawings of a hanged man, including Ecce Lex.

He also appealed – unsuccessfully – to the US to pardon John Brown, an abolitionist who had been sentenced to death in Virginia on charges of treason, murder and conspiracy to incite a slave insurrection. Hugo appeared to be an early supporter of Black Lives Matter.

Hugo’s brother-in-law, Paul Chenay, made print reproductions of his earlier Ecce drawings, which were published with a new title, John Brown, and circulated in protest at Brown’s execution.

In a letter to Chenay in 1861, Hugo said: “John Brown is a hero and a martyr. His death was a crime. His gallows is a cross. Let us therefore once again draw the attention of all to the lessons of the gallows of Charlestown. My drawing, which through your fine talent has been reproduced with striking fidelity, has no other value than this name: John Brown – a name that must be repeated unceasingly, to the supporters of the American republic, so that it reminds them of their duty to the slaves: to call them forth to freedom. I shake your hand.”

When Hugo died in 1885, aged 83, over two million people lined the streets of Paris to see his funeral procession. But many of Hugo’s admirers wouldn’t have been aware of his private love of drawing.

Incidentally, the Royal Academy last week announced that Simon Wallis, currently the director of The Hepworth Wakefield, will take over in September as its new secretary and chief executive. In his earlier career, he held curatorial positions at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, and Tate Liverpool. He was the director of Chisenhale Gallery, London.

Wallis, who succeeds Axel Rüger, said: “The Royal Academy of Arts is at a pivotal moment of development and positive change. The RA is the central London home for artists, art and art lovers, generating powerful experiences and innovative teaching about art in a rapidly changing society. As the UK’s oldest and foremost artist-led organisation, the extraordinary talent and vision of the Royal Academicians and their team lead the creative conversation on a national and international stage.”

Now that Hugo has been featured at the Royal Academy, maybe Tagore, too, will merit an exhibition one day under Wallis’s leadership.

The Royal Academy won the ACTA for community engagement last year. It was collected by Tarsia.

In Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo, at the Jillian and Arthur M Sackler Wing of Galleries at the Royal Academy, ends on June 29.