by AMIT ROY

THIS is only the second time that India has had a pavilion of its own at the Venice Biennale – the last occasion was in 2011 – but it is being held up by critics at the world’s biggest festival of art as “one of the very best”.

This is emphatically the opinion, for example, of Sundaram Tagore, who owns art galleries in New York, Hong Kong and Singapore and who has been showing his own documentary, Tiger City, on the architect Louis Kahn, at the biennale.

Tagore marvels at the way seven carefully chosen Indian artists – Nandalal Bose, Atul Dodiya, GR Iranna, Rummana Hussain, Jitish Kallat, Shakuntala Kulkarni and Ashim Purkayastha – have been commissioned to “celebrate 150 years of Mahatma Gandhi”.

The theme of the Indian pavilion, which has been curated by RoobinaKarode, director and chief curator of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in Delhi, is Our Time for a Future Caring.

There is an explanatory quotation from Mahatma Gandhi who was born 150 years ago in 1869: “I am not a seer, rishi or a philosopher of non-violence: I am only an artist of non-violence and desire to develop the art of non-violence in the realm of resistance.”

The 58th Venice Biennale, which began last week and runs until November 24, is May You Live in Interesting Times. It takes its theme from an ancient Chinese curse that refers to periods of uncertainty, crisis and turmoil.

The curator of the biennale, Ralph Rugoff, commented: “At a moment when the digital dissemination of fake news and ‘alternative facts’ is corroding political discourse and the trust on which it depends, it is worth pausing whenever possible to reassess our terms of reference.”

It is certainly intriguing that one organisation, Arts Professional, found in its research that those who voted Leave in the 2016 EU referendum in Britain tend to hate the arts and are unlikely to be attracted by the Venice Biennale. It discovered that those who live in 44 pro-Brexit areas, including Sandwell, Boston and Blackburn, were “more likely to have voted

Leave than engage with the arts”.

Critics who agree with Tagore’s assessment of the India Pavilion include Casey Lesser of Artsy, who suggested: “The best way to take the pulse of contemporary art worldwide may be by visiting the Venice Biennale’s national pavilions.”

Lesser continued: “In its second-ever showing at the biennale, India is honouring the 150th anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi’s birth. Rather than showing literal representations of the celebrated leader and activist, however, curator Roobina Karode chose artists who channel

Gandhi’s timeless influence. Sculptures, installations, painting, and video evoke peaceful protest, passive resistance, and respect for the environment.

“The crown jewel of the pavilion is an installation, Covering Letter (2012), by the Mumbai-based artist Jitish Kallat.

“Walk into the pitch-black theatre, and you’ll find a glowing stream of mist and a projection of words flowing through it. Look carefully, and you’ll see that it’s a letter, written five weeks before the start of World War II, from Gandhi to Adolf Hitler. You can walk through Gandhi’s plea for peace, in which he addresses Hitler: ‘Dear Friend.’ “‘You actually find yourself in that long corridor of human possibility, a letter going from ‘one of the most well-known proponents of peace to one of the most brutal perpetrators of violence, cohabitating

the planet at that same moment in time, Kallat explained’,” Lesser said.

“And I think that becomes a space for self-reflection in some ways.”

The India Pavilion is also praised by The Art newspaper: “Mahatma Gandhi, perhaps the most famous Indian of all time, forms the central theme to the group exhibition at the India Pavilion.

“In Broken Branches (2002), Atul Dodiya has recreated the old wooden cabinets found in the Gandhi museum in Porbandar, filling them with prosthetics, books, tools and weaving in personal items, while GR Iranna has covered one of the walls with hundreds of wooden

padukas for his work Naavu (We Together, 2012), which refers to Gandhi’s choice of wood slippers – he rejected leather – and the power of collective marching.”

Lunchbox is a powerful one-woman show that tackles themes of identity, race, bullying and belongingInstagram/ lubnakerr

Lunchbox is a powerful one-woman show that tackles themes of identity, race, bullying and belongingInstagram/ lubnakerr She says, ''do not assume you know what is going on in people’s lives behind closed doors''Instagram/ lubnakerr

She says, ''do not assume you know what is going on in people’s lives behind closed doors''Instagram/ lubnakerr

He says "immigrants are the lifeblood of this country"Instagram/ itsmetawseef

He says "immigrants are the lifeblood of this country"Instagram/ itsmetawseef This book is, in a way, a love letter to how they raised meInstagram/ itsmetawseef

This book is, in a way, a love letter to how they raised meInstagram/ itsmetawseef

The crew of The Ministry of Lesbian Affairs

The crew of The Ministry of Lesbian Affairs

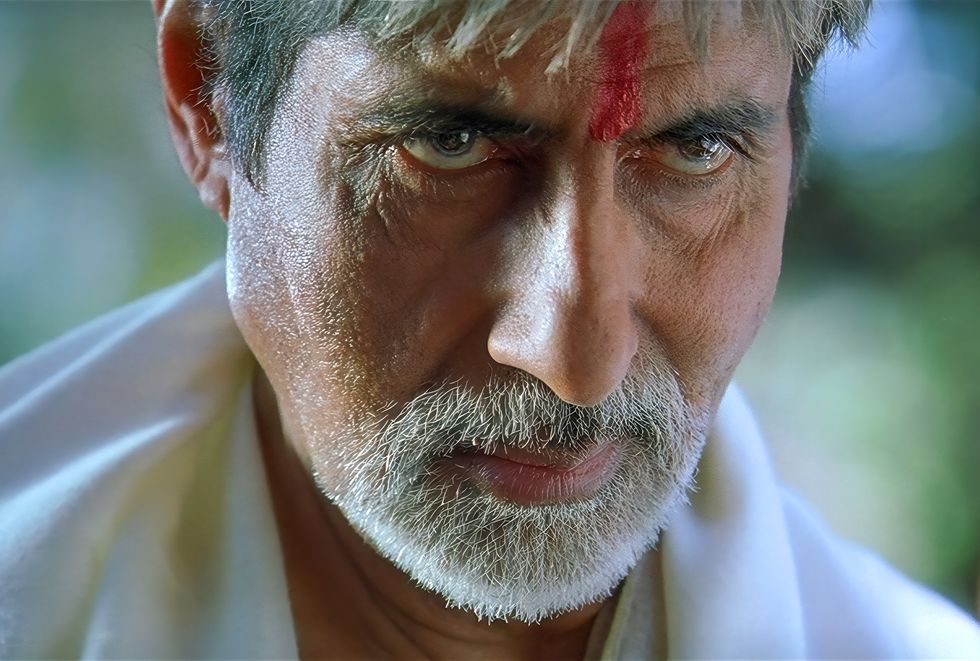

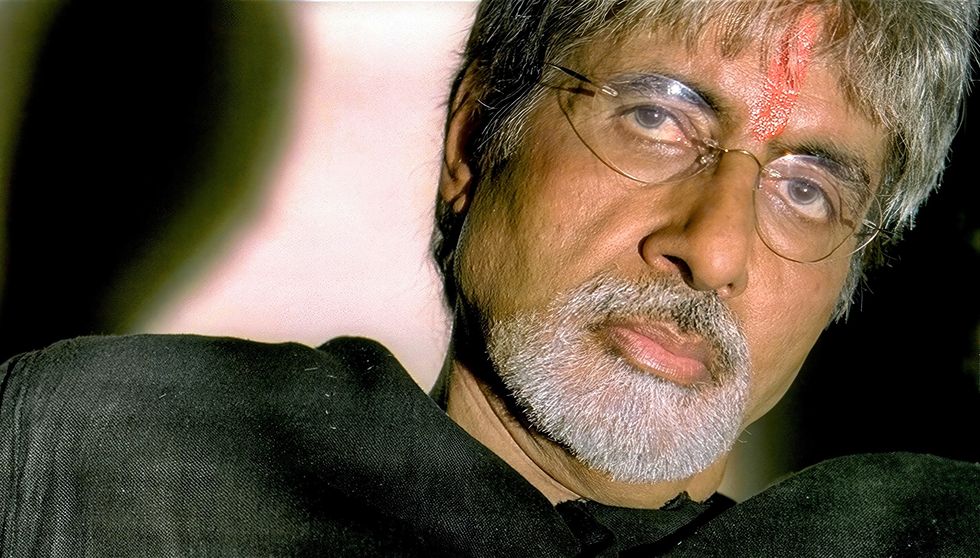

A still from Sarkar, inspired by 'The Godfather' and rooted in Indian politicsIndia Glitz

A still from Sarkar, inspired by 'The Godfather' and rooted in Indian politicsIndia Glitz Sarkar became a landmark gangster film in Indian cinemaIndia Glitz

Sarkar became a landmark gangster film in Indian cinemaIndia Glitz The film introduced a uniquely Indian take on the mafia genreRotten Tomatoes

The film introduced a uniquely Indian take on the mafia genreRotten Tomatoes Set in Mumbai, Sarkar portrayed the dark world of parallel justiceRotten Tomatoes

Set in Mumbai, Sarkar portrayed the dark world of parallel justiceRotten Tomatoes Ram Gopal Varma’s Sarkar marked 20 years of influence and acclaimIMDb

Ram Gopal Varma’s Sarkar marked 20 years of influence and acclaimIMDb

The 50 digital paintings showcase a blend of cosmology and Indian classical musicThe Bhavan

The 50 digital paintings showcase a blend of cosmology and Indian classical musicThe Bhavan