THE granddaughter of an Asian war hero has spoken of his hope for no further world wars, as she described how his “resilience” helped shape their family’s identity and values.

Rajindar Singh Dhatt, 103, is one of the few surviving Second World War veterans and took part in the Allied victory that is now commemorated as VE Day. Based in Hounslow, southwest London, since 1963, he was born in Ambala Jattan, Punjab, in undivided India in 1921, and fought with the Allied forces for Britain.

He received an MBE last December for his services to the south Asian community in the UK.

His granddaughter Amrit, 31, who calls him Babaji, told Eastern Eye: “He has been bed-bound for the past two months, but before that, he was very fit and active. He was diagnosed with cancer two years ago. He has always shown great resilience – both mentally and physically – and taught us to treat others with humility and respect.

“These values run very deep in our family and remind us youngsters to appreciate the peace that comes from these values. Just recently, babaji expressed his hope that there would never be another world war, having seen firsthand what division and violence can do, not just to nations, but to humankind and the human spirit.”

For the family, VE Day (Thursday, 8) was more than just a celebration of victory. It’s a day of remembrance and reflection. As a family, Amrit said, they spend this time in honour of not just Dhatt and everything he gave up, but also the sacrifices of other women, children, and men from that time.

Amrit said, “These stories are particularly important from people of minority backgrounds because these soldiers and veterans helped build this country. They didn’t just come to immigrate; they built up this country, protected it, and shaped its history. People need to understand that immigrants weren’t just contributors to the nation – they defended it and completely changed its prospects. It exemplifies the idea of looking beyond fear, injustice, and prejudices towards people of colour, because there should be immense pride in the fact that previous generations helped shape the country.”

The family reflects on how young Dhatt was when he fought in the war that led to the freedom of today and they are grateful for the difference his sacrifices made, Amrit said.

Dhatt joined the Indian Army in February 1941 as a sepoy (private). He was deployed to the Far East campaign, where he fought in Kohima, northeast India, supporting the Allied Forces in breaking through Japanese defenses.

He left the newly-independent Indian Army in late 1949 with the rank of havildar-major. The army veteran served as a physical training instructor from 1942 to 1943 and army store keeper from 1943 to 1949. After the war, Dhatt returned to India before relocating with his family to Hounslow in 1963.

Amrit said, “He wanted to continue his education, but there were financial restraints in the family. When the war broke out in 1941, he decided to join the army, partly out of duty, but also out of necessity to support the family. Babaji always speaks about the army and the pride he felt in serving, as well as the friendships he made while serving in the British Indian Army. “However, there were things he chose not to speak about. I think he possibly suffered from some traumatic stress disorder, though in his generation and culture, such things are not openly discussed, especially by men.

“He often speaks very happily about his memories with fellow soldiers, including the white British soldiers. He especially talks about how they used to play sports together, sometimes football or volleyball. Despite never mentioning or criticising anything negative, his stories hint at segregation between white soldiers and soldiers of colour when they were away from the sports pitch.”

She added, “Despite others openly speaking about racism, my grandfather always focused on the positive, saying the British treated them well.”

When the war ended, Indian soldiers were granted indefinite leave to remain – this was the British government’s way of saying thank you for their service.

According to Amrit, till a few years ago, there was not much recognition of the role of Asian and Commonwealth soldiers in the world wars.

She noted how until the early 1980s, during the 40th anniversary celebrations of VE and VJ Day, white veterans from the UK, Canada, America, New Zealand, and Australia were honoured for their service.

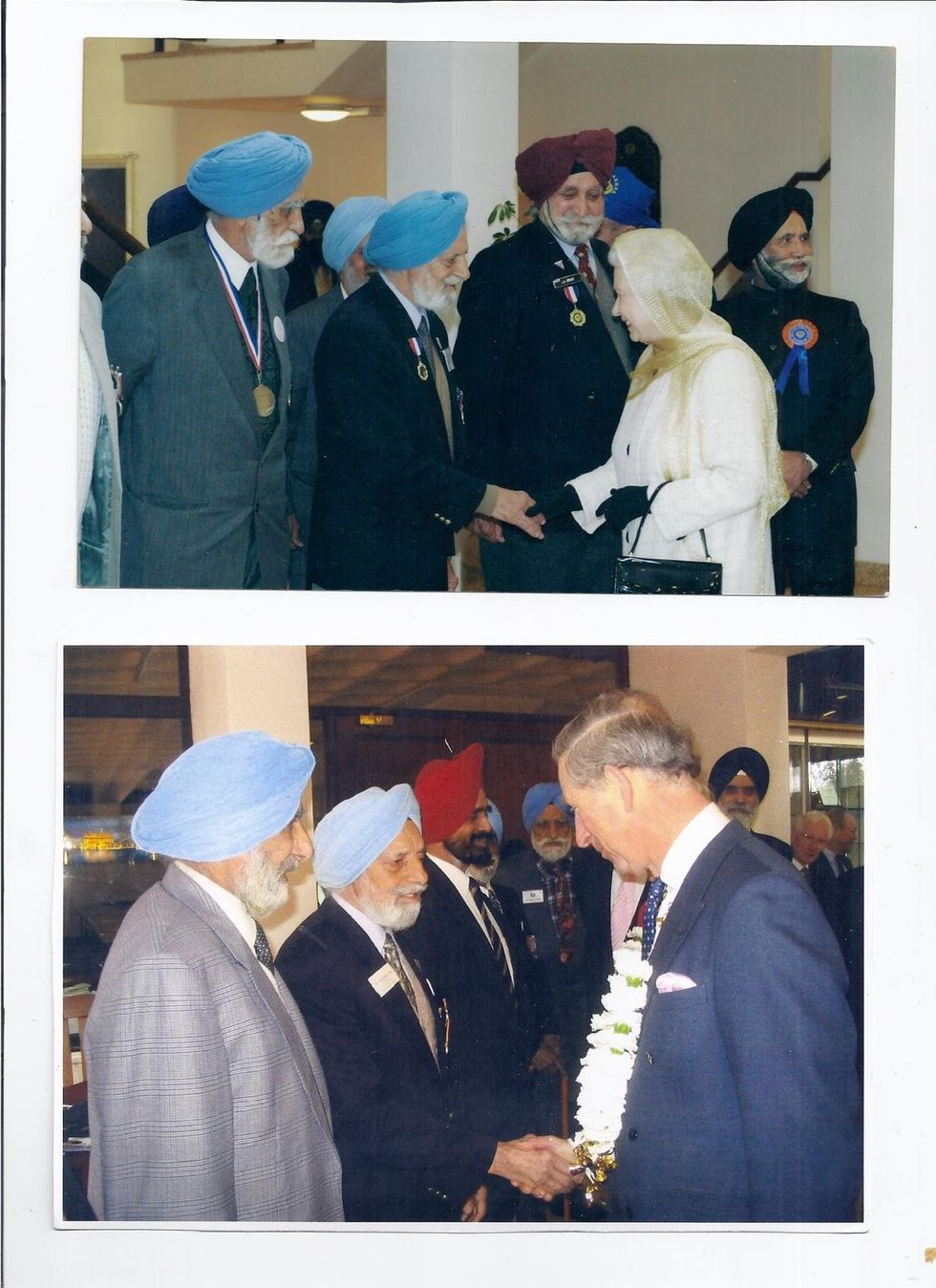

“None of the recognition was directed towards soldiers of colour from undivided India, the Caribbean, or Africa. At that point, Babaji and other veterans in west London created an association called the Undivided Indian Ex-Servicemen’s Association to raise awareness of the contributions of soldiers from these regions.”

Amrit said her grandfather did not complain about how Asian and Commonwealth contributions to the war are remembered. But she said he wished more could have been done earlier.

“The association he co-founded came about purely because there wasn’t any recognition; these soldiers were practically forgotten. It’s very important that the Commonwealth soldiers who played a vital role are considered and remembered, and that wider communities and societies understand that,” Amrit said.

“Babaji is glad that recognition is growing, but there’s still a long way to go. While there’s slight disappointment, he is appreciative of the little milestones that have been achieved.”

“His message is that it’s important everyone remembers and understands that the freedoms and things we enjoy nowadays came from the fact that they sacrificed so much in their time. It wasn’t just for a particular country or background of people, but for the wellness of humankind as a whole – people of all colour and backgrounds.

“It’s important that future generations remember the contributions made, and that no one would have to experience something like a world war again, but rather live with peace and respect for one another.”

Dhatt’s wife, Gurbachan Kaur Dhatt, passed away in 1990. His elder son, Parminder Singh Dhatt (Amrit’s father) is based in the UK, while another son, Jasvinder Singh Dhatt, lives in New Jersey, US. The Dhatt family has seven grandchildren and three great grandchildren now.

Describing her grandfather as a “very positive man”, Amrit added, “Until February, he was very independent. He has always been very high-spirited and never wanted to feel like a burden. Even now, he jokes with us family members, saying, ‘You guys are telling me I can’t do it, but I know I can.’”