By Barry Gardiner

Labour MP for Brent NorthIMAGINE the outcry if the UK government was to tell farmers what crops they must sow and how much they were allowed to produce.

Or if it forbade farmers from selling their produce to anyone they choose and forced them to sell to state-controlled markets at a fixed price.

I guarantee every one of the MPs who spoke in this week’s debate about the Indian farmers’ protests would be standing up in parliament denouncing our government for its human rights violation.

So how did it come about that when these restrictions in India are being done away with, those very MPs are complaining that this is a direct attack on the poor farmers who have, for decades, been subject to those very restrictions?

You don’t have to be politically savvy to understand that with 83 per cent of seats in the Indian parliament dependent on the votes of farming communities, it would be foolish for any government to legislate against farmers’ livelihoods – particularly when your manifesto commitment was to raise their incomes across India. So, what is going on?

Agriculture reform is no easy matter. The Common Agricultural Policy is proof of that. But India’s current woes paradoxically grew out of its greatest success – feeding its population. India launched its Green Revolution 60 years ago. It gave farmers in the alluvial plain that stretches across north-east India large subsidies for fertilisers, seeds and equipment, and gave them access for the first time to credit.

That success came at a price – which was water. High-yield wheat and rice strains displaced the traditional crops of the region and in the past 20 years, groundwater levels have fallen to 15 per cent of previous levels. By 2018 in Punjab and Haryana, 61 per cent of farmers were forced to dig wells deeper than 10 metres – something unprecedented in an area famed for its Himalayan-fed river systems.

And water was not the only price for ending famine. By 2008, Punjab – which comprises 1.5 per cent of India’s area – accounted for nearly 20 per cent of the country’s pesticide consumption. The huge subsidies for pesticides and fertilisers took their toll on the land, poisoning the soil and creating rising health problems in the local population. The current system of agriculture is simply unsustainable.

On top of a failing system there is the additional burden of a corrupted structure.

The Indian version of the Soviet economy after independence dictated agricultural targets, and farmers had to meet them.

So was born the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC). Thousands of APMCs ran local markets, known as mandis. Farmers could only sell to APMC-controlled mandis and only at fixed prices. Minimum prices were established by the central government and these were then topped up by the local state legislature.

In Punjab, the local top-up was particularly high and this led to illegal traffic or produce from lower top-up areas to higher – all driving cash through the hands of the controllers of the APMCs. Originally, APMCs were a necessary protection for farmers from exploitation in the free market. But the protection soon became a protection racket.

Local politicians and cabals took control of the APMCs. As the only buyers, mandis began to set ceilings on what farmers received for their produce and offered desperately low prices which ceased being a guarantee, but became a burden. Payments to farmers were delayed, putting them into debt to the commission agents and local money lenders, who were an integral part of the corrupted system. That debt burden has led to despair which has seen thousands of farmers suicides in recent years.

The irony is that many UK MPs speaking about the farm reforms this week, specifically mentioned the 10,000 farmer suicides that took place in 2018 and 2019 as proof of the wickedness of the new regulations. Yet they failed to recognise these suicides were the result of the existing system, not a result of the farm bills introduced only last year and yet to be implemented.

The system began as targeted support to guarantee price stability. It was corrupted over time into an unsustainable taxpayer-funded subsidy regime being creamed off by vested interests. When the Agriculture Standing Committee in the Lok Sabha [lower house of parliament] reported that the APMC mandis were operating counter to farmers’ interests and corruptly siphoning off fees and commissions, both the (now opposition) Congress party and the farmers’ unions agreed with them.

So we come back to where we started. The farm bills will give farmers everywhere in India the right to break free from the mandis and sell their produce to whoever they want all across India. The inevitable consequence of this reform will be to drive investment into the infrastructure for getting goods to market and the storage capacity.

Currently, the United Nations FAO states that 40 per cent of food produced in India is wasted. The legislation establishes a framework for commercial agreements with farmers who will be guaranteed a price under contract and paid promptly – unlike the APMCs – and the decision over what to plant will be taken by the farmer on his own land.

If all this is so beneficial, then why are so many farmers protesting? The answer is that once it is legal for a farmer in Bihar to sell his crop in Punjab, then the bloated subsidies milked by the controllers of the APMCs for so long will be undercut.

State politicians cannot afford to subsidise the whole of Indian farming and so the top-ups will be slashed. Punjab farmers who have accepted the corruption of the system as the price they have had to pay for the subsidies that inflate their returns fear they will see their revenues return to market levels.

The MPs who spoke out so fiercely about the poor farmers of India who are being unjustly treated should rethink their narrative. The farmers of India have been ripped off for far too long. The government of India is trying to give them the same freedoms over their land and their produce that any MP in the UK would insist are their constituents’ basic human rights.

David Beckham wearing a David Austin Roses "King's Rose" speaks with King Charles III during a visit to the RHS Chelsea Flower Show at Royal Hospital Chelsea on May 20, 2025Getty Images

David Beckham wearing a David Austin Roses "King's Rose" speaks with King Charles III during a visit to the RHS Chelsea Flower Show at Royal Hospital Chelsea on May 20, 2025Getty Images

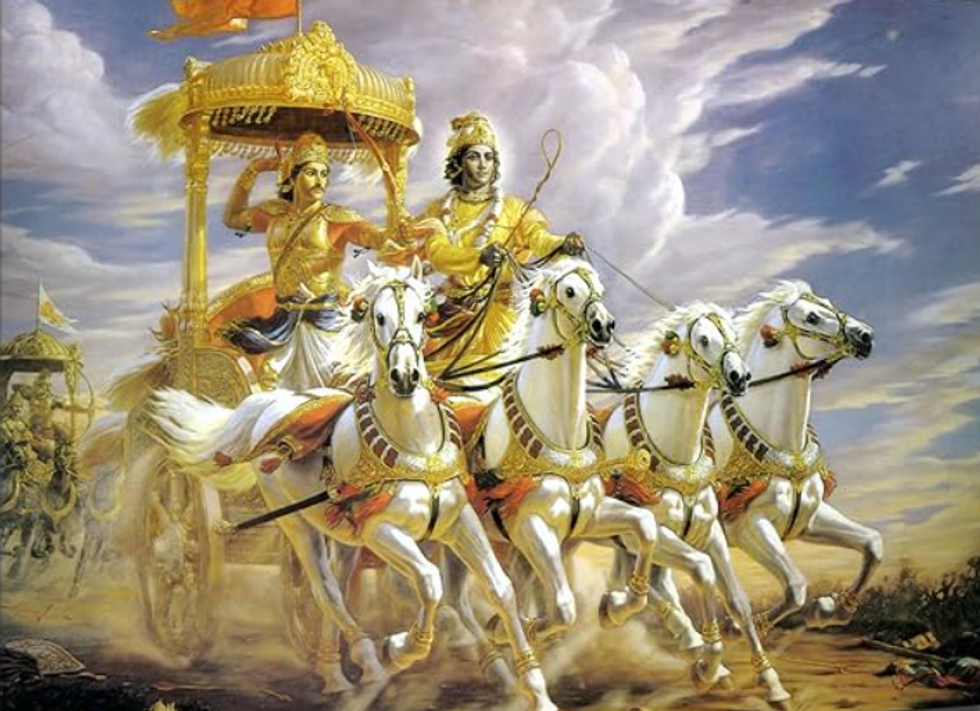

Kurukshetra battlefield illustration

Kurukshetra battlefield illustration

Chanakya

Chanakya  Shimla Agreement

Shimla Agreement Kargil War 1999

Kargil War 1999

Vivid depiction of the Kurukshetra battlefield, showcasing Arjuna and Krishna in the chariot amidst the chaos of warAmazon

Vivid depiction of the Kurukshetra battlefield, showcasing Arjuna and Krishna in the chariot amidst the chaos of warAmazon

UK MPs ‘should rethink support for India farmers’