by Amit Roy

FAMILY AND FRIENDS PAY TRIBUTE TO A SCIENCE ICON

AT STEPHEN HAWKING’S memorial service at Westminster Abbey last Friday (15), we were all reminded Britain has a long and glorious history of scientific achievement.

Distant memories of my A level physics kept floating by as I listened to the Dean of Westminster, the Very Rev Dr John Hall, lead the service.

“We come to celebrate the life of Stephen Hawking in this holy place where God has been worshipped for over a thousand years and where kings and queens and the great men and women of our national history are memorialised,” he began. “We shall bury his mortal remains with those of his fellow scientists.

“Hawking’s grave will be besides that of Isaac Newton, buried here eight days after his death in 1727, and near the graves of John Herschel, buried here in 1871, Charles Darwin in 1882, Ernest Rutherford in 1937, and John Joseph Thompson in 1940.

“Nearby are memorials to other distinguished scientists, including Paul Dirac, at whose memorial dedication here in 1995 Prof Hawking gave the address.”

Close by is also the grave of the mathematician James Clark Maxwell and memorials for the penicillin pioneer Howard Walter Florey and the physicist Michael Faraday, master of electricity.

Ah, Newton, I once knew him well – or, at least, his laws of motion. If you push against a wall, it will push back at you with an “equal and opposite” force.

As for Darwin, I can never quite remember the full name of the book that he published on November 24, 1859 is: On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.

At Christ’s College, Cambridge, there is a statue of Darwin, not showing him with his familiar full beard, but as a young man. His old room in First Court is preserved as though he was still there as an undergraduate.

At the Westminster Abbey service, tributes were paid to Hawking by his close friend of many years, Lord Martin Rees, the Astronomer Royal, who said: “His name will live in the annals of science. Nobody else since Einstein has done more to deepen our understanding of space and time.”

Nobel Laureate Kip Thorne, who had collaborated with Hawking, added: “You remember Newton for answers, you remember Hawking for questions.” Hawking died, aged 76, in Cambridge on March 14. His ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey in a simple ceremony.

The memorial stone reads: “Here lies what was mortal of Stephen Hawking 1942-2018.”

Inscribed on the tablet is arguably his most famous equation describing the entropy of black holes.

Afterwards, Hawking’s voice was beamed into space towards the nearest black hole. It was set to an original piece of music by Vangelis, the Greek composer who created the soundtrack for the 1981 film Chariots of Fire.

Hawking’s 47-year-old daughter, Lucy, explained: “It is a message of peace and hope, about unity and the need for us to live together in harmony on this planet".

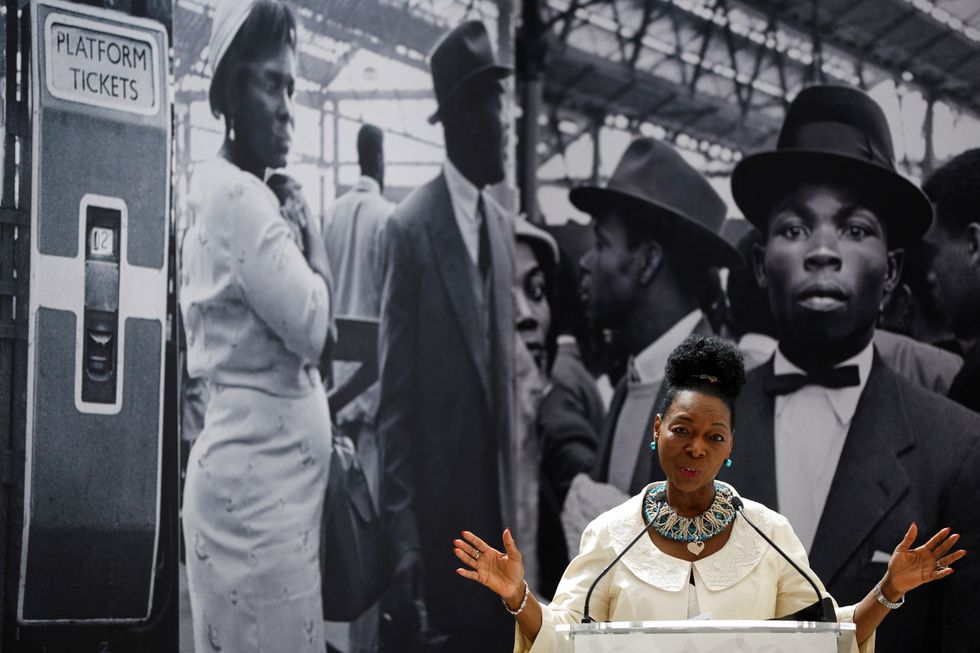

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

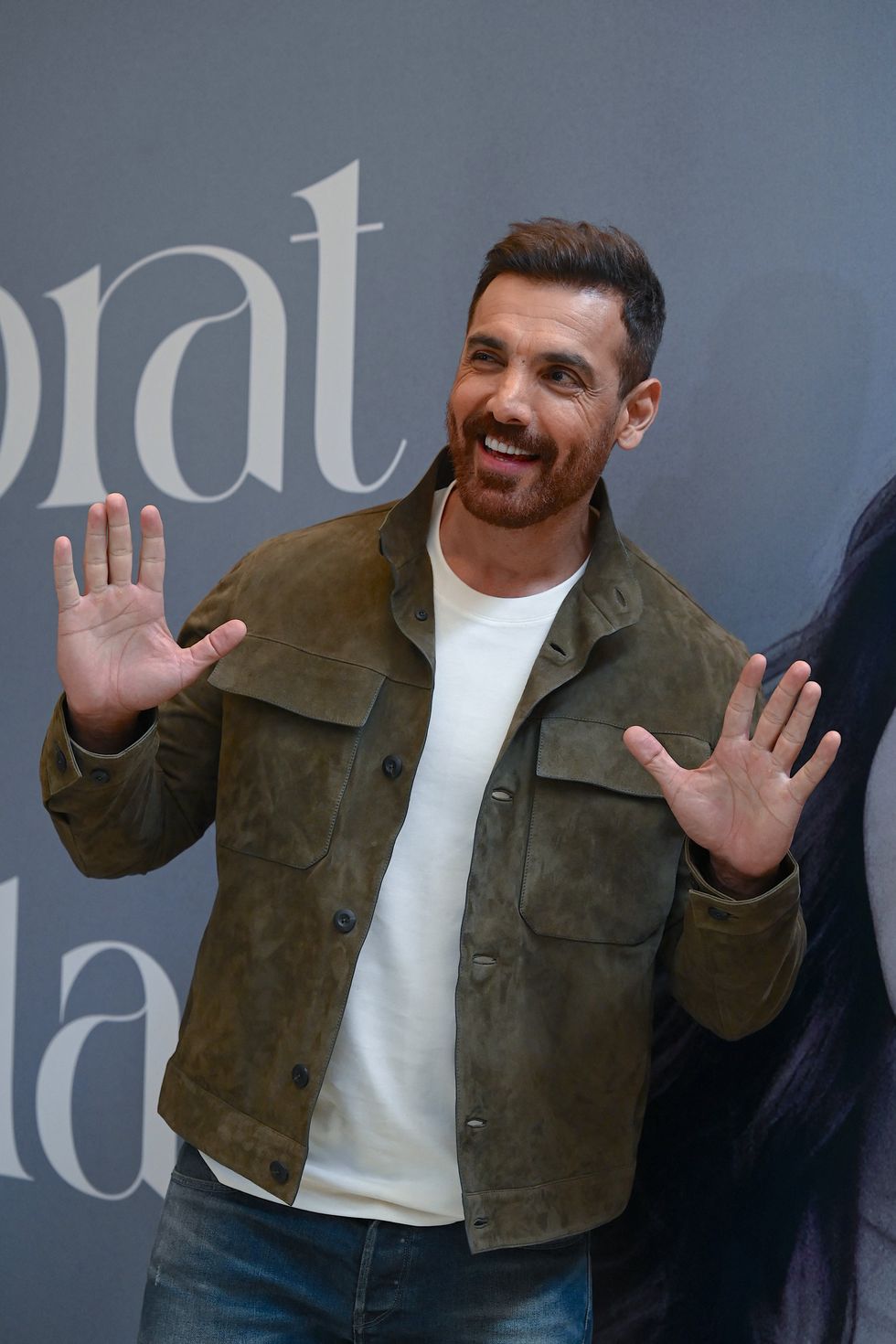

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf

Shraddha Jain

Shraddha Jain Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf

William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta

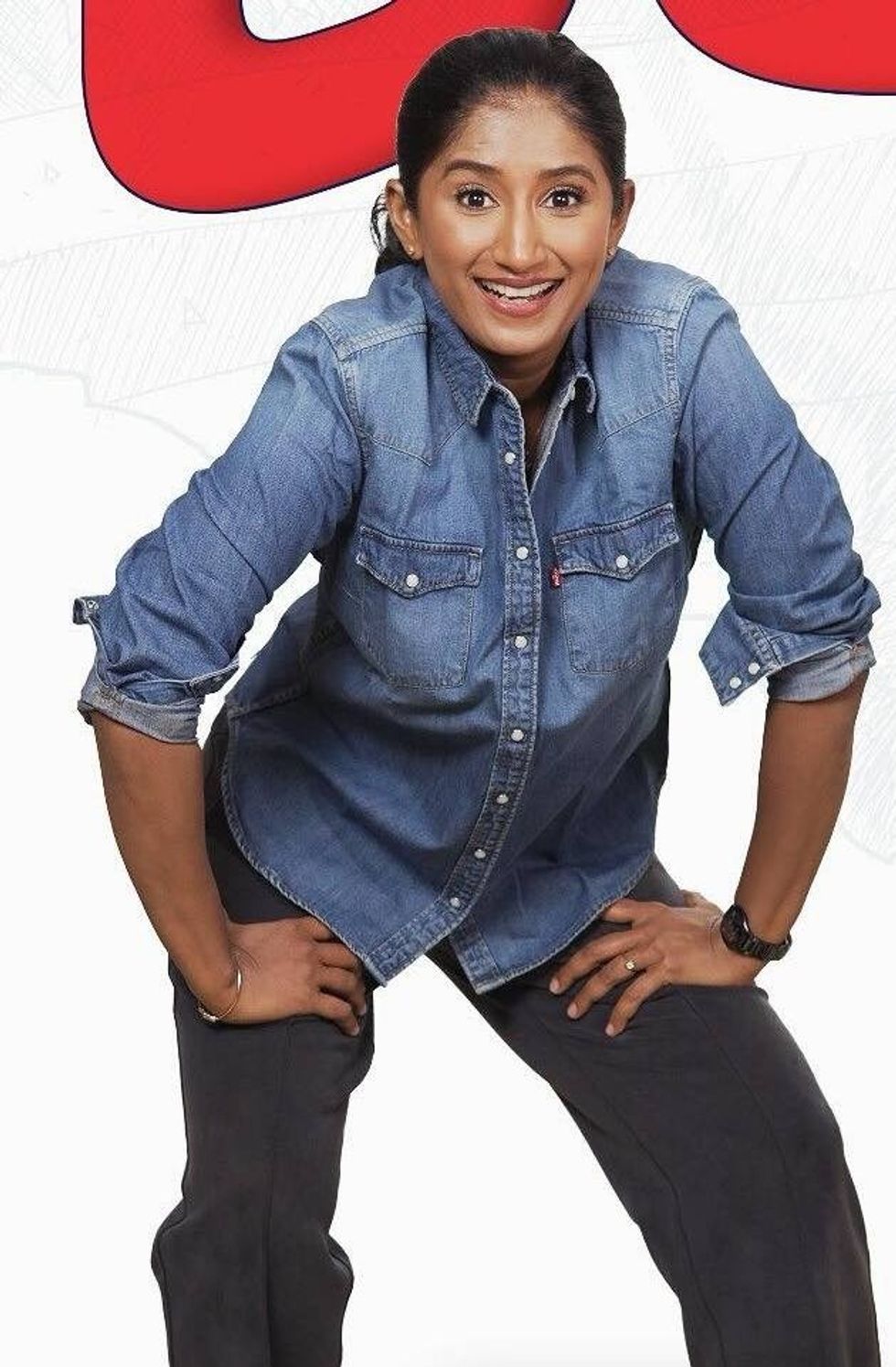

Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta Money Back Guarantee

Money Back Guarantee Homebound

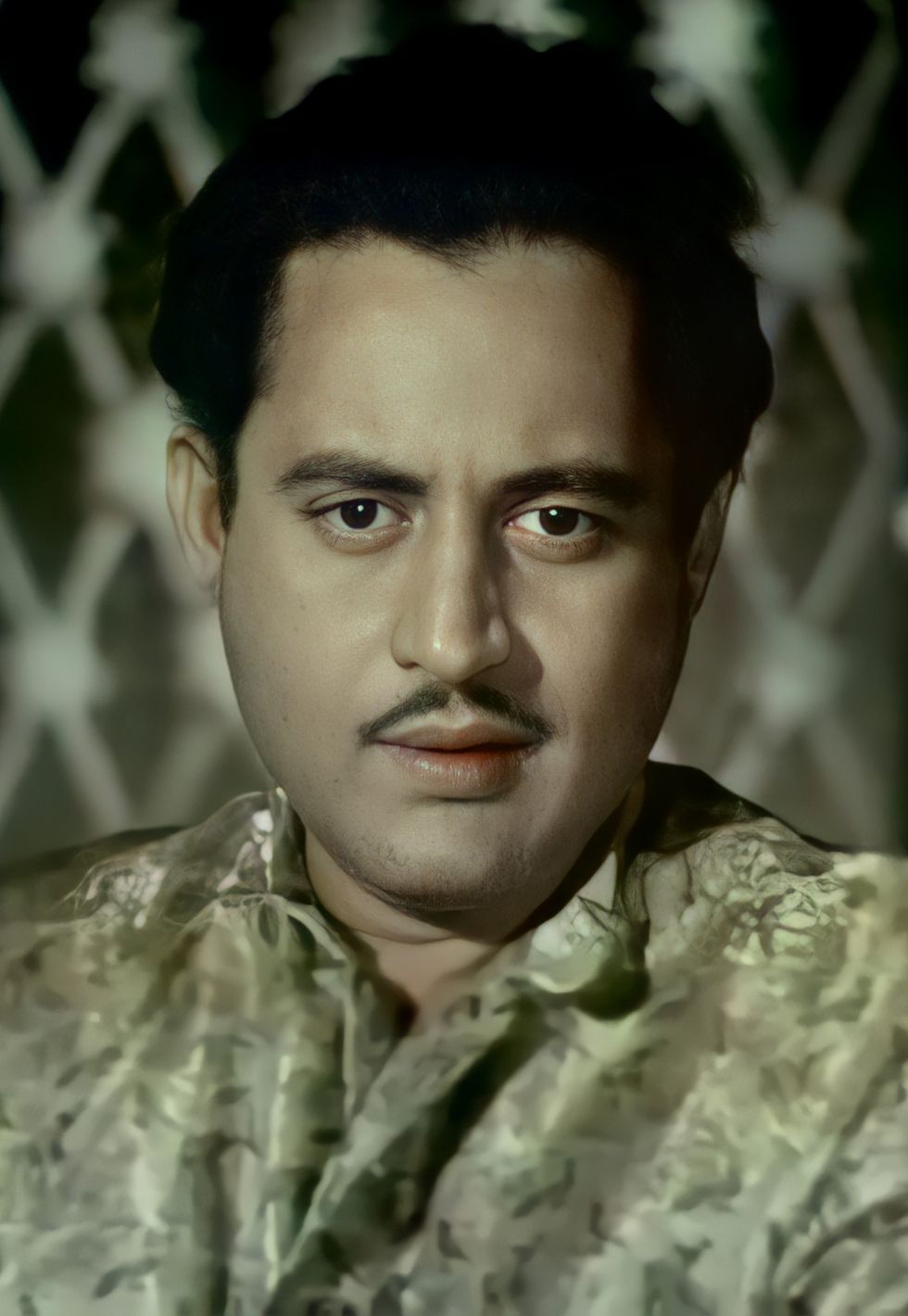

Homebound Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand

Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand Sarita Choudhury

Sarita Choudhury Detective Sherdi

Detective Sherdi

Police may probe anti-Israel comments at Glastonbury