SOUTH Asian women are the least likely to check their breasts for signs of cancer, new research revealed this week.

Around 40 per cent never check their breasts at all, compared to 27 per cent of black women and 13 per cent for other ethnicities, according to the Estée Lauder Companies (ELC) UK & Ireland’s 2021 Breast Cancer Campaign.

The analysis also found a third of south Asian women said they do not know what to look for or forget to carry out the checks on their own. More than one in 20 (7 per cent) don’t feel comfortable checking themselves due to cultural reasons.

Kreena Dhiman, who was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2013, said she was unsurprised by the statistics. “If I consider my own circumstance, I never self-checked,” Dhiman told Eastern Eye. “Conversations around our bodies simply don’t happen within our community and, as a result, knowledge on subjects such as breast health is almost non-existent.”

Dhiman said there are several factors at play, including cultural implications that create difficulties when discussing your body. “As a Hindu, from a young age we are told that when on your period you are ‘unclean’ or ‘impure’ and unable to go close to any places of worship or religious events,” explained Dhiman. “That conditions us to believe that there is something wrong with the way our bodies function, it creates barriers and builds walls when it comes to the female body.”

She believes that the immigrant history of south Asians in the UK may create difficulties too. Many of the community have arrived in the UK because of immigration and have endured great struggles, Dhiman explained.

“Incredibly, the south Asian community came through that struggle, and many have

gone on to raise a generation of highly driven, highly successful and well-educated

children,” she said, “but those children have seen the adversity their elders have faced, they carry an element of responsibility, a desire to protect and repay their elders.

“It’s those children, my generation, who find it difficult to display vulnerability, because we have raised to be strong, to be successful, to achieve. Ill health stands to get in the way of that, so it’s far easier to ignore the warning signs.”

Research also showed that south Asian women believe there is a stigma in their community around speaking about breast cancer as it is not openly discussed.

Dhiman agreed with the findings, commenting that stigma is “rife” among some

members of the Asian community. When women are introduced to prospective suitors for marriage, Dhiman said cancer could ruin a potential match. “It can be a real block in the road where those suffering are perceived to be damaged goods,” she said. “It’s those stereotypes that needed to be broken.”

Dr Zoe Williams, GP and broadcaster, said breast health should be a part of our self-care routines alike to brushing your teeth. “There’s no shame, breasts are part of our bodies,” she explained. “It’s our responsibility to take care of them. Regular checking is vital, ideally once a month, but remember checking your breasts is a skill and like any other skill it takes practice to get good at it.”

She advised women to look out for several different signs – not just lumps. Symptoms can include irritation or dimpling of the skin on the breast or flaky skin in the nipple area, for instance. Dhiman’s first symptom was an inverted nipple.

“If you notice any unusual changes, it’s important to contact your GP as soon as possible,” Williams said.

Dhiman said her message to Eastern Eye readers would be that the problem will not go away if they simply ignore it. “This isn’t something that we can hide away from,” she said. “Breast cancer is real, and the lack of awareness in our community means that it’s often detected later than our western peers.

“That ultimately means that we will lose proportionately more lives to the disease, and that needs to change.”

Additional key findings revealed that 82 per cent of black, south Asian and LGBTQIA+ women believe there needs to be better access to tools and resources that feature a more diverse range of people to highlight that breast cancer can affect every body.

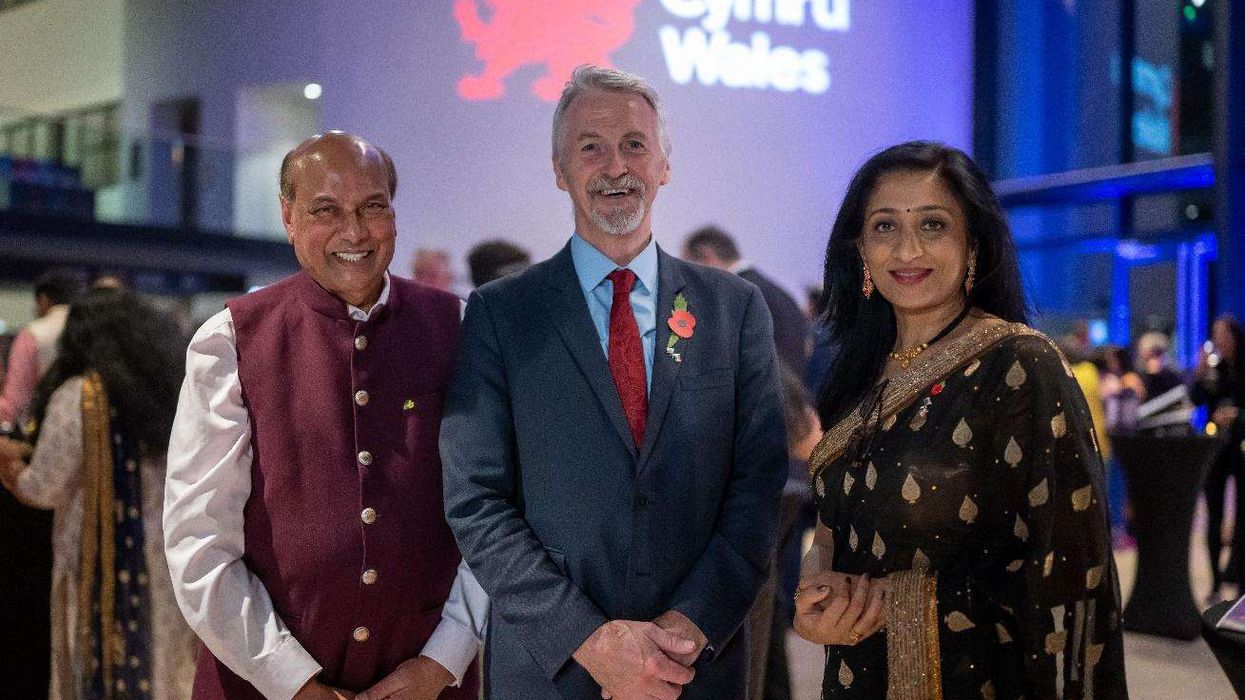

David Lammy

David Lammy Seema Malhotra

Seema Malhotra Moments from the event

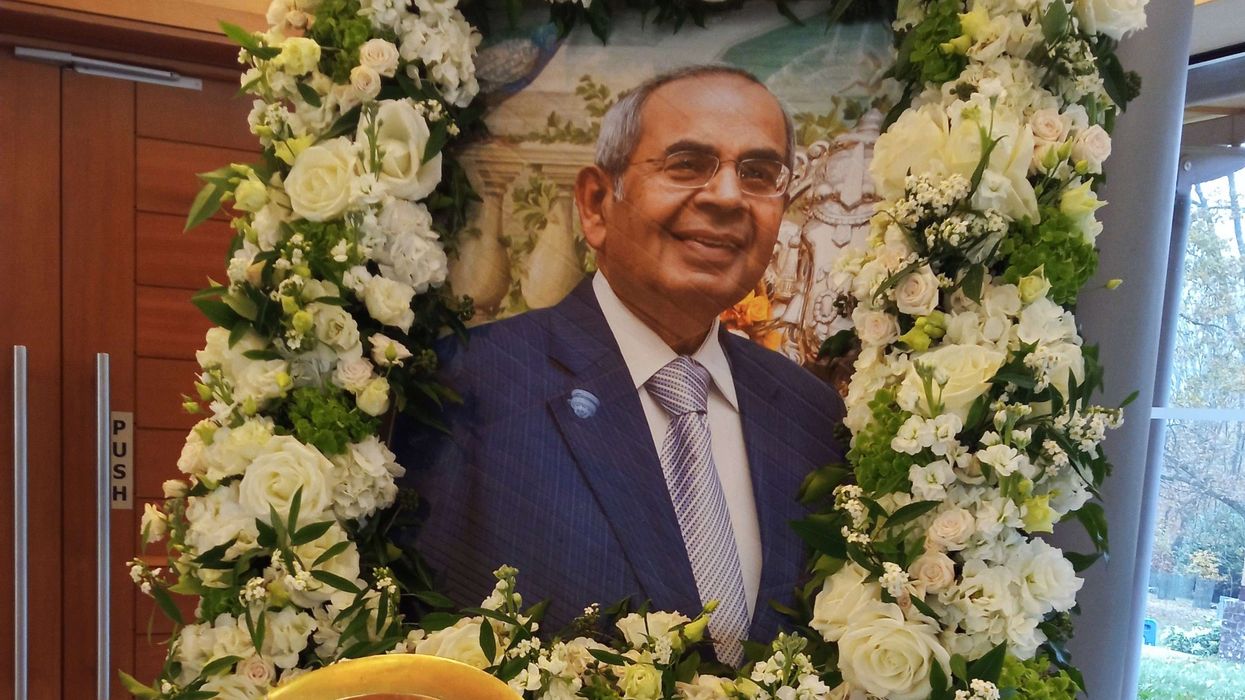

Moments from the event