by AMIT ROY

WHAT happened in Sri Lanka on Easter Sunday is utterly alien to the culture of the island.

To get some sort of understanding of the massacre, in which at least 321 people were killed and 500 injured in coordinated attacks on three churches and three hotels, one needs to go back to the epic, the Ramayana. This sets out the rules of engagement, not only in India, Sri Lanka and Nepal, but across much of south Asia.

Ravana, the demon king of Lanka who has kidnapped Prince Rama’s wife, Sita, is the villain of the Ramayana. The epic has had a considerable influence in shaping the culture of the region. Ravana, who is depicted with 10 heads and 20 arms to signify his strength, is ultimately defeated and killed by Rama. The latter crosses into Lanka across a narrow strip of sea from India, accompanied by an army of monkeys.

But even Ravana, a great scholar who played the veena well and was an able administrator, had his virtues, which is more than can be said

for the group which carried out the suicide bomb attacks on the island’s Christian community. That it was targeted when the victims were at prayer transgresses all the cultural values set out in the Ramayana.

When I first went to Sri Lanka, the conflict was between the Tamil Tigers and the Sinhala-dominated army. According to the 2011 census, Buddhists made up 70.2 per cent of Sri Lanka’s population (now estimated to be 21 million); Hindus 12.6 per cent; Muslims 9.7 per cent; and Christians, who are mainly Catholic, 7.4 per cent.

The use of suicide bombers should make it easier for the Sri Lankan government to track down those responsible. But beyond that, can anything be done to protect the vulnerable Christian communities, not only in Sri Lanka, but also in the Middle East, Pakistan (where the blasphemy laws present a particular problem as witnessed in the case of Asia Bibi), Egypt, India and other countries?

From my experience of Christians in India, they have done only good through the running of excellent schools, for example.

In Britain, the government has announced it will act in defence of Christians. It estimates that 215 million Christians worldwide face persecution and that 250 are killed every month.

Theresa May’s Easter message, even though the prime minister did not have Sri Lanka in mind, was uncannily prescient: “Churches have been attacked. Christians murdered. Families forced to flee their homes. That is why the government has launched a global review into the persecution of Christians. We must stand up for the rights of everyone, no matter what their religion, to practise their faith in peace.”

That privilege must not be abused in Britain.

After the carnage, May – like heads of government all over the world – expressed her horror at the “appalling” violence which has returned to Sri Lanka after a relatively peaceful decade.

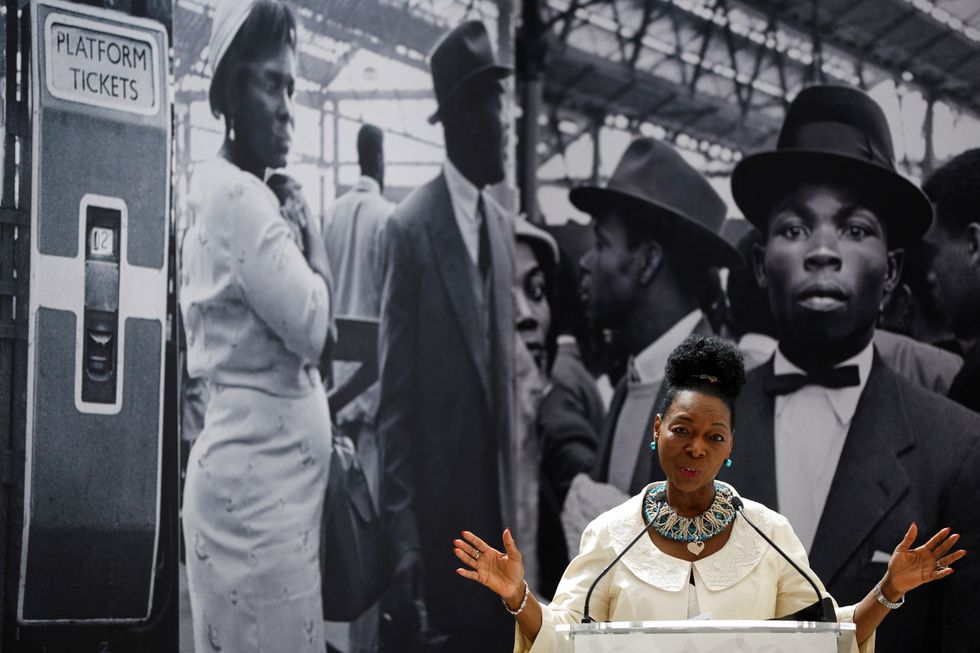

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 22: Baroness Floella Benjamin speaks during the unveiling of the National Windrush Monument at Waterloo Station on June 22, 2022 in London, England. The photograph in the background is by Howard Grey. (Photo by John Sibley - WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh

Ed Sheeran and Arijit Singh Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’

Aziz Ansari’s Hollywood comedy ‘Good Fortune’ Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’

Punjabi cinema’s power-packed star cast returns in ‘Sarbala Ji’ Mahira Khan

Mahira Khan ‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience

‘Housefull 5’ proves Bollywood is trolling its own audience Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’

Brilliant indie film ‘Chidiya’  John Abraham

John Abraham Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal

Hina Khan and her long-term partner Rocky Jaiswal  Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut

Shanaya Kapoor's troubled debut Sana Yousuf

Sana Yousuf

Nigel Farage and Zia Yusuf

Nigel Farage and Zia Yusuf