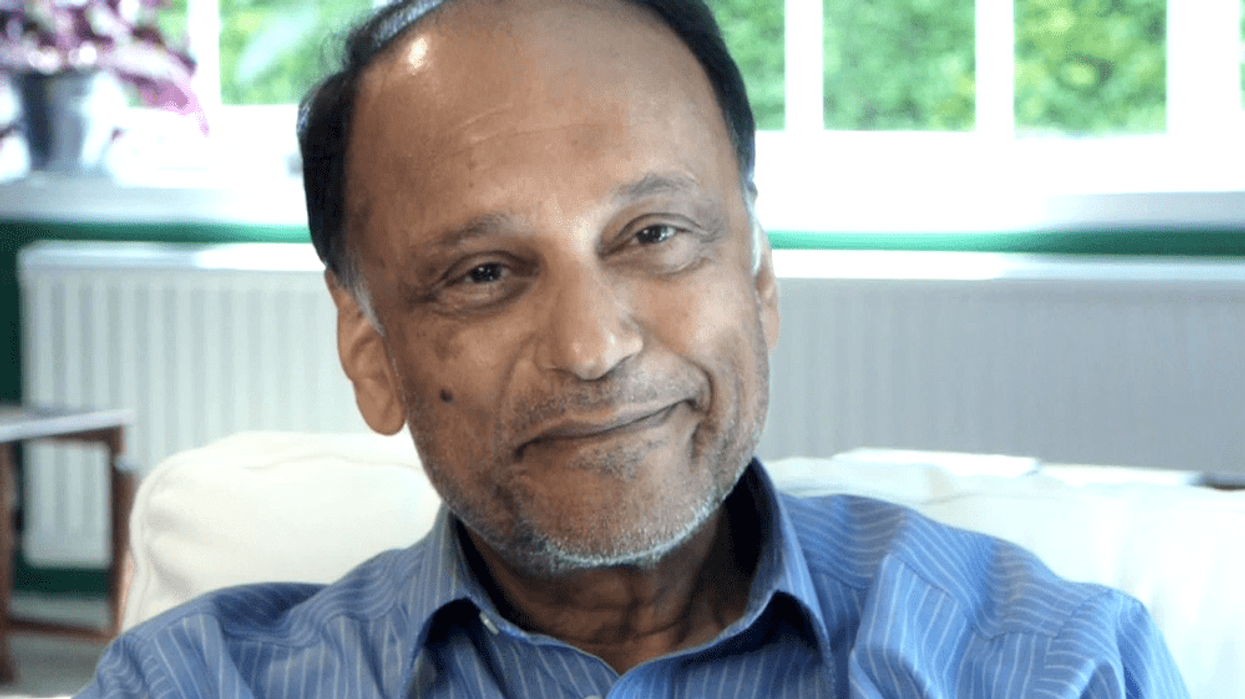

PROF Sir Partha Dasgupta is the world renowned Cambridge economist whose landmark review, The Economics of Biodiversity, was launched in London at the Royal Society on February 2, 2021.

Since publication a year ago, the review’s findings have been pretty much accepted worldwide. It argues that when it comes to building everything from roads to dams, governments should take into account any damage to the environment as an integral part of the planning process.

Dasgupta sums up his message, which has been welcomed by everyone from Prince Charles to Sir David Attenborough: “Put simply: without nature, there would be no life. The economics of biodiversity is therefore the economics of nature. But nature’s resilience is being severely eroded, with biodiversity declining faster than at any time in human history.”

At the rate in which nature is being degraded, “we would require 1.6 earths to maintain the world’s current living standards”.

He says: “I have one very important recommendation, which is we now need a global Marshall Plan for nature – like the Marshall Plan post Second World War to revive European economies.”

Nature is so important that Dasgupta thinks it should be taught to school children from the earliest age: “In fact, the review is ending with a plea to have nature studies as part of the permanent education of our children – from the beginning, absolutely. It should be compulsory, like how languages have to be compulsory.”

Dasgupta feels very strongly on the subject. He has been combining the study of economics with ecology for the last 30 years. Back in March 2019, when the then chancellor Philip Hammond was looking for someone to conduct an independent review of global biodiversity, Dasgupta was pretty much the obvious choice.

The treasury published his “interim” review on May 1, 2020, and the full 610-page report in February 2021. “I was not so much interested in influencing the treasury as much as influencing the concerned citizen,” he says, stressing, “My reader is the concerned citizen.”

But his review has certainly been taken very seriously by his peers and by experts.

Joseph E Stiglitz, the Columbia University professor who won the 2001 Nobel Prize for economics, called Dasgupta the “world’s leading economist on ecology, economics, and growth and development”.

Prince Charles agreed with Dasgupta’s warnings: “It is sheer madness to continue on this path. Sir Partha Dasgupta’s seminal review is a call to action that we must heed, for it falls on our watch and we must not fail.”

Attenborough, whose TV documentaries have influenced, especially, young people all over the world, also welcomed this “comprehensive and immensely important report” and says that “the Dasgupta Review at last puts biodiversity at its core and provides the compass that we urgently need.

In doing so, it shows us how, by bringing economics and ecology together, we can help save the natural world at what may be the last minute – and in doing so, save ourselves.”

Dame Fiona Reynolds, a former director general of the National Trust and now Master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, says: “The Dasgupta Review offers hope for nature across the planet by showing us how we need to think and what we need to do differently so that we live within nature’s limits, not beyond them.”

Lord Nicholas Stern, IG Patel Professor of Economics and Government at the London School of Economics, who himself published a far-reaching report on climate change in 2006, adds his support: “It provides the foundation for urgent action needed now to tackle the interconnected challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss.”

The review is critically important for prime minister Boris Johnson, who co-hosted the COP26 climate change conference in Glasgow in November 2021 with Alok Sharma as president: “I welcome Professor Dasgupta’s review, which makes clear that protecting and enhancing nature needs more than good intentions – it requires concerted, co-ordinated action.”

In a sense, Dasgupta was born into economics, studied economics and married into economics. He was born in Dacca (now Dhaka) in pre-partition India on November 17, 1942 and grew up as a child in India and the US. His father, Amiya Kumar Dasgupta, who has been hailed by Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen as “one of the founding fathers of modern economics in India”, greatly influenced his son. “My father was a real scholar,” says Dasgupta. “What I learned from my father was to think logically based on evidence…He was truly an intellectual.”

After a first degree in Delhi, Dasgupta was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1962, to read physics, but later switched to economics and completed his PhD in 1968. That was the year he married Carol, the daughter of James Meade, who would win the 1977 Nobel Prize for economics.

After happy years at the London School of Economics and a stint at Stanford University in wood trees, the Santa Cruz mountains and the Pacific Ocean – Dasgupta returned to Cambridge in 1985 as professor of economics. He was knighted in 2002. “I retired at the end of 2010,” he recalls. “We have a 67-year-old retirement thing. I have published books and I’m still a fellow of St John’s College and I’m an (Frank Ramsay) emeritus professor. I’m very active. The only thing I don’t do is teach and I don’t have to examine either.”

In his review, Dasgupta has said that the influence of his father, among others, “on the way I frame economics has become increasingly evident to me”. He has added: “Above all, I am grateful to Carol Dasgupta, on whom I have tested pretty much every idea in the review. Her suggestions on what to emphasise and what is superficial have been invaluable.”

He has spoken of their first encounter: “When I was shifting from mathematics to economics, I met my wife. I knew she was the one for me the first time we met, and I asked her to marry me on our second date. It was 1968 when she graduated and I finished my PhD, and that’s when we married.”

Although Dasgupta is the author of the review, he was helped by a team organised by the treasury. “I have a team of 12 or 13 people, seconded from various ministries and I have one from the Bank of England. I have a very nice advisory panel of the great and good. But it’s an independent review, completely independent.”

While working on his review during lockdown, Dasgupta and his wife made it part of their routine of “doing a long walk each day”.

He says: “The review really is trying to rewrite economics. We love globalisation – fantastic stuff. For years now, we’ve been talking about globalisation, free trade, free movement of people. Many of us had been writing, without anybody noticing, opening up trade has really had a bad effect on poor people, particularly poor people in the third world, because their primary products are under-priced.

“You have forests in Malaysia, you cut the forest down because you’re exporting the timber to China or to Europe. But what about the fact that deforestation is causing landslides? Downstream farmers and fishermen are being affected. They’re losing income. But that loss is not being included in the price of the timber.”

His argument is Gross Domestic Product is not the only measure of human progress. “So at the moment nature is like a bandage. The treasury and the Bank of England don’t have nature in any of their models. Absolutely none at all.”

“There is a momentum of economics, which the treasuries all over the world and planning commissions have, in which nature is a footnote. (They say,) ‘What we need are infrastructure, roads, buildings, and so forth,’ which we do absolutely. But there is a cost and a benefit coming from nature. And if that is not an essential part of your calculation, then it’s doing economics without human beings in it.”

His review reveals there is a downside to dams. “There are about 40,000 high dams in the world today. And it’s one of the favourite things for developing planners... Nobody actually ever looked at the ecological impact of dams. Whereas, in fact, dams are terrible for nature because it fragments river systems. So fish can’t spawn.

“Typically, when protests are made about dams nowadays, they talk about ecology a little bit, but usually it is about displaced people. It’s in terms of what happens to the people who are living there...notice the language you’re using – it has nothing to do with nature.”

His review was published just six days before a Himalayan glacier broke away, triggering a flood that swept away everything in its wake, including the Rishiganga hydroelectric dam and damaging another on the Dhauliganga River in the Indian state of Uttarakhand.

Dasgupta’s immediate reaction was: “I cannot comment on individual dams, but high dams, as a general rule, have proved to be bad investment even when one ignores environmental imperatives. That means that as a general rule they are even worse if the risks they add to people’s lives are taken into account.”

The review states: “Biodiversity loss is also intimately related to climate change. Indeed, climate change may become the major driver of biodiversity loss in the coming decades.”

It goes on: “Land use change has been identified as the leading driver of recently-emerging infectious diseases. Deforestation, conversion of primary forest for intensive agriculture and extractive industries such as logging, mining and plantations, and illegal wildlife trade are causing both biodiversity loss and contributing to the emergence and spread of infectious diseases. One important factor is increasing contact among people and wildlife that carry zoonotic pathogens. This leads to ‘spill-over infections.’... The havoc that Covid-19 is causing underscores the importance of biodiversity for our health and that of the global economy, and ultimately the need for the human enterprise to live within the ‘safe operating space’ of the biosphere.”

Dasgupta began his review a year before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. He cannot be sure, of course, that the cause of the pandemic was through people eating the meat of wild animals. “It wasn’t as though we’ve invented Covid-19. This virus has been around. It was sitting out there in animals. And now we’ve caught this. That’s our problem. Since the Industrial Revolution that’s 250 years, but in evolutionary time, that’s zero. We shouldn’t mess around with things that we don’t know so well.”