Hazra Begum has been living in fear since witnessing men chanting Hindu religious slogans hack, bludgeon and burn Muslims to death in Delhi's worst sectarian riots in decades.

Ten days after the violence, she is among 1,000 people at a squalid relief camp too scared to go home, wondering if the mixed Hindu-Muslim areas where the violence took place will ever recover.

"I can't trust anyone now," she told said as she sobbed at the makeshift camp in an open prayer ground in the Mustafabad area of the Indian capital that was the epicentre of the unrest.

"I will never forget how these men wearing helmets and chanting Jai Shree Ram (Hail Lord Ram) shouted 'kill the Muslims, don't spare any of them.'"

At least 50 people died in the riots on February 24-25, over two-thirds of them from India's 200-million-strong Muslim minority, according to hospital lists. One policeman was also killed.

Critics blame prime minister Narendra Modi and his Hindu nationalist ruling party for stirring animosity between communities that have co-existed largely peacefully for decades.

Modi, 69, who was chief minister of Gujarat state in 2002 when around 1,000 people perished in religious riots, insists he wants to protect India's secular tradition.

- 'One-sided' -

For the most part, it was the Muslims who were the victims. They were shot, stabbed, beaten to death or burned in their shops and homes in rundown districts of northeast Delhi.

The government-appointed Delhi Minorities Commission said it was "one-sided and well-planned", with "maximum damage... on Muslim houses and shops with local support."

But there was violence on both sides.

In Ashok Nagar, a Hindu-dominated locality, anger was palpable as men complained how no one was highlighting their plight.

"Our homes and shops have also been burnt, our people have died as well. A Hindu (security) official was stripped and stabbed to death," said Dharam Veer.

"But no one seems to care about us. Everyone is saying only Muslims were targeted. This is not the case, as you can see."

Both sides agree, though, that the police were slow to act. Some even accuse them of helping Hindu rioters as they went on the rampage with Molotov cocktails and pouches of acid.

- All change -

Such is the fear of more violence that some Muslims, even those who do not live where the riots took place, are changing their habits, their appearance and even their names.

"There seems little hope (of things getting better). Things have only gone downhill since 2014," when Modi was first elected, said a 26-year-old journalist who asked not to be named.

"From lynchings to rioting, the minorities, particularly Muslims, are being persecuted with impunity. The hate has entered our households."

Student Salim, 23, said that he has changed his name on apps for ride-sharing services Ola and Uber to make it sound less Muslim to avoid arguments or even violence.

"I am more conscious about being a Muslim now than I was five years ago," he said.

"I'll leave this country when I get the opportunity. I know that Muslims are not safe anywhere in the world but living here has just become humiliating."

Recent graduate Noor, 27, said that her mother had decided not to wear the Islamic burqa on an upcoming trip out of town.

"This is a woman who never shied away from wearing the burqa. She used to wear it during our school parent-teacher meetings... the fear now is something else," she said.

Reports said men were being made to drop their trousers to prove their religion since Muslims are often circumcised but Hindus are not.

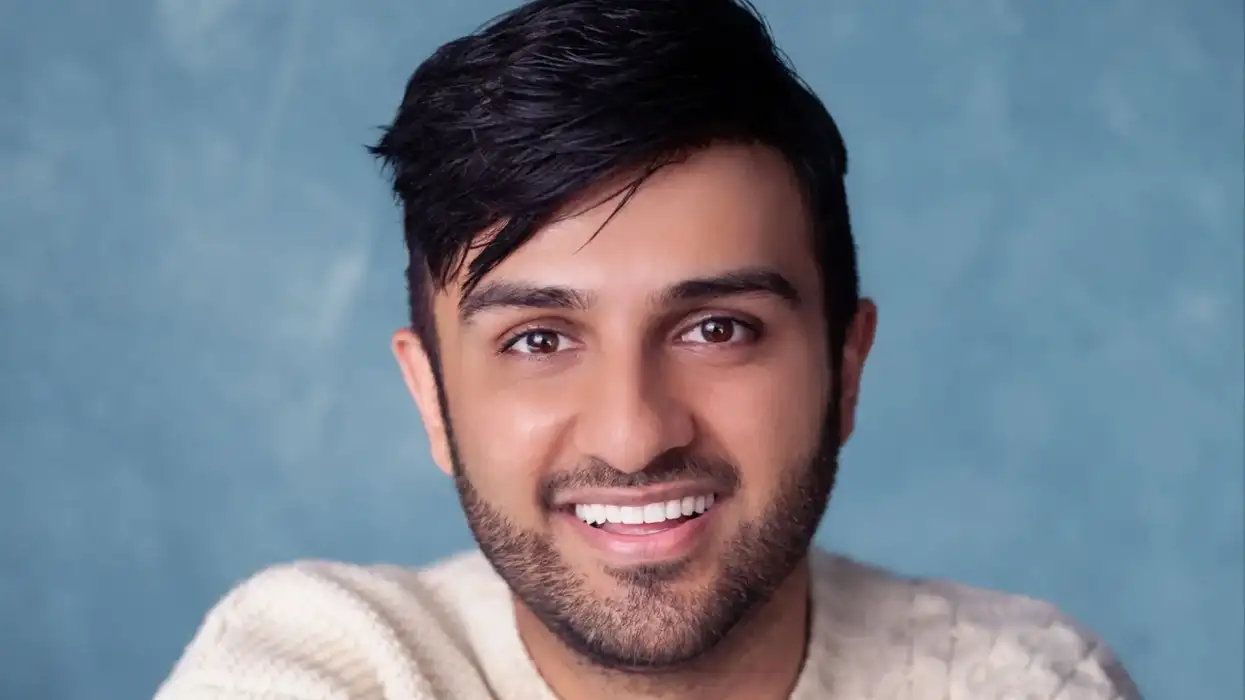

Farhan Zaidi, 30, a marketing professional, said he was considering shaving off his beard and he and his friends now use Hindu-sounding names in public.

"The problem with Muslim men is that your identity is in your pants," he said. "In reality, if I am caught, then there is no escape."