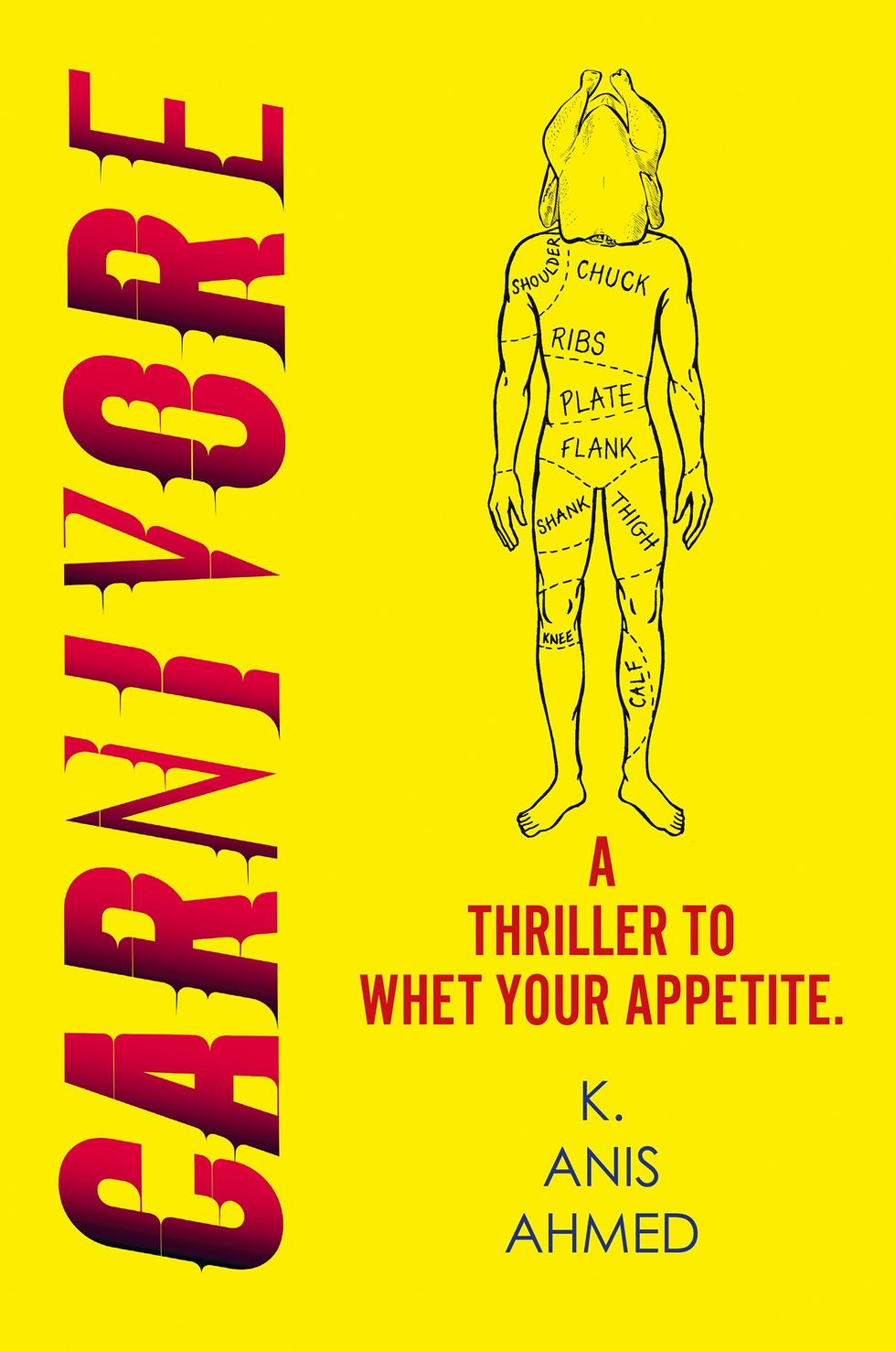

From the blood-soaked backstreets of Dhaka to the polished kitchens of Manhattan’s elite, K Anis Ahmed’s new novel Carnivore is as imaginative as it is provocative. A satirical thriller steeped in class tension, culinary obsession and primal survival, Carnivore follows Kash, a Bangladeshi immigrant-turned-chef who launches a high-end restaurant serving exotic meats – only to become embroiled in a sinister world of appetite and ambition.

But this is no simple tale of knives and recipes. Ahmed – a seasoned journalist, publisher, and president of PEN Bangladesh – brings a sharp eye to the grotesqueries of power and privilege. In this exclusive interview with Eastern Eye, he speaks about his passion for food, the moral murkiness of his characters, and why even the most ordinary people can spiral into extraordinary darkness.

What first connected you to writing?

I have been an avid reader since childhood – starting with Bengali and Russian fairy tales, before moving on to Enid Blyton and Agatha Christie. In my teens, I discovered Somerset Maugham and Graham Greene. Their travel writing sparked my imagination. The idea of being a wanderer through the world as a writer captivated me and pulled me toward writing as a vocation.

What inspired your new novel Carnivore?

I lived in New York for a time and love the city. I have always had a strong interest in food and found the idea of running a café, bar or restaurant quite enticing. Since I could not do it in real life, I created one in fiction – and let it go in some wild directions.

Tell us a little about the story.

It is about a young immigrant, Kash, who runs a wild game restaurant in downtown Manhattan. When the 2008 financial crash hits, his investors and clientele disappear. To stay afloat, he turns to hosting private dinners for the super-rich. In chasing a gig for a secretive billionaire’s dining club – while also dealing with a Russian money-lender – things soon spiral out of control.

What drew you to the culinary aspect?

It came from my passion for food and cooking. But cooking, for me, is more than just food – it is about identity, values and cultural expression.

As a writer, how do you develop the darker elements in a story like this?

It usually begins with a simple ‘what if’. I ask myself: how far could a seemingly ordinary person be pushed, given enough pressure or temptation? And who might they take down with them?

What inspired the title?

It was suggested by my brilliant agent, Charlie Campbell. The title captures not just the wild game theme, but also the broader idea of appetite – its excesses, its destructive potential.

What was the biggest challenge in writing the book?

Making the ultimate meal they plan feel believable – both to Kash and his team, and to the clients. None of these characters are inherently sociopathic. I wanted to explore the extremes that ordinary people might reach when driven by circumstance.

What is your favourite part of the book?

There is an episode where they go “hunting” for a peacock – I really enjoyed writing that. The backstory draws from my own memories of Eid-ul-Azha in Dhaka, where animal sacrifices take place in driveways and courtyards. It is surreal to see such rituals on such a scale in a modern city.

Who are you hoping the novel resonates with?

Anyone who enjoys a gripping story with a diverse cast and unexpected twists. It is for fans of crime thrillers, but also for general fiction readers who like discovering new subcultures – and morally daring propositions.

What do you enjoy reading, and do you have a favourite author?

I read a lot – both fiction and non-fiction, from science to history. The novel is my greatest love, and my favourite authors span classics and contemporaries. Some recent writers I have particularly enjoyed include Paul Beatty, Alejandro Zambra, Rachel Kushner and Ottessa Moshfegh.

What inspires you as a writer?

Intriguing ‘what if’ ideas, morally complex characters and the challenge of crafting sentences that feel exactly right.

What are you working on next?

I am working on a story where a seemingly normal person slowly descends into sociopathy. I want to explore how someone can unravel and become unrecognisable from who they once were.

What, in your view, makes a great novel?

A compelling premise, layered and unpredictable characters, and prose that is fresh and evocative – without being overwrought.

Why should readers pick up your new book?

Because it is a truly fun read – simple as that.

Carnivore by K Anis Ahmed is published by HarperFiction, £16.99.