WHEN Rishi Sunak became an MP, he swore his oath on a copy of the Bhagvad Gita, but few people – including perhaps Britain’s first Asian prime minister – will have been aware of the efforts of a Shropshire-born civil servant in that little moment of history.

Charles Wilkins (1749-1836) was an employee of the East India Company and an avid Sanskrit lover. He arrived in India and went on to study the language under scholars in then Benares (now Varanasi, which India’s prime minister Narendra Modi represents) and produced what is believed to be the first English translation of the holy Hindu text.

It made the Gita accessible not only to the British, but also millions of Indians, including Mahatma Gandhi, and years later, Sunak.

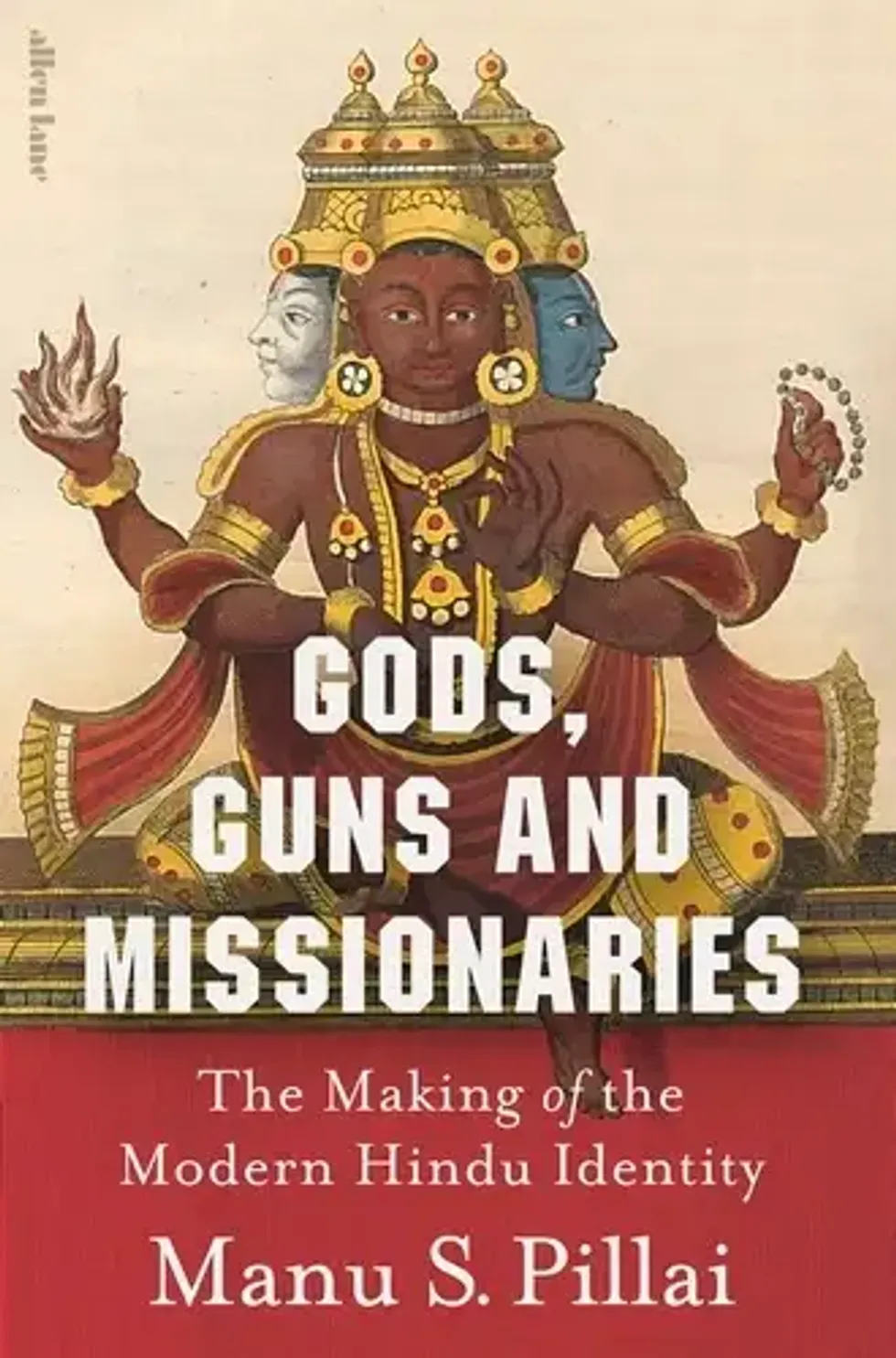

This is just one of the anecdotes Manu Pillai uncovers in his new book, Gods, Guns and Missionaries: The Making of the Modern Hindu Identity, published earlier this year.

Pillai traces the transformation of the religion over the past four centuries – from the arrival of early Europeans in the Indian subcontinent to British rulers and the rise of Indian leaders during the freedom movement – and examines the impact of those influences.

“Most of us look at Hindu identity today through the prism of Hindu-Muslim relations, because in the present, that is what became,” Pillai told Eastern Eye. “But to me, it seemed like a lot of modern Hinduism was actually influenced by colonialism and Christianity.”

Not so much in the way that missionaries converted millions of people, Pillai explained, as they “never had physical success in terms of numbers”, but “they had a lot of intellectual success in terms of placing these moulds and frameworks of thinking, which we took in order to articulate a modern avatar for Hinduism. So, I thought that story deserved to be told.”

This is his fifth book, which Pillai began in 2019, following a dissertation on Hindu nationalism at King’s College London. At the outset, he clarified the book is not about his academic thesis, rather it examines the impact of the early Portuguese, the Italians and other Europeans, then the East India Company, the British and finally, Indian reformers and politicians prior to and after independence.

Pillai said, “Hinduism is not a Western-style religion. It’s a cultural framework in which there’s multiple diversities. Think of it like a draw cabinet; it is the overall frame that is Hinduism. But each door has its own individual identity, as well.”

Pillai charts the influence of hardline Portuguese missionaries whose influence is evident in Goa even today, while in the south, an Italian priest, Roberto de Nobili, adopted the local Hindu ways in order to spread the teachings of Christianity.

The book also shows how British colonial rulers were initially reluctant to the push from missionaries in the UK to proselytise communities in the subcontinent, before eventually changing their minds. Reformers such as Serfoji and Raja Ram Mohan Roy adopted a more modern approach, followed by Dayananda Saraswati, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Jotiba Phule and Veer Savarkar, whose interpretation of Hinduism came at a time of India’s freedom struggle.

This intertwining of religion and politics is not new, though, Pillai said. History has shown how rulers patronised places of worship and this continues in contemporary times, too.

The writer described how Jawaharlal Nehru (independent India’s first prime minister) and “the Nehruvian elites made a conscious effort to keep religion out, but bubbling just beneath that first level, (but) religion was always present in politics. Caste was always present in politics.”

Pillai said, “It was Nehru’s charisma and electoral success that allowed him to keep it at bay or in check. But it was never absent. By Indira Gandhi’s time, she started playing the religious card as needed, whenever she felt her party could benefit from it.”

He added, “The difference is religion has now come much more centrestage and openly acknowledged.”

Pillai also noted how economic clout and technology have both played a part in the recent assertion of religious identity, the most obvious is the patronage of places of worship, while carrying out rituals under the guidance of a priest over a video link is now the norm.

In the book, he writes about how the spread of the English language in the subcontinent meant exposure to new ideas, thus empowering Indians to not only challenge authority, but also learn about the world outside their country.

“The British employ Indians who can speak English. They pay those Indians. Those Indians are getting cash revenue. They are no longer dependent just on their farms (to earn their living). They use that to patronise their community. They build temples,” Pillai said.

“So, ironically, the wealth created by service in the British East India Company ends up in the flowering of Hinduism. The railways, which the British laid to move their troops around, also enables pilgrim traffic to temples. “All of these things come together – technology, politics and economics.”

More recently, Pillai said Hindu resurgence “isn’t purely due to political dynamics”. His view is that with rising disposable income, “you have time to think about identity, and now you have money to patronise things.”

He cites the example of Kerala, where he is from, explain how remittances from the Gulf countries led to a boom in old family temples being renovated. “There is something culturally coded in organising a big puja, or making donations to a temple is seen as an a c h i e v e m e n t , weighing yourself in grain and donating to a temple.

“So that kind of religious identity also boomed with economic boom. It’s not as an economic boom creates some rational paradise. On the contrary, an economic boom can actually result in a greater flowering of religiosity.

“Partly because of that, post liberalisation (of India in the 1990s), there’s been a new middle class that’s emerged, there’s also now disposable income. People have the wherewithal to now think beyond roti, kapda, makaan (food, clothes and shelter), and to think about who are we as a people? And the answer to that question lies in religion, culture, heritage.”

India and south Asia’s vast diversity dictate the way Hinduism is practised, across not just the subcontinent, but also across the world, where the diaspora communities are settled. Consequently, this shapes the evolution of Hindu identity.

Pillai said the next challenge for Hinduism will be maintaining that inner diversity, “because we live in times where there’s so much emphasis on that homogenised identity, on one reading of that label, of what it means to be a Hindu.

“It takes away from how much pluralism there is within the faith itself. The richness of Indian culture, in general, has been the fact that all religions that have entered India have become pluralized, even if it’s Islam.

“Islam in Kerala is not the same as Islam in Bhopal. When the north Indian Muslims under the Muslim League, as I mention in the book, went to Kashmir in the 1940s hoping to woo the Kashmiri Muslims, they were horrified. They thought that Kashmiris, with their saint worship, and all of that were not even proper Muslims. They said, ‘we’ll have to teach them Islam first, before making them Muslims, because they couldn’t recognise that version of Islam. “Everything in India is hybridised, and in many ways, that has been our strength, these hybrid identities have continued over so many generations. “What would be a major challenge is this tendency towards homogenising… towards feeling there has to be only one version of Hinduism and one interpretation of things.

“Even our epics have so many retellings. In Kerala there is an oral kind of Ramayana, in which Shurpanakha, when she propositions Rama and says, ‘I want to marry you’. And he says, ‘No, I’m already married. You go to Lakshmana.’ Shurpanakha turns around and says, ‘That’s okay; the Sharia says you can marry twice, more than one woman.

“So this is a Ramayana in which Shurpanakha quotes the Sharia, because it’s a Muslim Ramayana.

“That is the kind of country we come from. And I think losing that, where everything has become standardised, and that’s a global phenomenon, something we’re seeing around the world. That is a tragedy. That would be the bigger challenge.

“We need more people telling these stories about our inner plural, pluralism and diversity – which is not to devalue that framework. The framework has its own value. I’m not saying that Hinduism should somehow be only about its pluralism, but at the same time, it has to be a fine balance between maintaining that inner richness, maintaining all the threads in the tapestry without painting the whole tapestry one single shade.”