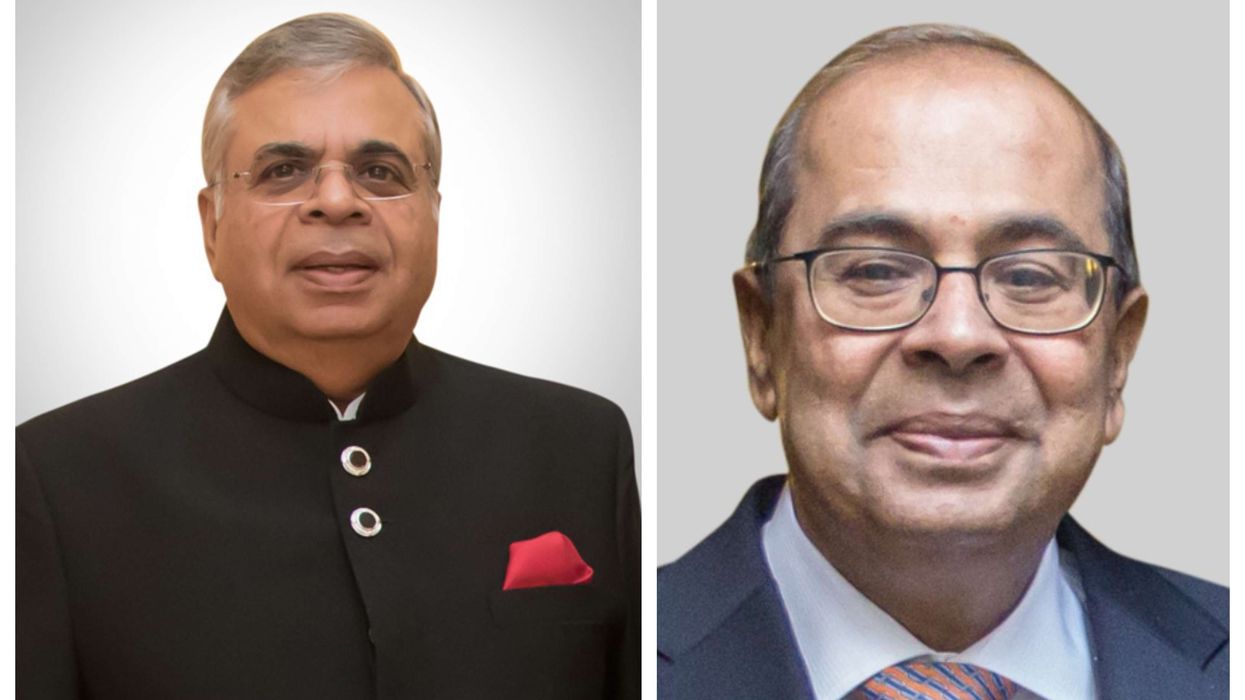

AS ONE of the most influential British Asian doctors in the UK healthcare system, Dr Kailash Chand’s career has not been short of accolades.

The medic was the first Asian to be elected as deputy chair of the British Medical Association Council (BMA) representing 150,000 doctors in the UK; has received an OBE for his services to the NHS; is a senior fellow of the BMA;

was named ‘GP of the Year’ by the Royal College of General Practitioners and has been regularly named as being among one of Britain’s top 50 most influential GPs in the annual ‘National Pulse Power List.’

Although thankful for the recognition, Chand does not wish to be known for these achievements. “I want to be known as someone who is fighting for health equalities and for the recognition of the migrant workforce within the NHS,” Chand told the GG2 Power List.

“That is what I am passionate about.”

In 2020, the battle for equality became even more significant in the wake of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic – and Chand was at the frontline. He was one of the first leaders in healthcare to highlight the disproportionate impact of coronavirus on ethnic minorities.

Last April, statistics were released regarding the number of deaths in hospital. Chand can recall seeing the high number of BAME health workers who had passed away from the virus.

“At that time, I remember seeing there were around 70 deaths (of healthcare workers) and the majority were from ethnic minority backgrounds,” he said. “That’s the first time I realised there was something terribly wrong.”

Although there were additional factors such as age, morbidities and underlying health issues, many believed that racism had an impact.

Studies showed some BAME health workers were finding it difficult to raise their concerns on the lack of PPE, in fear of a repercussions.

Chand, who was elected to the BMA board of directors last year, was extremely vocal on the issue, blaming structural racism on the impact. He appeared on several news programmes, including BBC Breakfast and Channel 4 News, to highlight the problem.

Along with several other health leaders, Chand urged government to investigate the disproportionate impact on BAME communities and the reasons behind it. Triggered by the calls to action, the government equalities office agreed to address Covid-19 health equalities in a quarterly report, of which two have been published thus far. “Everybody knows (that structural racism is the problem) and all we’ve gotten is lip service. The truth is, nobody’s doing anything about it,” Chand said.

“Along with other BAME leaders, I highlighted that this particular community were suffering due to inequalities in society.”

Chand was born in 1949, spending his childhood in Shimla, the capital of the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. The eldest of five children, he was raised by his mother (a housekeeper) and his father (a worker for the Indian railways).

Born shortly after the Partition of India in 1947, Chand grew up listening to stories of the horrors of the divide which saw approximately one million people killed. The experiences of his elders taught him of the fragility of life – but also exposed him to the terrible things which humans are capable of.

During the separation of the states, Chand’s parents resided on the India side. Although they lived in a miniscule apartment, they would welcome families coming from the Pakistan side into their home. Their stories showed him the power of community spirit, a teaching he would carry throughout his life. “I learned how important it is that human beings look after human beings,” he said.

He was exposed to the true devastation of health inequalities from an early age, experiences which would shape him forever. As a child, a close schoolfriend died because he had no access to medical care. The death traumatised Chand, who questioned why healthcare should be a thing of privilege rather than the right of every human being.

While training as a doctor at a hospital in Delhi, he met a male patient who had broken his wrist. The man was a rickshaw puller and had fallen from his vehicle. Although doctors plastered up his wrist, the rickshaw puller returned days later with the bandage removed.

“We tried to explain that removing it would mean he would have problems with the bone, or even be crippled, for the rest of his life,” Chand recalled.

“And the man replied, ‘I have four kids in my house, and I have not been able to feed them for two days. It is more important that I go back to work, rather than keeping my wrist in plaster’. That experience has always stayed with me – the extent of how large these health inequalities are.”

Chand came to the UK as a junior doctor in the late 1970s. Although he took great pride in working for the NHS and saw the positive impact of easy-access healthcare, he also faced discrimination and racism on frequent occasions. Within his first month, he had visited a local pub in Manchester with other junior doctors hailing from south Asia. The medics were taunted by some individuals in the pub, who aimed racist slurs toward them and began threatening them.

A physical fight broke out and the police were called.

“My first exposure to racism was a very bitter one,” he said, recalling other occasions when patients would refuse to see him and requested a white doctor instead. “As my career grew, I saw that if you applied for a job and your name was something like Kailash Chand, you were not even shortlisted. That kind of racial discrimination inspired me to get into medical politics.”

Sadly, the father-of-two has suffered great loss in his life. His teenage son Amit passed away in 1988, due to heart failure. It was a complete shock for the family and a “very sad” period for them all, Chand said. Despite only having brief time with his son, Dr Chand said Amit

taught them all many things. “He taught us what patience is and what real unconditional love is,” the doctor reminisced.

His wife Anisha Malhotra, who was a GP, sadly passed away in 2018. The pair had been married since 1974. Describing his late wife, Chand said she was devoted to looking after people. The couple’s youngest son Dr Aseem Malhotra has followed in his parent’s footsteps and is a consultant cardiologist in the NHS.

“He is so passionate about the real truth of health care,” Chand said, praising his son for his work on investigating the root causes of illnesses such as heart disease.

Despite Chand being retired as a GP, he is still considered an influential voice in the field and stays active in his battle for equality.

A regular contributor to The Guardian, The Mirror, iNews and Eastern Eye, the doctor writes on anything from the NHS workforce crisis to the institutional racism within the service. Most recently, he was appointed honorary professor of health and well-being by Bolton University. He is also trustee of the homelessness charity Greater Manchester Mayor’s Charity led by mayor Andy Burnham, whom Chand counts as a “good friend”.

Although Chand is still working hard, he does allow himself some time to relax with his favourite pastime. “I love poetry,” he revealed. “I write poetry, recite poetry and listen to it. That keeps me sane – particularly in lockdown!"