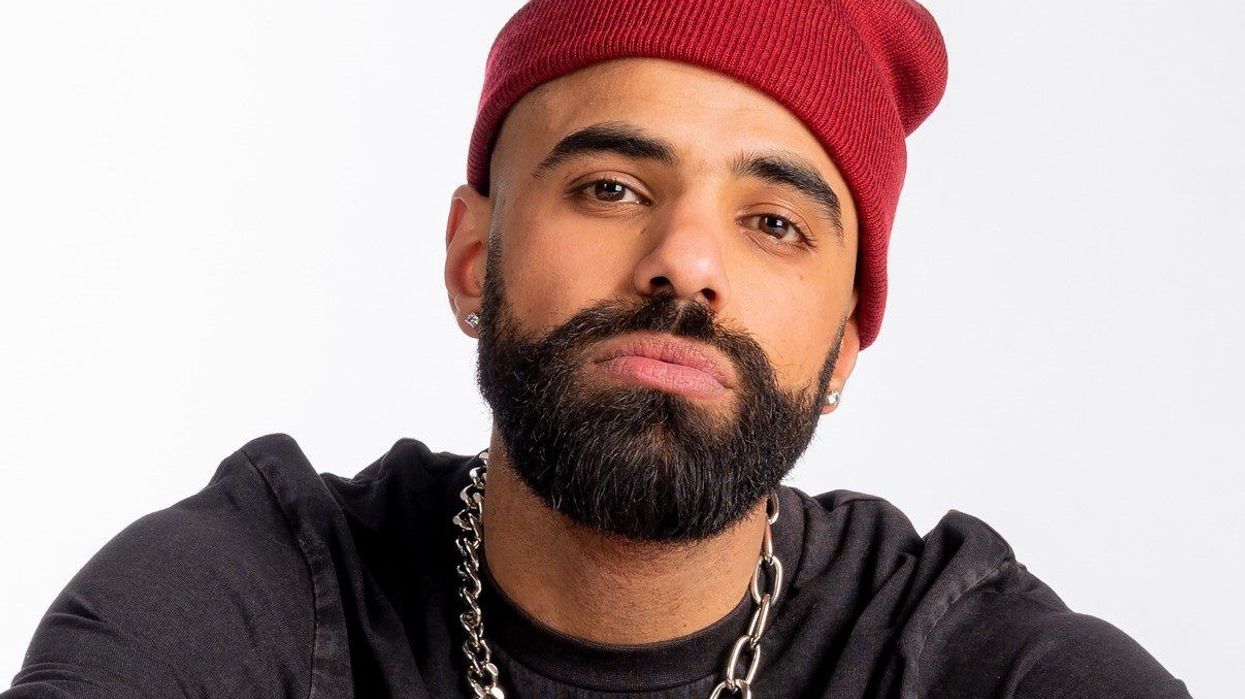

ONE of the most interesting and unique music acts to emerge in recent years is amazingly talented artist Ahmed Khan.

The independent singer-songwriter from Belgium has combined multiple languages, musical influences, and cool collaborations to create unique tracks that have connected with music fans from different cultural backgrounds. That includes his catchy recently released bilingual urban desi song Daily, which saw him team up with popular British singer Arjun and follows on from big previous collaborations that have clocked up many millions of YouTube views.

Eastern Eye caught up with the Belgian breakout star you will be hearing a lot more about to discuss his single Daily, music journey and future hopes.

How do you reflect on your journey?

It’s been a continuous learning curve. With every project I’m learning new things about myself, my sound, and my audience. I have been doing music for a while now, so feel like I am at my peak and my best work is yet to come.

Which among your songs is closest to your heart?

Fake love is probably closest to my heart. On this musical journey, I’ve met a lot of amazing people, but I’ve also realised how fame and stardom was attracting a lot of fake people in my circle. It’s something that was frustrating me more and more, and I just felt like expressing it through the song. I feel like I really managed to capture the emotion on that record without having to try too hard. It was performed and written very organically.

You have done some great collaborations, but which did you enjoy most?

The most recent one with Arjun has to be my favourite. The result of the song was exactly how I had imagined it would be, and the whole collaboration was very organic with no complications. Arjun’s a very easy artist to work with and the whole process was really smooth.

What led to your song Daily and working with Arjun?

Daily is a song that sums up my sound as an urban Punjabi artist, especially with the French and Punjabi fusion on the vocal side. I wanted to round it up with a verse from an artist that would give the song a completely different take. When the opportunity came to get Arjun on to the record, I felt like there was no better song than Daily, for him to get a verse on.

Which of your unreleased songs are you most excited about?

There’s a feature I am working on currently with Firstman. I think it will be one of my biggest releases to date. I’m very excited to get that one out.

Who would you like to collaborate with?

My dream collaboration at the moment would be with an artist called Hamza, who’s from the same city as me. I feel like the marination of our sounds would be unique.

How much does live performance mean to you and what has been the most memorable?

Performing live is the ultimate joy as an artist. Having the crowd know all of your songs and singing them back to you excites me to carry on and keep making more music. I haven’t performed as much as I’d want yet, but performing at Oslo Mela in November 2021 was a lot of fun. The crowd in Norway is very reactive and involved.

I’m very open to different genres, it really depends on my mood. Some days I feel like listening to deep house and other days I’ll be listening to trap/drill records. The music I enjoy most is the one I can connect to on a higher level than just a mood; those are the ones that really sit well with me.

If you could master something new in music what would it be?

I’ve always wanted to learn bass guitar but never got around to it. I was a huge fan of Kurt Cobain when I was younger and always wanted to learn the guitar watching him perform live.

What inspires you?

My continuous struggle to break down barriers as a south Asian artist from Belgium where the Punjabi music scene is pretty non-existent. I’ve always felt I’ve had it harder than many others who are from a territory that is more familiar with the sound. This is my main motivation and inspiration, to prove to myself and others around me that it can be done.

Why do you love music?

The part about music that I love most is the song’s creation in the studio. Putting a song together and being able to express an emotion through the record is the most satisfying feeling for me. Especially, when it manages to connect with the audience, and they can relate to it.

Instagram: @ahmedkhansoundz