Positive word of mouth from enthralled readers will carry a book to great heights and is perhaps more valuable to authors than any critical acclaim or literary awards. That was perfectly illustrated by Abraham Verghese’s popular novel Cutting for Stone, which sold over 1.5 million copies in the USA and remained on the New York Times bestseller list for over two years.

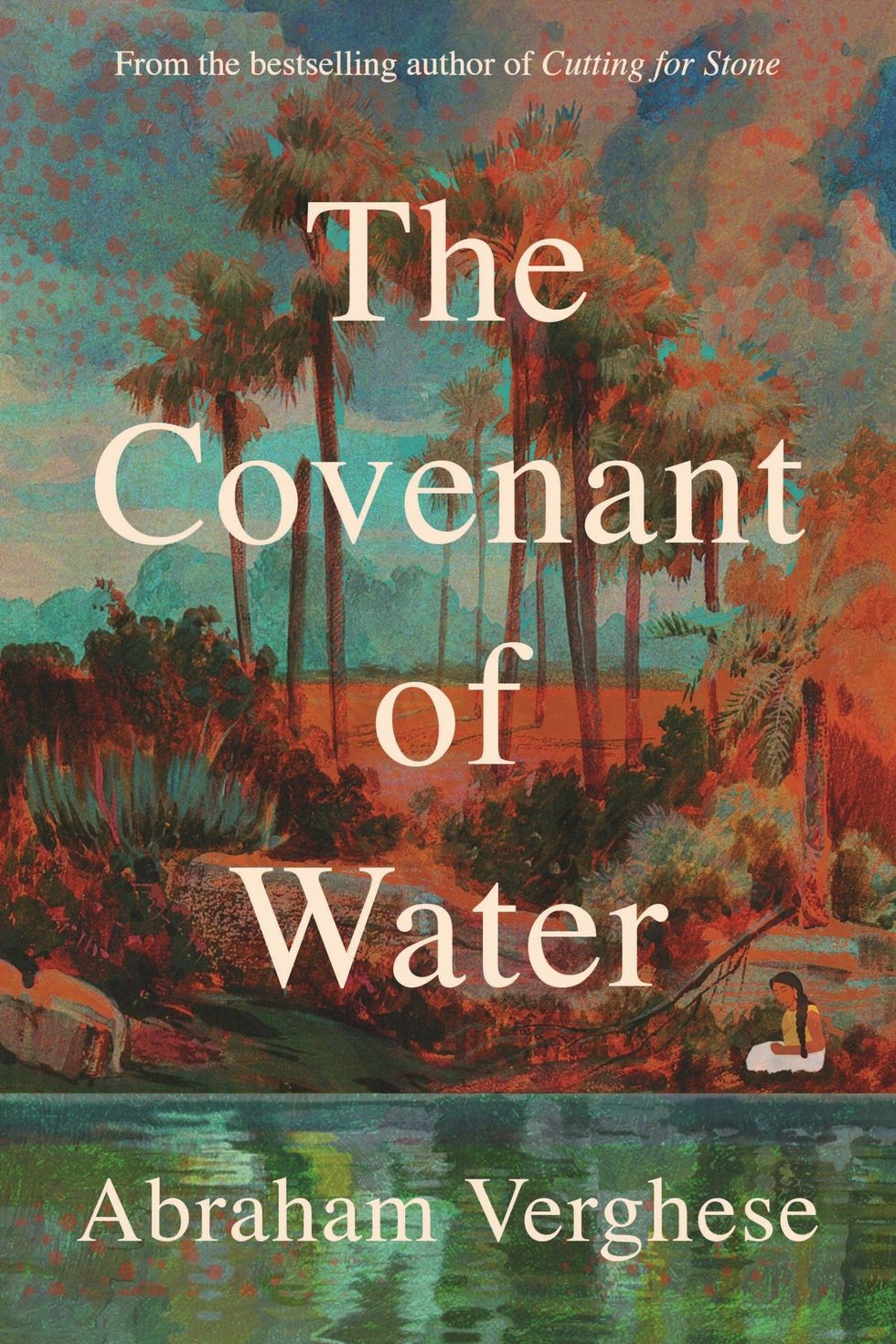

The author follows up that literary phenomenon with his new novel The Covenant of Water, which follows a family in southern India that has had at least one person drown in each generation, from 1900 to 1977.

The epic story of love, faith, medicine, deep human emotions, and humour has been described as a shimmering evocation of a lost India, the passage of time and essence of life.

The American physician turned author adds to his impressive body of literary work, which also includes his books My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story and The Tennis Partner.

Eastern Eye caught up with the writing talent to discuss his new novel, the stunning success of his book Cutting for Stone, key inspiration and how working as a physician informs his writing.

What first connected you to writing?

In the mid 80s, as an infectious diseases specialist in a small town of 50,000 in rural Tennessee, I was seeing more patients with HIV than predicted – AIDS was considered an urban disease. I realised I’d stumbled onto an American paradigm of migration: young men who left their small towns quietly along with the general exodus for jobs and education, but they left because they were gay. They were returning decades later to their families having contracted the virus and with no one to care for them.

I felt compelled to capture the heartache of their journey, the grief of their parents, and my own grief at witnessing the tragedy.

How do you reflect on the incredible success of your book Cutting for Stone?

It feels unreal that a story set in a geography so foreign to most readers could resonate strongly with themes in their own lives. Credit to Robin Desser, my editor, and the late Sonny Mehta for thinking otherwise.

Is there any one moment from that book’s remarkable journey that was the most memorable for you?

The book didn’t do well in hardback in America because of a terrible early review in the New York Times. But in paperback and thanks to book clubs it blossomed. I recall going to a bookstore for a reading I was to do and finding it difficult to park. Once in the store I saw why it was standing room only. I knew the book had arrived.

What is the inspiration behind the unique subject of your new novel The Covenant of Water?

Twenty years ago, my five-year-old American born niece asked my mother, then in her 70s, “What was it like when you were a little girl?” That question prompted mom to pen a 100-page manuscript, complete with illustrations, detailing family stories and everyday life. I knew the stories well. My mother’s notebook reminded me that the unique geography and the distinct character of the insular community of St Thomas Christians would be a great setting for a new novel.

Tell us about the new book?

The Covenant of Water is about the Parambil family, living in present day Kerala, between 1900 and 1977. In this land of 44 rivers, countless lakes and streams, the family has a secret: in every generation, going back seven, at least one member has drowned unexpectedly, in a land where everyone swims. The ‘condition’ (as the family calls it) seems to be inherited, a familial disorder. I won’t say more lest I give too much away. The book is about love, faith, family, medicine, and my thesis that families are bound not just by blood but by secrets.

Who are you hoping connects with this story?

My aim is always simply a good story well-told. Fiction is the ‘lie that tells the truth’ and if the story works it is because the ‘truth’ resonates broadly. As I write I have a discerning reader in mind, someone who I must make suspend disbelief, enter the world I created and feel like she/he has lived generations, yet when they reach the end, are shocked to find it is just Tuesday.

Do you have a favourite moment or chapter in the story?

The book is comic in some sections, and some of those are my favourite, such as when a translator takes liberties conveying the sermon of a visiting preacher. Also, the first and last chapters are important, and what I laboured most over, so are favourites.

Did you learn anything new writing this book?

Every book is a completely new learning process. Previous success gives you nothing when you look at the first blank page.

How much does working as a doctor inform your writing?

There’s a sensibility I bring to writing that comes from my day job. Physicians practise intense observation, parse out the patient’s stories, and use Occam’s Razor to make a thesis from seemingly disconnected details. Also, the suffering I hear about or witness at work perhaps brings a recognition that normal can quickly change to something else. When I sit down to write, that sensibility lingers.

Does the success of your book Cutting For Stone put added pressure on you?

One’s innocence vanishes with the very first book. This is my fourth, and the previous three were well received and still in print. The pressure is self-inflicted, but it has less to do with commercial success than satisfying the discerning reader and hoping not to disappoint them.

What kind of books do you enjoy reading?

I’m biased towards fiction, and especially large, ambitious stories. I will read mystery novels for fun and rarely remember anything about the plot when I am done.

What would you say inspires you as a writer?

Great writing. And the magic of words on a page creating a mental movie that is unique to each reader.

What can we expect next from you?

Probably another novel, though its elements are illformed in my mind just yet.

Why should we pick up your new novel?

Why indeed! I believe the story in a land exotic to most readers still has truisms that apply to us all. I hope The Covenant of Water entertains, surprises, brings you to tears, and lingers long after you finish.

Abraham Verghese is the author of The Covenant of Water, published by Grove Press UK on Thursday (18), in hardback, £20