ACROSS the Asian subcontinent 80 years ago, the guns finally fell silent on August 15, the Second World War had truly ended.

Yet, in Britain, what became known as VJ Day often remains a distant afterthought, overshadowed by Victory in Europe against the Nazis, which is marked three months earlier.

That oversight does a disservice to the millions who fought, died, and suffered in Asia and the Far East. Among them were the staunch Indian Army soldiers Britain had drawn from the sub-continent to form the backbone of the Allied ground forces in the Asia-Pacific theatre of war.

A significant majority of Allied troops who fought against Japan in southeast Asia were from Commonwealth nations, the largest contingent came from modern day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal. These brave men represented every faith and culture, every region, and stepped forward to do their righteous duty.

They were met with some of the fiercest fighting of the war in the harshest conditions, from searing jungles, through monsoons and horrific diseases. Their sacrifices were immense and their example inspiring, but their heroism has never been as prominent in popular narratives on the Second World War as those who fought equally bravery for our freedom in Europe.

It is high time that was addressed, and during this 80th anniversary year of VJ Day, we are changing it.

As a trustee of the Commonwealth War Graves Foundation and a veteran deeply invested in commemoration, I’m proud that we are using this moment to go beyond the act of commemoration to educate and redress historical disparity. Our For Evermore Tour shines a light on the diverse global forces from across the Commonwealth who helped secure victory in Asia. We’re hosting education and community events in Hong Kong, Kenya, Singapore, and Thailand, nations whose people fought and fell under the Southeast Asia Command banner. We are sharing their stories as central chapters of our shared history.

The reasons why this part of the story has been oft neglected are complex. The war in Asia was longer and more complicated than its European counterpart. It lacked a singular turning point like D-Day or the liberation of Paris. And many of the soldiers who fought there came from colonial armies. After all, the Second World War was an imperial conflict in which extant empires mobilised global resources to fight. The heroism of brown and black men did not fit neatly into Britain’s post-war narrative and the subsequent movement for independence across many of her colonies.

That disconnect is still keenly felt today, with Savanta polling showing that half of those identifying as Asian agree greater education is needed on war zones outside Europe.

But the narrative is being challenged. As a migrant community, the start of our story, and contribution to Britain, is not fresh off the boat in the 1950s and 60s, but rather on farflung battlefields where our forebears spilt blood in the name of King and this country.

The Indian Army under the British was the largest volunteer force the world had ever seen. By 1945, more than 2.5 million people from the subcontinent were in uniform. They fought across the globe, from North Africa to Italy, but their role in Asia was pivotal. Be it Kohima or Imphal, Mandalay or Rangoon, Malaya or Hong Kong.

One such brave was 29-year-old Naik Nand Singh, a Sikh from Mansa, Punjab, who in March 1944 led a section near Maungdaw up a steep ridge under heavy machine gun fire to capture a trench. Despite sustaining injuries, including to his face, he crawled alone to capture a second and third.

Another is 23-year-old Naik Fazal Din, a Punjabi Muslim from Hoshiarpur, whose unit came under attack in Meiktila in March 1945. Despite being stabbed by a Japanese sword, the mortally wounded soldier fought on to subdue several enemy combatants while rallying his men.

And who could forget Subadar Netra Bahadur Thapa of the 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles? In June 1944, with his post under siege, he led his men through the night and refused to retreat despite being wounded. At dawn, with only two men left alive, he charged the enemy and died in handto-hand combat. But he delayed the enemy long enough for reinforcements to arrive.

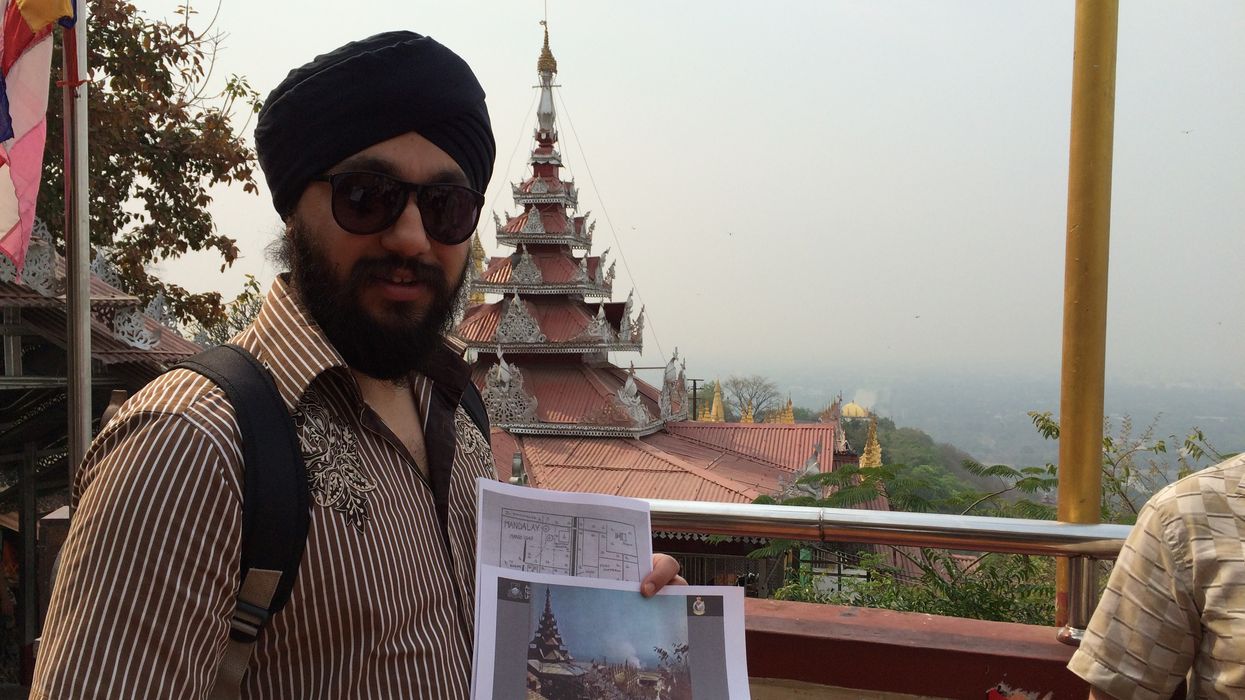

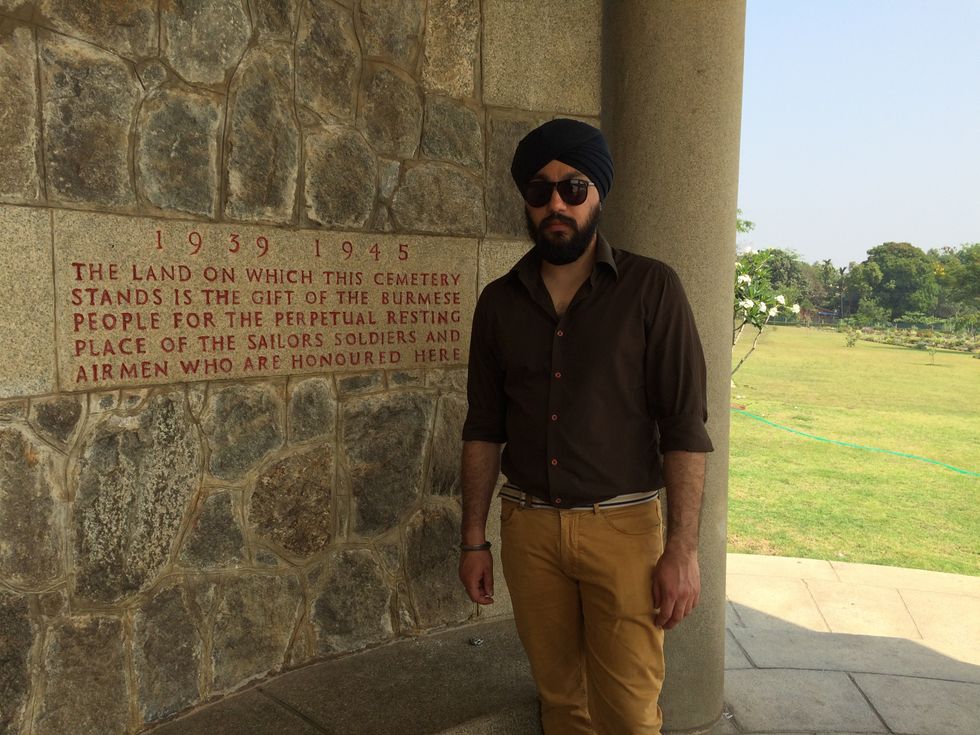

All three received the Victoria Cross, joining 18 other VC recipients from the Indian Army; men who are commemorated on the Rangoon Memorial, which I had the privilege of paying my respects at on a visit to the battlefields of Burma a decade ago.

These are but a mere glimpse of tales of individual gallantry, which alongside many thousands more stories of the brave weave together to form a tapestry of devotion to duty, discipline and sacrifice.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) works tirelessly to ensure their legacy is not lost to time. It maintains the graves and memorials of more than 580,000 Commonwealth service personnel who died during the Second World War, including over 15,000 between VE and VJ Day. It also commemorates 68,000 civilians, whose deaths remind us that the cost of war extends far beyond the battlefield.

Through the charitable arm of the Foundation, we are expanding education, digitising archives, and working with communities to uncover forgotten stories. In Kenya, one project helps veterans share memories of fighting alongside Indian units in Burma, while another brings British schoolchildren face-to-face with the legacy of war through digital storytelling and site visits. Earlier this year, I was privileged to witness the unveiling of a new memorial in Cape Town dedicated to the South African Labour Corps. Many more initiatives to remember the forgotten are planned.

These efforts matter. Two out of five people (42 per cent) who identify as Asian say learning about the human cost of war through personal and veterans’ stories worldwide has more impact than reading history books or watching films. That is why the CWGC is investing in storytelling – not only to inform, but also to move and connect.

For me, commemoration is personal. As a British Army veteran and founder of the UK’s first national Sikh war memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum – created to ensure my community’s sacrifices in the First World War are recognised far and wide – I volunteer with the CWGC to ensure all who served are remembered equally, whatever their background, faith, or rank. That matters more now than ever. In an age of identity debates and fragmented politics, commemoration highlights our shared heritage and values in the face of oppression, and has the power to unify.

This VJ Day, let us tell the whole story. Let us honour those from across the Commonwealth who served, fought, and sacrificed for our freedoms. Let us share and teach their stories, and reflect on where we would be without their contribution 80 years ago. They helped shape modern Britain and deserve to be remembered in all their glory – for evermore.