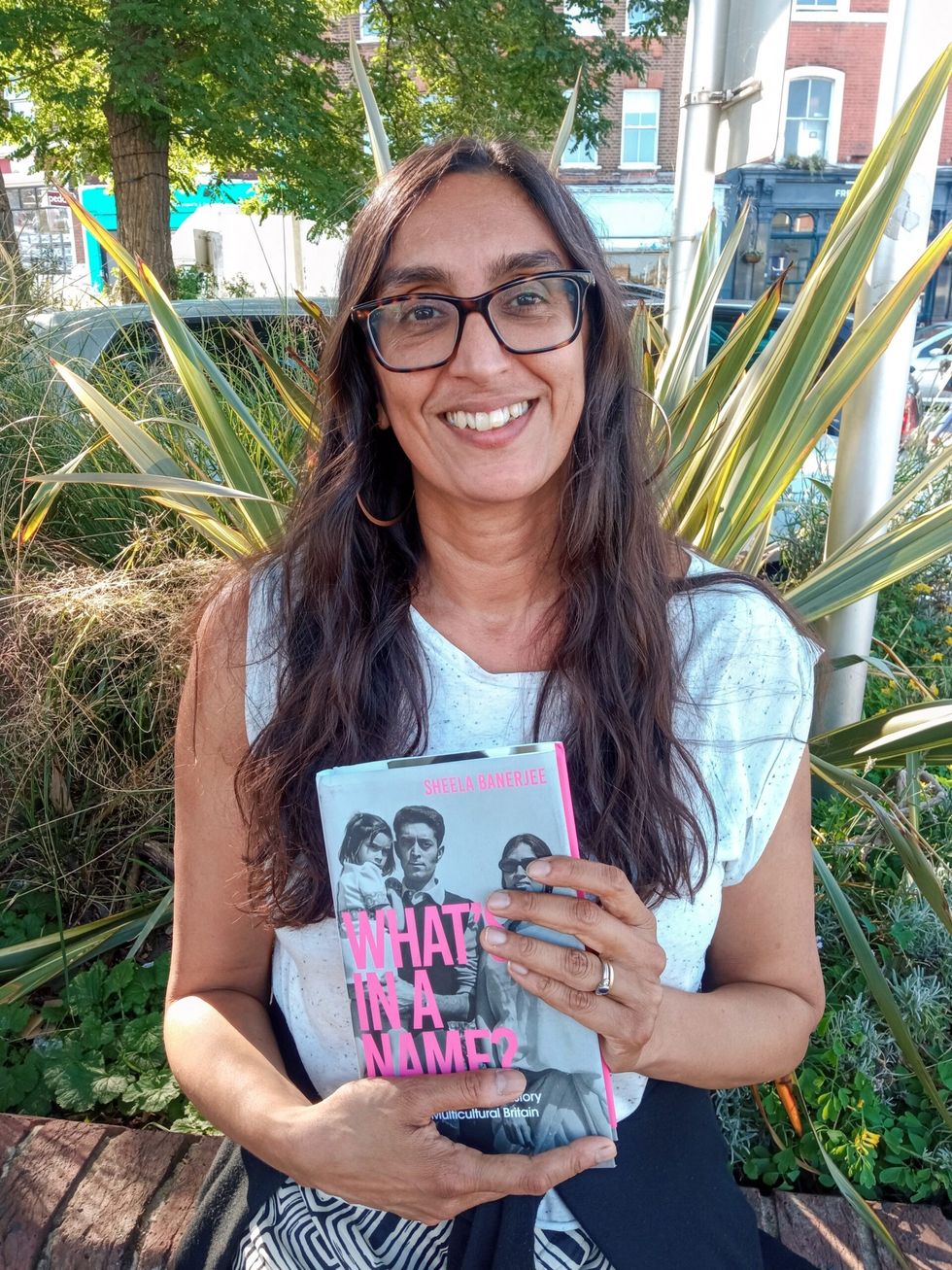

IN HER book, What’s in a Name? Friendship, Identity and History in Modern Multicultural Britain, the author Sheela Banerjee deals with the question which confronts all British Asian parents.

What should they call their newborn? Most want the name to reflect the child’s ethnic and cultural heritage, but at the same time, not be so Asian that it becomes too difficult to pronounce in the playground, or worse, becomes something that other children can turn into a cruel joke.

In her book, Sheela writes of a girl called Denise with the Sinhalese Buddhist surname, Seneviratne. This got turned into “Son of a rat”, “Son of Acne”, or simply “Ratty”.

“I hated Seneviratne,” Denise admitted.

No one has summed up the dilemma better than William Shakespeare in Romeo and Juliet: “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose/ By any other name would smell as sweet.”

At school, Sheela could just about tolerate her first name because it sounded like the conventionally spelt, “Sheila”. But she hated “Banerjee” and did her best to distance herself from anything that might be construed by English children as “Indian”.

It didn’t help that it was British colonial rule that has caused Bengalis to change the original surname of “Bandopadhyay” to Banerjee.

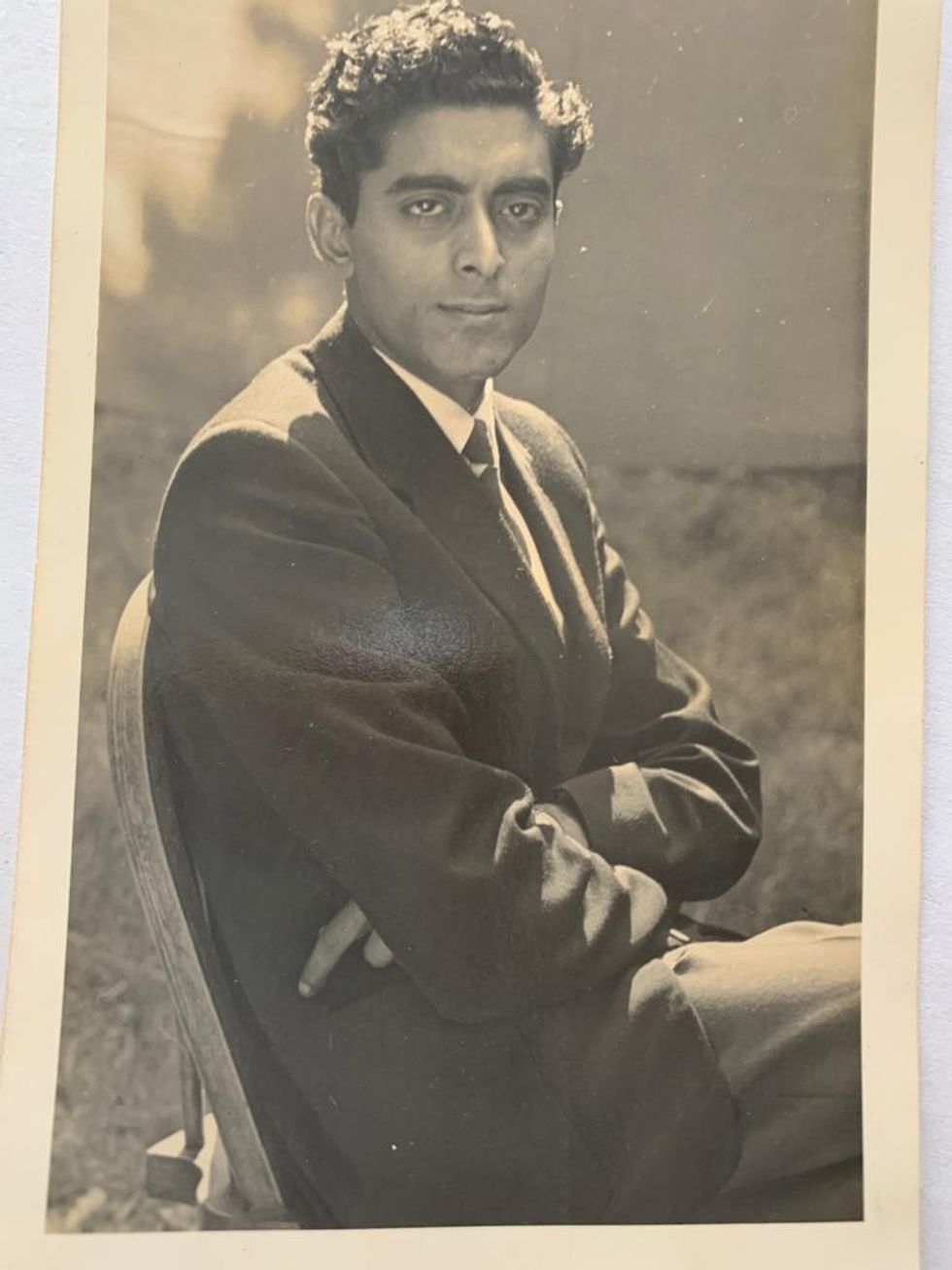

Sheela’s story is unique in that her father, Balaji Prasad Banerjee, dragged his family back to India from the UK, not once but twice, with the idea of returning home for good. But since the experiment did not work, he eventually came back to Britain, with Sheela switching schools several times.

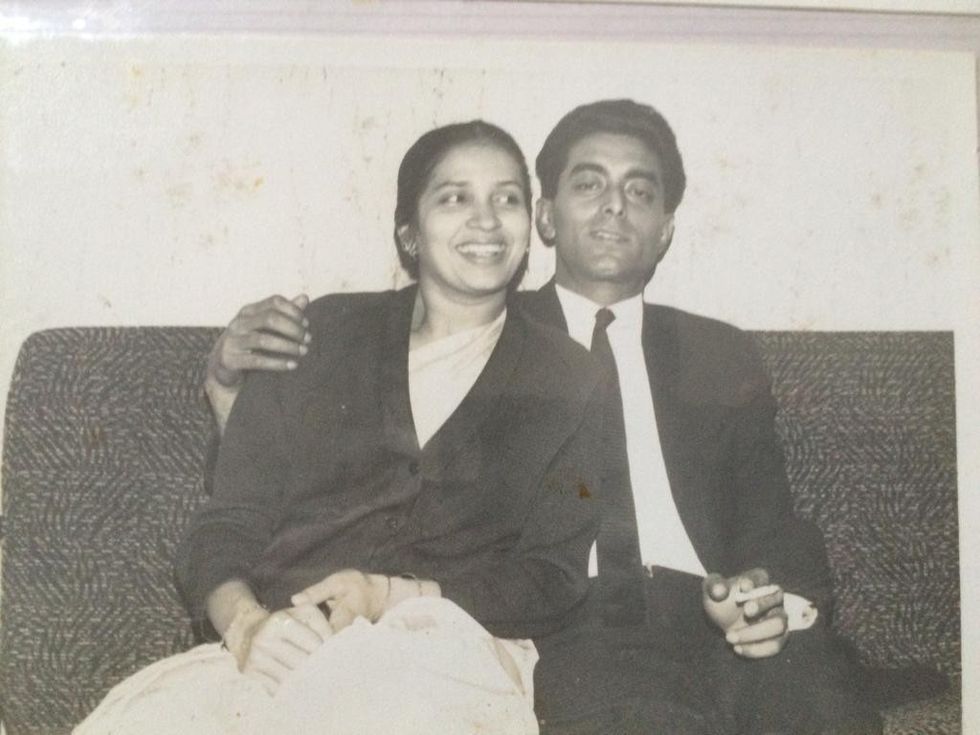

He came to Britain in 1959, aged 22, from Chandannagar, the former French settlement of Chandernagore in the Hooghly district in West Bengal. This was primarily to escape his domineering father. Balaji travelled to India in 1966 and came back to London with his wife, Tripti. After Sheela was born in Hammersmith Hospital in 1967, he spent the next couple of years alone in India.

He made another attempt at settling in India when Sheela was four, between 1971 and 1974. This did not work, and neither did a second attempt at living in India between 1979 and 1980.

Balaji and Tripti, who turned 85 and 80, respectively, this year, have lived in Britain since 1980.

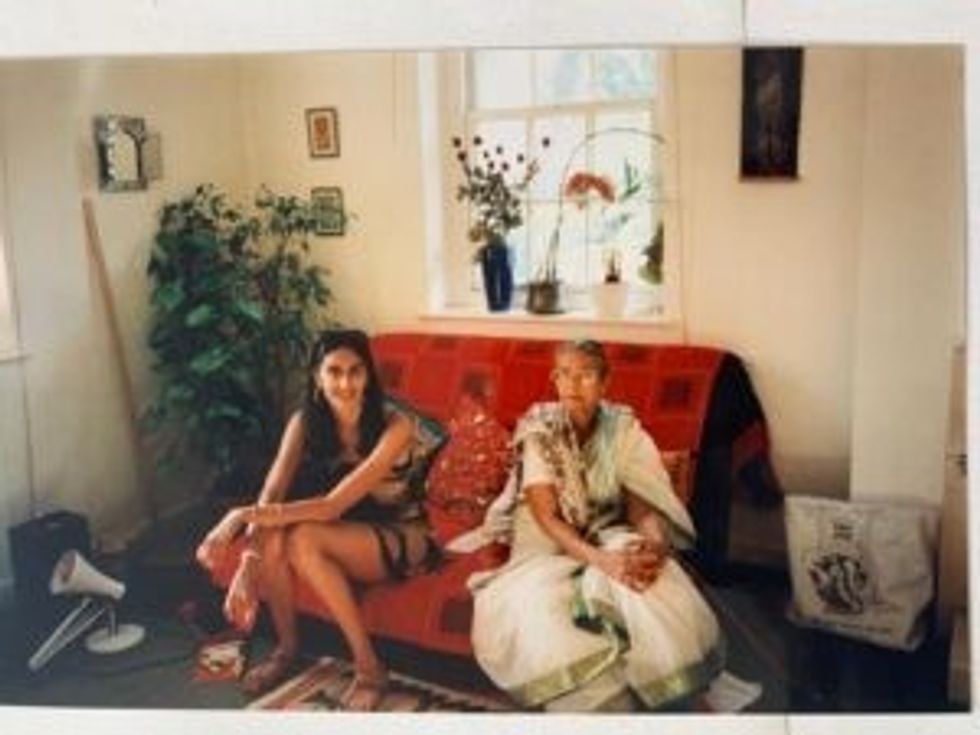

In India, other children marvelled at Sheela’s “English accent” and understood that her surname meant she was a Brahmin, a member of the highest caste. But at school in Hayes, which was an especially racist place in the 1970s, Sheela would try and put on a cockney accent so that she wouldn’t be picked on as an outsider. It was not until her 30s that Sheela came to be proud of her ethnicity and her origins.

“I am grateful my parents put two ‘ee’s in Sheela. My mother explained the name came from Satya Narayan Puja. It made me feel a lot more comfortable about my name,” writes Sheela.

“At school, although I loved lots about India, I was very sniffy about it. I didn’t value the culture. I was seeing it with the mind of an English person. I kind of regret I carried on like that into my 30s.”

When she and her husband, Dollan Cannell, had a daughter 15 years ago, they considered many choices – Sulakshana, Shahanara and Durga among them – before settling on “Ishaana”.

“Pronounced in Bengali, it’s ee-shaanaa, with even stresses on all three syllables, a parade of long, luxuriant vowel sounds and soft consonants. Pronounced in English, it won’t sound quite like that, but the name will survive the transliteration.” She feels “it’s perfect. I’m not a devout Hindu. But the name catches a memory, a fleeting glimpse of a building, the old town hall at Belsize Park where every year we would go for the annual Durga Puja festival – our equivalent of Christmas, I would say, as I tried to explain it to English friends.

“In my mind, the name Ishaana contains an element of that time.”

Whatever former home secretary Suella Braverman may say, it is also an indication that multicultural Britain works and in 2023 is largely at ease with itself.

Incidentally, Suella, who is married to a Jewish husband, Rael Braverman, was born Sue-Ellen Cassiana Fernandes. She has shortened her first name.

In her book, Sheela has written about the names of several of her friends and colleagues, but no tale is more poignant that of Liz Husain.

Liz’s late father, John Husain, was born Arif Husain in India in 1926. But when he enrolled at Whitgift Grammar School in 1939, Arif mysteriously became John and the change proved permanent. Arif had come to Britain in 1939 with his mother, Olive Husain, and his siblings. But Arif’s father, Qazi Mohammed Husain, a senior employee of the fabulously rich Nizam of Hyderabad, remained in India while war raged in Europe.

The Cambridge-educated Qazi had met and married Olive Stowers in England in the 1920s. Little is known of her background. She might have been a servant girl or worked in a shop. They made a life in Hyderabad, where their marriage appears to have been blissfully happy. For one thing, Qazi, who read maths at King’s College, Cambridge, was pro-vice chancellor of the Nizam’s Osmania University. The Nizam himself featured, dripping with jewels, on the cover of Time Magazine in 1937.

However, when India was partitioned, Qazi moved to Lahore, apparently to visit relatives or test the waters. In June 1947, “Olivia Husain received a telegram saying her husband had died in the Albert Victoria Hospital in Lahore”.

After the war, Olive travelled to India, but was unable to get back the beautiful white house her husband had built in Hyderabad anticipating his wife’s return. Liz’s father, John/Arif, remained largely silent about his origins in India.

All that remains of the past is an evocative black and white photograph of the Husain family taken in Hyderabad in 1938. Arif, as he was then, was 12, smart in shorts and a blazer positioned on the left of the picture.

“But it is a moment frozen in time, as history swirls around all the subjects in the photograph,” comments Sheela. “Arif Husain, the young boy, will find war, Indian independence and Partition mean that in a few months’ time his life will be irrevocably altered – he will go from being a secure Indian schoolboy in an affluent, Indian Muslim family, the son of a pro-vice chancellor at a Muslim-run university, to living in semi-poverty in war-ravaged London, his Indian father becoming a distant memory.”

Liz has learnt a little more about why her surname is Husain and, with Sheela’s help, been able to reclaim something of her own history. One can only speculate that a teacher changed the name Arif to John so the boy wasn’t picked on by other schoolmates. John closed the door on his Indian origins, though he kept his surname.

Sheela talked to Eastern Eye about her schools in England, first at Wood End Park Junior School in Hayes, and later, after her second spell in India, at Swakeleys Girls High School in Hillingdon.

She remembered that Blair Peach, a New Zealand teacher, was killed during an anti-racism demonstration in Southall in 1979. To her, Hayes was a frightening place.

“As the 1970s wore on, it became more and more racist,” says Sheela. “My mum was attacked, my aunt was attacked. My mum was hit across the face. There were ‘Wogs out’ signs. You had to be wary as a child every time you walked down the street. It was vicious, it was horrible.

“We had been through the riots in Southall or grown up with all this racism directed at me, my family and all the other Asians. By 16, I was very political.”

It was a natural progression for her to go to Sussex University to read politics. As for the career she wanted, she is angry she was forced out of television after she was unable to find work making documentaries. She turned to the academic world to regain a sense of her own worth. She says: “I did an MA at Queen Mary College London. I enjoyed it and got a scholarship to do an English PhD at Queen Mary on ghosts in TS Eliot and Virginia Woolf.”

She studied the origin of words and names in such texts as Eliot’s poem, Ash Wednesday, or Woolf’s novels, Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse.

“I didn’t realise it at first, but it is basically taking words, our names, and exploring them in depth, looking at the historical context, how they relate to society, to religion, to literature. It’s really a close reading of our names.”

Sheela makes a point of speaking to her daughter in Bengali. “I know from speaking two languages that I feel quite different in both languages. It’s partly why I decided to speak to my daughter in Bengali because I didn’t feel she would get everything of my personality if I just spoke to her in English.”

Today, apart from having taken up authorship, Sheela works as a freelance journalist and copy and content writer. She is still very upset that her ambitions of making television documentaries have been frustrated. She met her husband when they were working for a production company making programmes for the BBC.

She explains: “I gave up TV. As a state school-educated, non-Oxbridge, brown woman, it is hard. There are not that many of us. If you were trying to make documentaries, it was virtually impossible. We would get shunted off into light entertainment and stuff like that. Which is fine. But that’s not what I wanted to do.

“And also, it’s just rife with discrimination. That’s the problem. And it’s really stressful. It’s still the same.”

She quotes some diversity figures from television. “The number of black, Asian and minority ethnic directors in factual television in 2018 – not that long ago – was like three per cent. I mean it’s absurd. And most of the productions are in London or Manchester, hugely diverse cities. Most programmes are now made by independent production companies, even for the BBC. If you go on to their websites and then ‘meet the team’ pages, there’s a sea of Hannahs and Lucys and Elsas and Charlottes. It makes me so angry.

“There are lots of industries that are exactly the same – for example, academia and publishing. But TV is still really important because lots of people watch it and get their information from it.”

She speaks of a time of hope in the 1990s. “There was Goodness Gracious Me, Bend it like Beckham, Bhaji on the Beach and My Beautiful Laundrette. There was Bandung File, and Farrukh Dhondy at Channel 4 commissioning loads of stuff that told our stories. I don’t see that any more.”

She talks of her daughter’s generation. “My daughter goes to a very multicultural school in Hackney. It has a huge proportion of young ethnic minority girls – Turkish, Bangladeshi, African, a whole mixed group of girls. I don’t see those young girls on TV represented in proper narrative-driven stories. The closest I’ve seen to that is Ackley Bridge, a series for children, basically. These children and their slightly older counterparts make up a huge proportion of London’s population, Manchester’s, Birmingham’s. Where are their stories?”

That neglect might be explained by their names. Sheela concludes her book with the observation: “The names we carry unfold in place and time – we cannot know how meanings and nuances will devel[1]op, what history will bring. I cannot know what society my daughter will live in, what place she will have within it.

“Perhaps my daughter will live in a world where an Indian heritage will become utterly unremarkable in the multiracial mix of fluid identities. “Ishaana will always be in some way Bengali, Manx (from her dad), a Londoner, but also from Hackney, mixed race. Perhaps holding on to past identities is futile in the long run, perhaps it only works for a generation or a few years. But for now, I am happy I gave her the name Ishaana.”

What’s in a Name: Friendship, Identity and History in Modern Multicultural Britain by Sheela Banerjee is published by Sceptre, an imprint of Hodder & Stoughton. £18.99