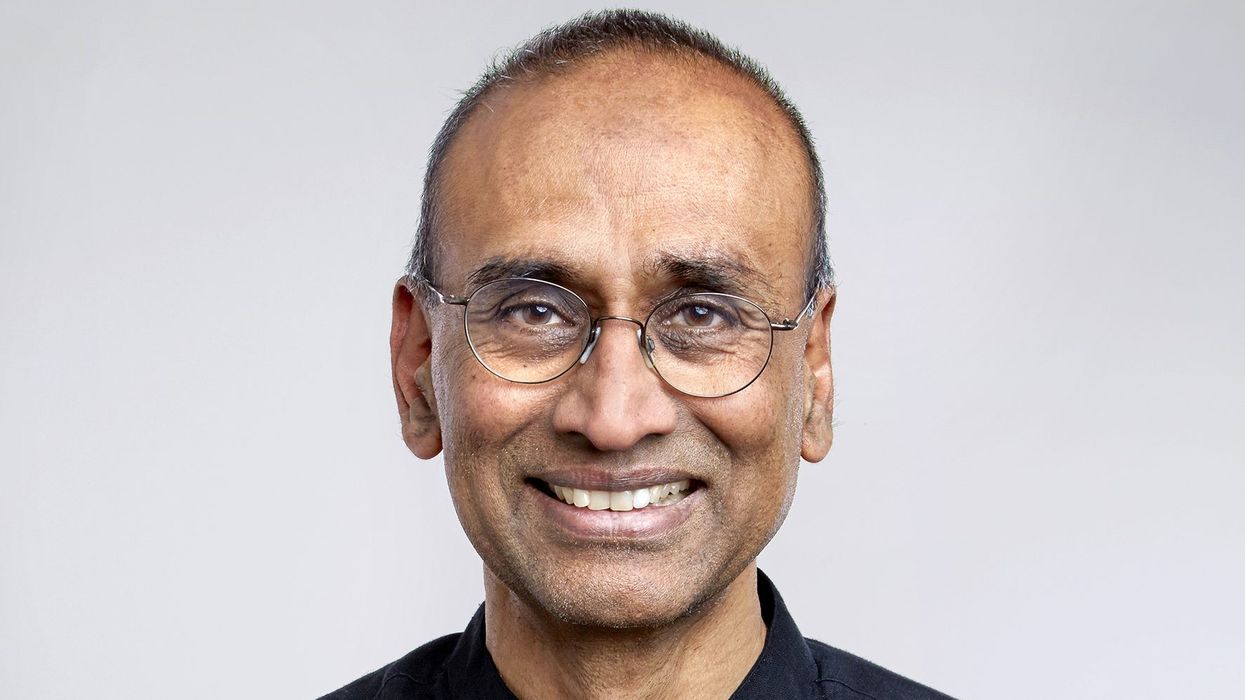

NOBEL LAUREATE Prof Sir Venkatraman Ramakrishnan – or “Venki” as he is commonly known – had a characteristically modest suggestion for GG2: “I think you should take me off your list.”

Meaning, I am not important enough.

Some people are defined by the jobs they do. Venki is not one of them even though he stepped down as president of the Royal Society in December 2020 after five years in the post. In the science world and beyond, he commands enormous respect as almost an oracle offering sane and wise counsel.

He thinks that prime minister Rishi Sunak is absolutely right to recommend that schoolchildren should study maths up to the age of 18. And he supports Sunak’s decision to set up a standalone “Department for Science, Innovation and Technology”.

“That’s a very good thing,” was Venki’s reaction.

He smiled: “You know, I’m not a Conservative politically, I can tell you that, but I have to support that particular move.”

Mathematics, he said, “permeates everything. I mean, if people want to understand how ChatGPT (a chatbot developed by OpenAI) works, the underpinning of it is essentially computer science and mathematics.”

He pointed out: “Mathematics is now making inroads into almost everything. Even social policies are analysed by gathering data and analysing it using mathematical tools. Artificial intelligence is based on mathematics. Encryption, which we rely on, is based on mathematics. Mathematics is now increasingly important in every science, including biology. People need to have some minimum level of mathematical education, just to make sense of the modern world. I’m completely in support of that.”

He said: “Mathematics doesn’t have to be painful, it can be taught in a way that’s interesting and engaging. I don’t buy this argument that, ‘Oh, some people have never been good at maths.’ Everybody can learn mathematics up to a certain level.”

Venki suggested: “There could be two levels of mathematics, one for people who want to go on and study mathematics at university, and somewhat more general level mathematics for everybody else, including people who want to do literature, history or something. This is done in many other countries, including the US. So there’s no reason why it couldn’t be adopted here.

“I also think people should study English and history all the way through to 18. And, increasingly, people should study a foreign language. A well rounded, balanced education is what’s going to prepare people for the future.”

Unlike some right wing commentators who dismissed the setting up of the science ministry as politically a pointless exercise, Venki gives due credit to Sunak.

“Having a science ministry does show he has vision,” commented Venki. “And it it’s not just science, it’s science and innovation, which go together. They never belonged in some broad ministry, some sort of stepchild in some other ministry. The UK is not going to survive, except by being a knowledge based and innovative economy.”

He has been always been a great supporter of the pan European “Horizon” programme, from which the UK has been excluded following the Brexit decision.

“It’s good for both Europe and Britain – Britain is one of the strongest science countries in Europe. If Britain is part of Horizon, it will strengthen European science generally. But even if you look at it from a very selfish, nationalistic point of view, it gives Britain influence on a Europe wide stage. It means that Britain is visible, it becomes a magnet for talent. Horizon can call on a Europe wide pool of experts to assess things, and you’re then forced to compete with the best of 500 million people. It raises the standard for everybody.”

He identified areas where cutting edge research is being done: “It’s strong in the life sciences. There’s a lot of excitement in computer science, and in physics and materials. In biology, there’s the whole problem of neurobiology and circuitry and how the brain is connected and memory is formed and decisions are made. There is cancer biology, that’s an age old problem, but lots of work is being done on it. Aging is a big problem.”

Last November Venki was appointed to the Order of Merit by King Charles. He is thought to be the first person of Asian origin ever to have been honoured in this way. The order is in the gift of the monarch and has been dubbed “the most prestigious honour on planet earth”.

The number of people who belong to the order is restricted to 24 and the honour, established by Edward VII in 1902, is bestowed on those in Britain and the Commonwealth who have made “exceptional contributions in the arts and sciences as well as public life”.

Since he came over from America, Venki has been working on ribosomes at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge. It is for his work on ribosomes that he shared the Nobel Prize with two other scientists in 2009.

“I’m still work at the same lab, in the same job, I never stopped working on ribosomes,” said Venki, who was born in Tamil Nadu in 1952, left India at the age of 19 for higher studies and research in the US, and settled in Cambridge in 1999.

When he got his Nobel Prize, the citation said that “ribosomes produce proteins, which in turn control the chemistry in all living organisms. As ribosomes are crucial to life, they are also a major target for new antibiotics. An understanding of the ribosome’s innermost workings is important for a scientific understanding of life.”

Venki explained: “The information that we need to make the proteins which make almost everything about us – our skin, our eye, hair – resides in our genes. The machine that translates that information into functional protein is the ribosome. What I am trying to do is understand how this very complicated machine works.”

His first book, which came out in 2018, was Gene Machine: The Race to Decipher the Secrets of the Ribosome. He was in Chennai last month to inaugurate publication of the Tamil translation of his book.

He is currently working on his second book, which will be published next year by HarperCollins in the UK and William Morrow in the US. His provisional title, Is Death Necessary?, has been changed by his publishers to Why We Die.

“But I’m not sure that that will be the final title,” said Venki.

The book, he said, “is more about the biology of why we age. Lifespans are highly variable among species. The question is, why don’t we live to be 200 years old like tortoises or 300 years like sharks? And what would it take to do that?

“I think a lot about the biology of various things, you know, processes. There’s no question that we live longer. The real question is, can we live beyond 120?

“I came to the book thinking nothing could be done about it. Now, I’m not so sure. I think it’s highly implausible, but not impossible.”