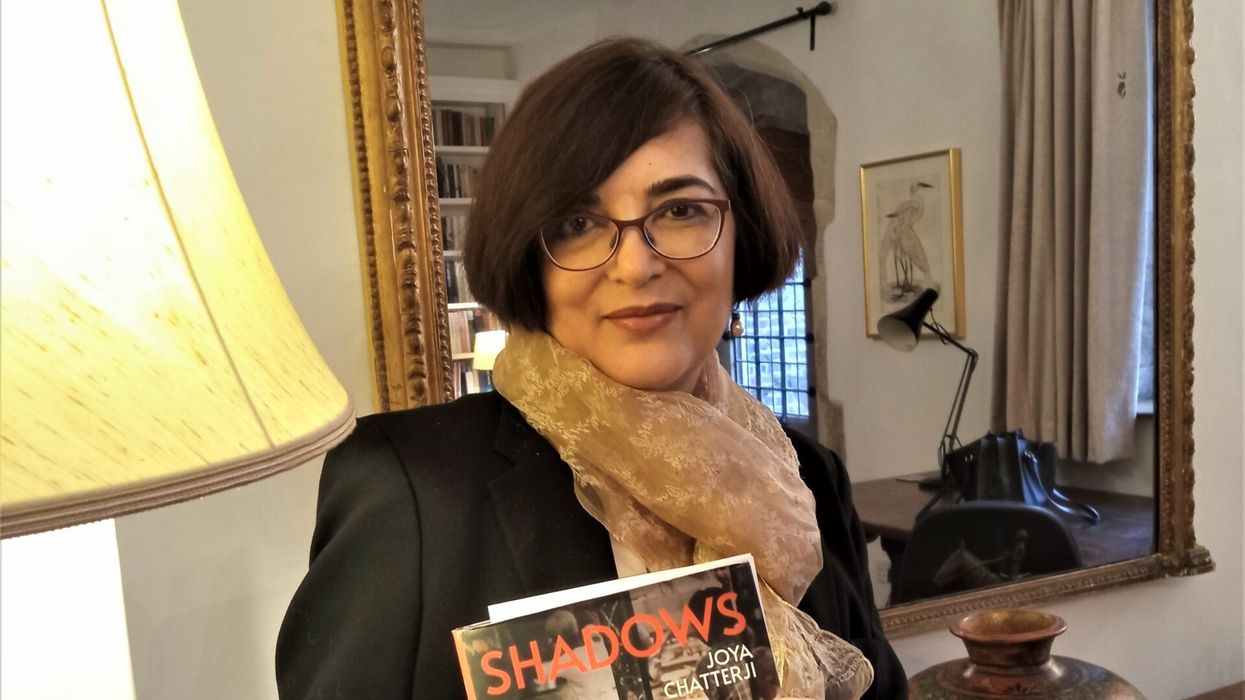

BRITAIN is blessed with many brilliant British Asian historians but Joya Chatterji, a don at Cambridge University, is regarded as someone special. The imprint that she has left on generations of PhD students has been lasting and profound. This year, she merits entry to the GG2 Power List just on the strength of her latest book, which attracted this tweet from author William Dalrymple: “Brilliant Joya Chatterji, Professor of South Asian history, and fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, talks to Pragya Tiwari about one of my books of the year, Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Twentieth Century.”

The book, in which Chatterji has woven the history of the Indian subcontinent over the past one hundred years with that of her own family, has a particularly chilling and uncompromising chapter. She writes that those who pursue romantic love across boundaries of caste, religion or class in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are even today “just asking to be murdered”. One of her former PhD students, Edward T G Anderson, who is now an assistant professor in history at Northumbria University, told the GG2 Power List she was “inspirational”.

He drew attention to the chapter on Acnowledgements in his own book, Hindu Nationalism in the Indian Diaspora: Transnation al Politics and British Multiculturalism: “It is hard to put into words the influence that Joya Chatterji has had on my life. She is the most re markable teacher, advocate, and friend that anyone could hope for. Joya is a person who will provide counsel and sympathy in difficult times, and make a big fuss of you when there is something to celebrate. Joya took a chance on me early on, but the term ‘PhD supervisor’ doesn’t come close to reflecting the role that she performed.

I will never be able to repay the support and inspiration that she provided me with over the years.” So far as the teaching of history in British schools is concerned, Chatterji has been member of the core project team that set up a web site, “Our Migration Story: The Making of Britain”. Over the years, she has urged the BBC and other TV networks to “make partition a British story. Migration has been introduced on to the GCSE syllabus and then the A level syllabus. That includes the fact that there are people who are not Caucasians in Britain, how they’ve been coming over, waves and waves. But it’s taken years and years and years of effort. It’s been a goal of my life to make people wake up, and say, ‘Hang on. There are people here in Britain who happen to be Punjabis and Bengalis. Why would that be so? Do you think it might be something to do with Partition?’ ” Joya (“Joy” to her five siblings among whom she is the second youngest) was born in Delhi in 1964 to a Bengali father, Jognath Chatterji, and an English mother, Valerie Ann Sawyer.

She was passionate about history from a young age, stood “first class first” in her exam results at Lady Shri Ram College, a well-known institution for women in Delhi, and came in 1985 to Trinity College, Cambridge, where she did a three-year degree in two followed by a PhD in the history of Hindu com munalism in Bengal. Poor health forced her to give up day to day teaching in 2019 but she continues to supervise her PhD students in her capacity as “Emeritus Professor of South Asian History.” In Cambridge, she lives with her husband, fellow historian Anil Seal. She has been able to establish a close bond with her students. Those from Pakistan were startled, shocked even, to learn basic truths that had been hidden from them back home.

They knew very little about why East Pakistan had broken away from West Pakistan to form Bangladesh in 1971. For example, they couldn’t believe that East Pakistan constituted 55 per cent of the population of Pakistan. “Are you sure? I mean, really?” they asked her. Back in India, the relationship between guru and shishya (teacher and pupil) is practically of worship of the former by the latter. No questioning is allowed. But Chatterji’s dedication in Shadows at Noon is sincerely meant: “One learns far more from students than one teaches them. This book is dedicated to my brilliant and beloved graduate students, who are (still) my learned instructors.” In an interview with the GG2 Power List, Chatterji spoke about her relationship with her students: “I have a common rule, the first of which is that the very moment they meet me or enter the room, we are equals, fellow toilers in the field of history. I know many are far better than I am today or will achieve more than I have. They call me by name, ‘Joya’, no ‘Professor’ nonsense. When their numbers grew large, I put down inter-student rivalries the second I smelt them. Not with an iron fist, but by explaining why they needed each other. Most have become close friends, essential parts of my life, and also mentees for life. At any given time, at least four are having a crisis which needs my urgent attention. Long after they have graduated, and have jobs in foreign countries or distant cities, I drop everything for them, and they do the same in return.” One sought advice not on her thesis but whether she should have an abortion. She stressed: “Not only do I love them, I feel a sense of duty to them. They have a tigress behind them, and they know that.” She went on: “Recently, they organised a Festschrift conference for me.” This is a German word, used to describe a collection of essays in book form brought out by PhD students to honour their supervisor. “It was awesome to see so much talent in one room and how far they had travelled, how supportive they were of each other and in loving me,” recalled an emotional Chatterji.

She spoke of the battle to make people aware of a wider history, especially of colonialism and empire, that Eastern Eye, for example, has long been covering. She detects change is in the air. “Even European courses and hires have now changed a great deal, so much so that in Cam bridge the history of France is taught by a brilliant scholar who writes from the perspective of Algeria,” she said. “No one can ignore ‘empire’ any more by keeping it in a tidy little sub-section of scholars who studied the non-western world. Outside universities in the area of public history, there has been much growth and awareness, too.” She mentioned David Olusoga’s programme and Kavita Puri’s documentaries on Partition on Radio 4 and commented: “A generation before some people had never heard of the Partition of India. I taught two generations of Britons who knew nothing about it. I say this not in a bad way but the subject was not on the school syllabus. I had to start by showing them a map and telling them to keep it pinned to their board all year, just so that they could visualise where the British Raj had been on the planet