RATNA VIRA, author of Art Under the Indian Sun: Evolution of Artistic Themes in the British Period – it contains stunning paintings of “ordinary” people in 18th century India done on mica – seems to be a renaissance woman.

Or a Delhi celebrity with a very busy life. She writes fiction and non-fiction, paints and collects art.

She talked to Eastern Eye when she was in the country at the end of last year to launch her book at two venues – the Travellers Club in Pall Mall, London, and at the Oxford India Centre for Sustainable Development at Somerville College at the university.

First of all, what is mica?

She says it is used in cosmetics. A fuller explanation is that “mica is a naturally occurring mineral dust that is used in cosmetics to add colour and shimmer”.

She didn’t set out to write the book. It’s just that she chanced upon some mica paintings, until the subject, she admits, became an obsession.

She dimly remembered that “my grandfather, who is from Bihar” – not the most arty place in India – “showed me some mica paintings years ago”.

But why paint on mica at all? Why not on canvas or on paper?

“Mica paintings are on thin mica sheets and they look like glass paintings which were very popular in Europe,” she says. “Mica mimicked that quality of glass. The reason why mica is popular is its luminosity, the fact it is very smooth. The fact that the paint does not sink in made it very vulnerable and brittle. So what remains of mica paintings is extremely valuable in terms of the story they tell and the various themes.

“In India, the mica came from Andhra Pradesh and Bihar. Indian artists began to paint on them. The type of mica used is called Muscovite. One of the theories is that mica was cheaper than paper. In some of the paintings, the artist has painted on both sides of the mica sheet, giving it a three-dimensional effect.”

She holds up the cover of her book: “You see the shadow (from the other side) which gives it the three-dimensional effect.”

In Mughal paintings, “the face is shown in side profile and there’s a lot going on”.

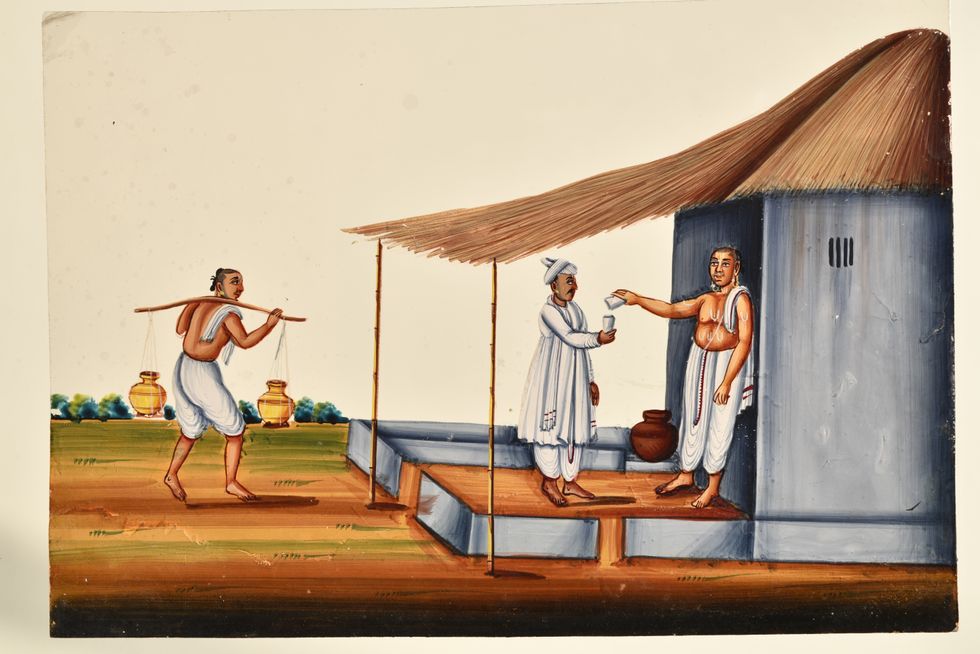

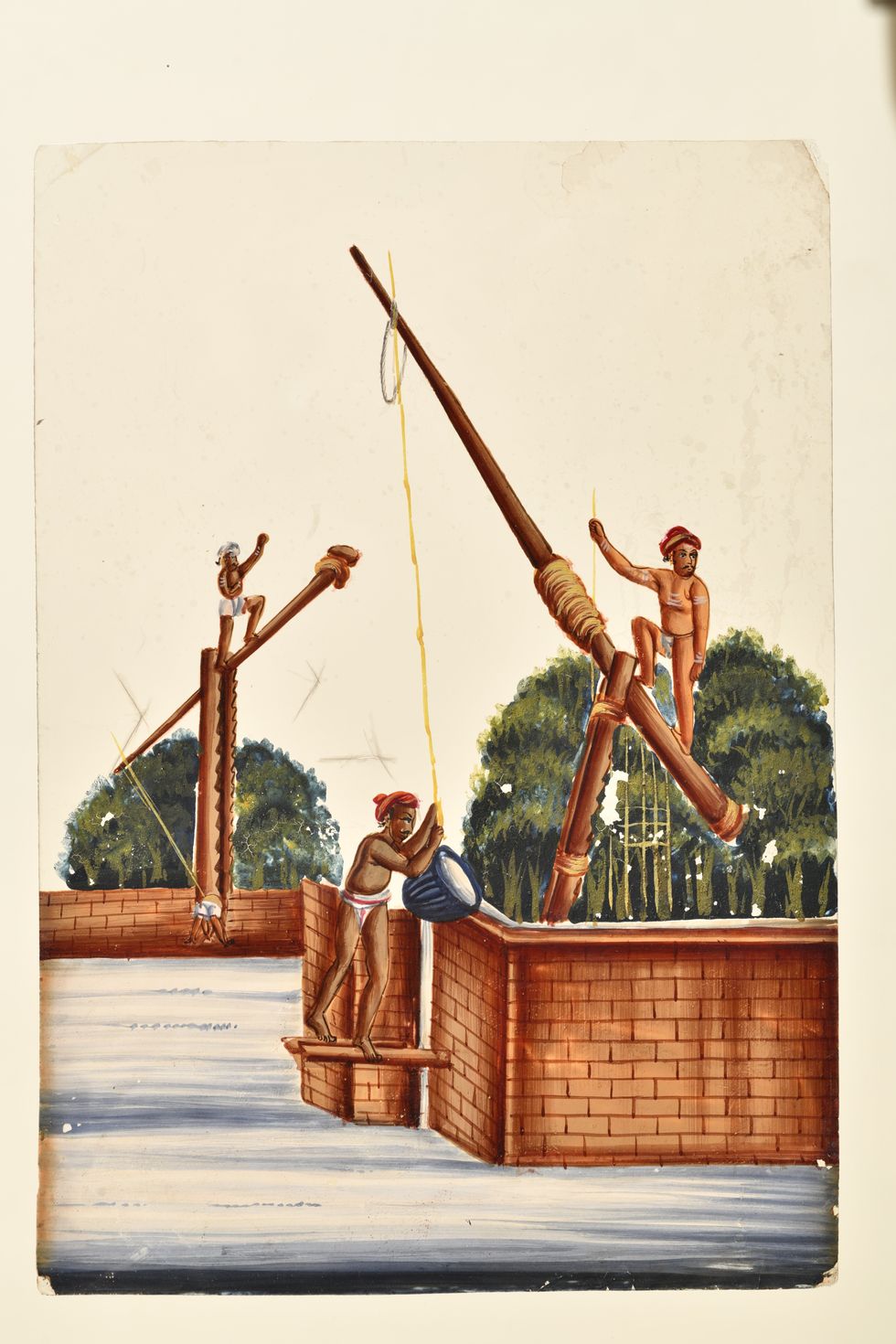

In contrast to the maharajahs and emperors depicted in Mughal paintings, the “common man” was featured in mica painting. There was a change of patrons from rulers to East India Company officials.

The coming of the Europeans brought a “democratisation” of the arts, she acknowledges. “The East India Company officials could afford to buy the art.”

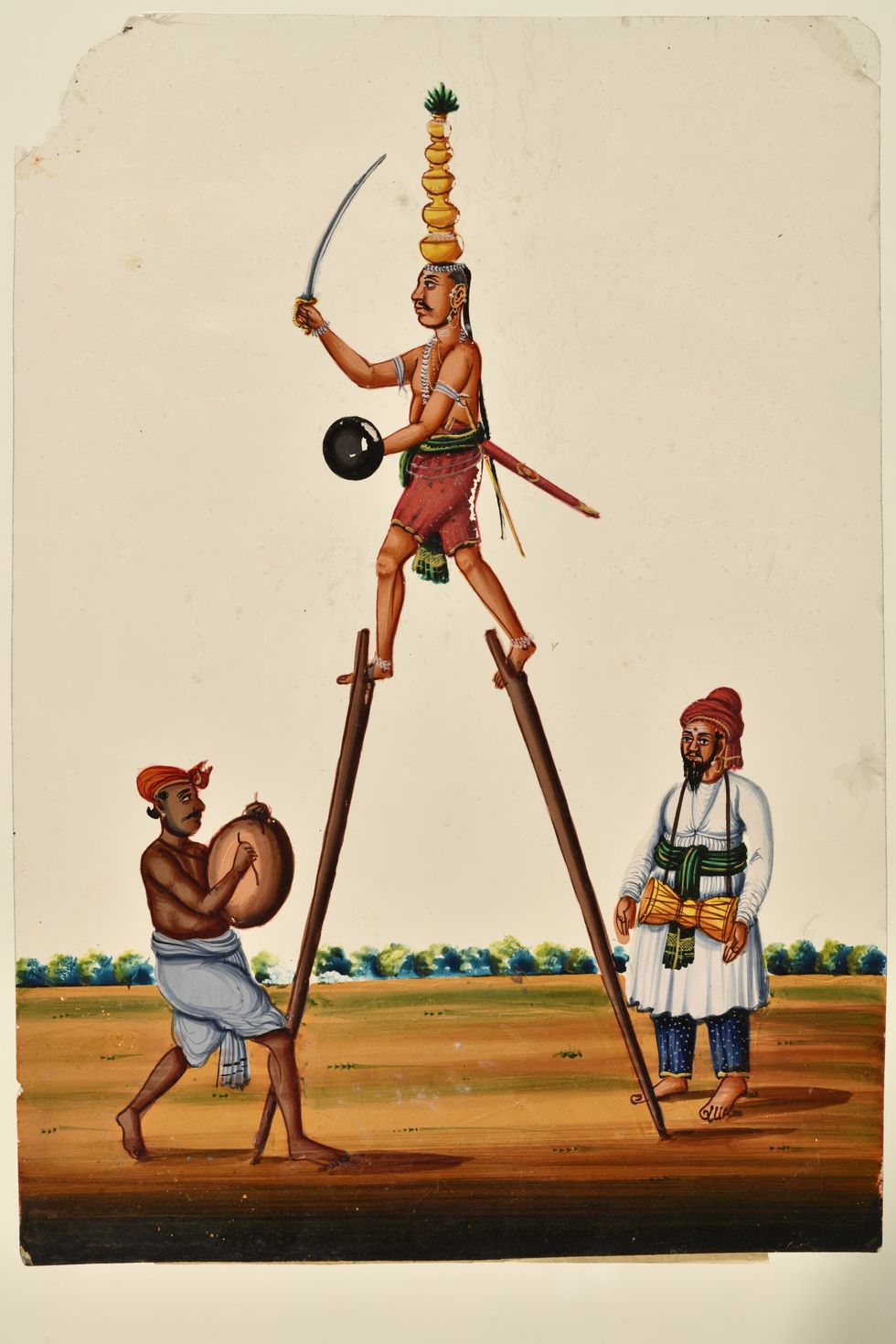

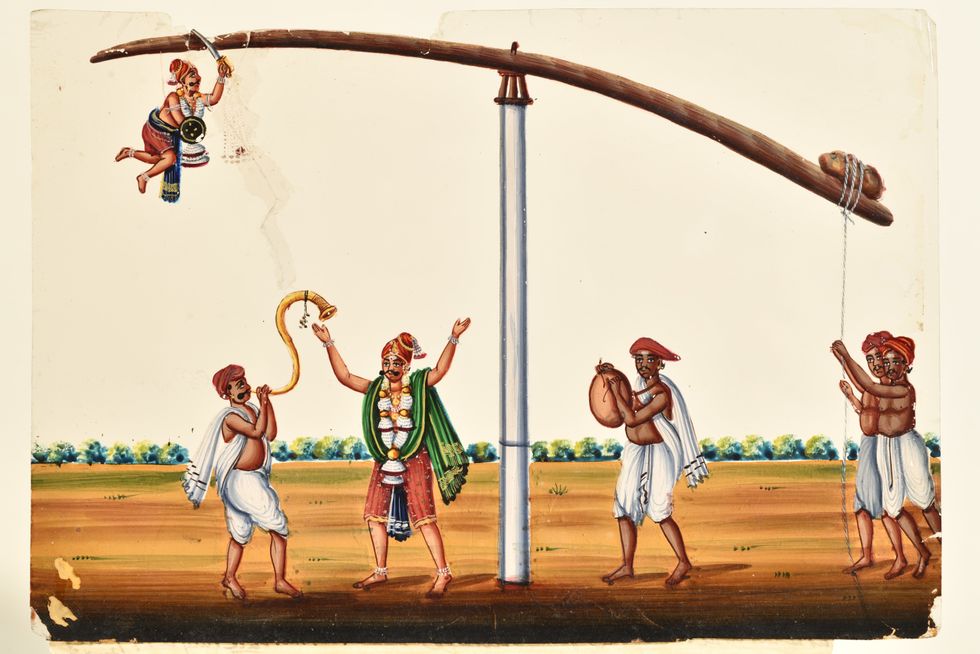

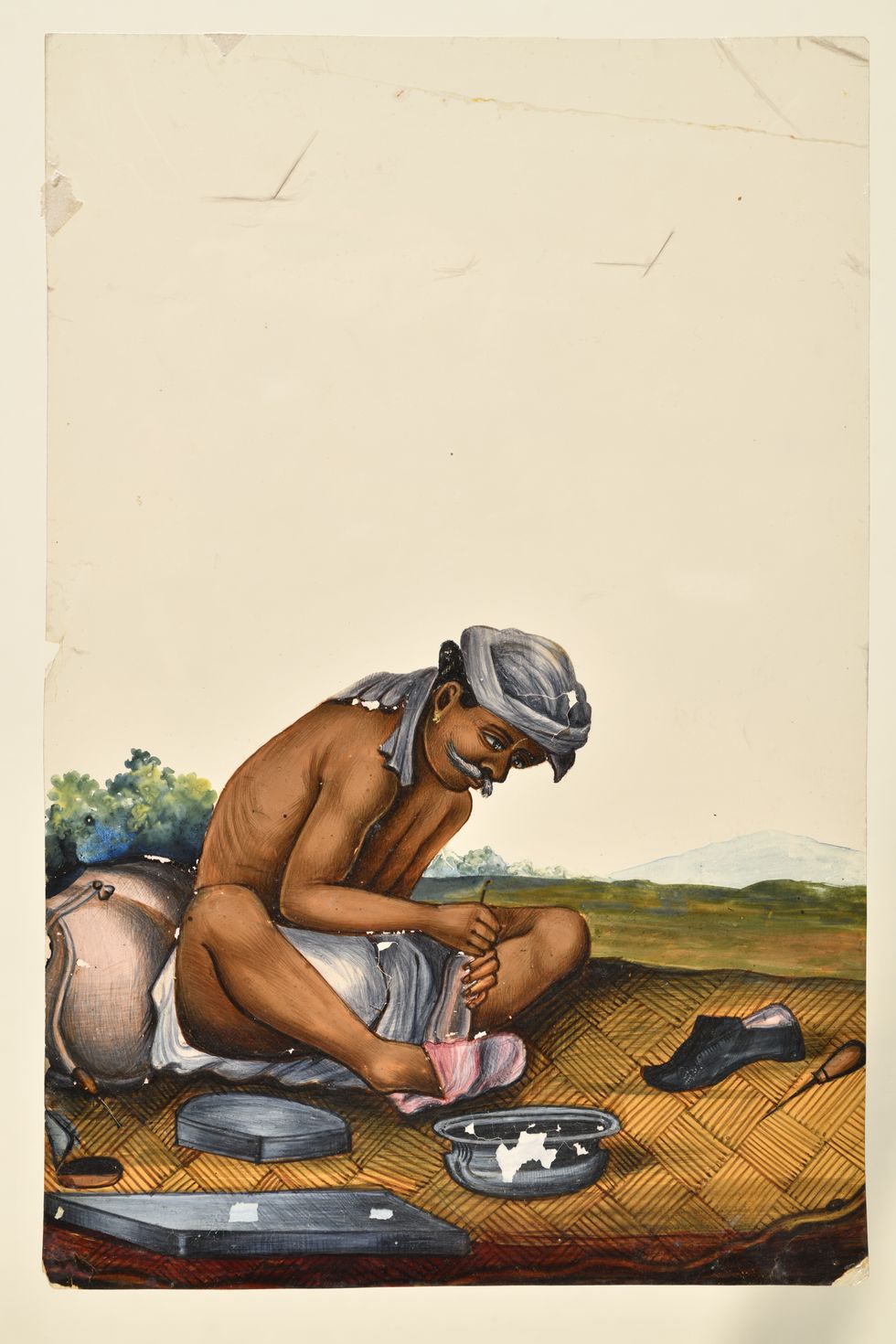

Vira, who was assisted by her son, Shauryya Vira – he is credited as co-author – says: “The focus shifted from court scenes to daily life, to bazaar scenes, to the spice seller, the vegetable seller, their customs and costumes. They have barbers, snake charmers. Often just one person. The trades people are called firka. The firka albums are really, really fascinating, because they were always done in couples: man and woman. It was also about daily life as the country was hurtling through colonisation.

“What developed is a unique style: Indian techniques and colours under European influence. You can also see regional differences between north and south. A network of cities became centres of art – Patna, Murshidabad, Benares (Varanasi) in the north, and Tiruchirappalli and a couple of other places in the south. Suttee (burning of widows) is depicted. Artists depicted what they saw in daily life. The British were appalled and fascinated in equal measures.”

Vira found the mica paintings in private collections.

“There is nothing in this book which is from a museum either in India or in Britain. Collectors were very generous to me, but asked not to be identified. All the pictures in the book have been taken by Amit Pasricha, who is one of India’s top photographers.”

Vira went to St Stephen’s College in Delhi where she read English literature.

“I then did my MBA from the Indian Institute of Foreign Trade. Then I got a full scholarship to the London School of Economics where I did my MSc.”

Writing Art Under the Indian Sun “was like a jigsaw puzzle that I had to put together. It started when I was walking round in shops finding these paintings. There was a network of people who shared similar interests and exchanged information. Very soon, it became an obsession. If you find one painting, you look for complementary ones. If you find a ghora (horse), you look for the camel driver, and then the elephant guy. A collection evolves over time. It’s the quest, the journey. This art speaks to me.”

Art Under the Indian Sun: Evolution of Artistic Themes in the British Period by Ratna Vira and Shauryya Vira is at Shapero Rare Books, 94 Bond Street, London.