Birthday special to celebrate the impactful career of a legendary star

This week sees Dharmendra turn a year older and celebrate his 87th birthday on December 8.

The legendary actor made his film debut 62 years ago with 1960 classic Dil Bhi Tera Hum Bhi Tere and has starred in over 300 films since then. Still going strong, he will next be seen in forthcoming film Rocky Aur Rani Ki Prem Kahani, with Ranveer Singh, Alia Bhatt, Jaya Bachchan and Shabana Azmi.

Although he is best known for an impressive body of work that includes all-time classics like record-breaking curry western Sholay, and for being part of a famous family that includes Hema Malini, Sunny Deol, and Bobby Deol, the cinema great also made the Bollywood hero sexier with two iconic film scenes in 1966.

Both improvised movie moments early in his career changed Indian cinema forever. To mark the actor, described by Madhuri Dixit as the most handsome man she has ever seen on screen, turning a year older, Eastern Eye looked at how Dharmendra made a transformative move, which is still felt today, nearly 60 years after it happened.

The archetypal Hindi film hero from the early days of cinema were the well-polished, clean-cut, the boy next door types you could bring home to meet the parents. Even when these heroes played grey-shaded characters, they had vulnerability and not that explosive sex-appeal that would ignite any kind of passion, from the 1920s through till the 1950s.

In the 1940s, square-jawed movie icon Ashok Kumar would introduce a slight danger element by playing anti-heroes and Shammi Kapoor gave Bollywood a hip-shaking rock ‘n’ roll swagger with his Elvis Presley inspired look, and personality. Meanwhile, the leading ladies were breaking conservative boundaries, with figure hugging outfits, sensual dance numbers, and western-inspired looks.

Although well groomed, something was still missing from the Hindi film hero. Also, there were still very strict censor laws that had banned kissing and any kind of on-screen passion.

Conservative constraints couldn’t stop a new generation from being inspired and drawn towards the bright lights of Hindi cinema. This included a young man named Dharam Singh Deol, who was growing up in the rugged surroundings of a small village and would travel long distances to watch movies. He would win a national talent contest, with the prize being a starring role in a movie. Although that movie was never made, he made his debut with Dil Bhi Tera Hum Bhi Tere (1960), and it was immediately apparent the more muscular actor was different to other leading men.

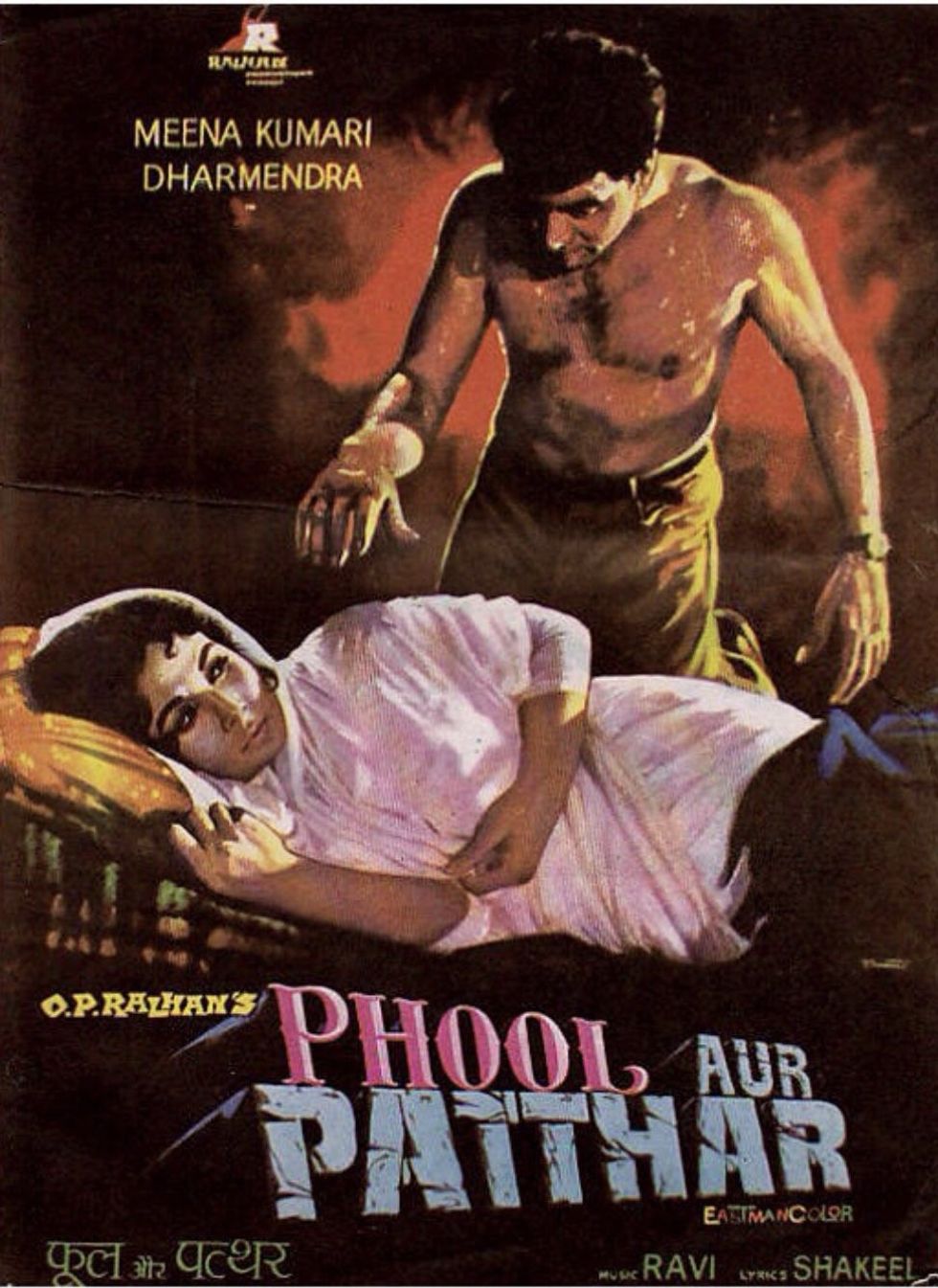

The good-looking newcomer made his presence felt in the first half of the 1960s, but was overshadowed by the older matinee idols, so very little was expected when he signed up to star in Phool Aur Patthar (1966), headlined by established actress Meena Kumari.

He played a career criminal who rescues a kind-hearted widow, in the story of opposites having a positive effect on one another, but it was two scenes in quick succession that changed everything. While going home, his intoxicated character, Shaka, spots an elderly woman asleep on the roadside late at night. He takes off his shirt and puts it over her as a blanket.

“I had said to the director, why don’t I take off my shirt and put it over the beggar on the street, to show how much of a good man he is inside (despite being intoxicated and a career criminal). How much love he has inside him. The director said you have made my scene. Then after playing with a dog on the street, he enters the bedroom bare-bodied, where the widow is sleeping. He puts a blanket on her and goes to sleep on the balcony alone,” recalled Dharmendra.

Although it is tame by today’s standard, that moment of him taking off his shirt on the street and then entering a bedroom bare bodied was breathtakingly brave for that era. The improvised scenes of him taking off his shirt and revealing a chiselled physique sent shockwaves through Hindi cinema. No frontline male star previously had the courage or muscular body to do that. For the first time, a half-naked man was seen on a commercial movie poster. It was such a big moment that a bare-bodied Dharmendra made it onto the movie poster.

The movie received a wonderful reception at the premiere, especially from female audiences, and director OP Ralhan was so happy he kissed his leading man on the cheek in front of everyone. The blockbuster hit became the highest grossing movie of 1966, largely thanks to females flocking to see the topless star on the big screen. This not only made the Hindi film hero sexier, but made producers realise they had to cater to females, who often made up more than half of audiences.

“People would call me Shaka for four to five years after the film released. He became a big craze. People started calling me names like He-man. Some said gharam Dharam and hot. I didn’t know about these things and didn’t take it seriously. I had come from a village, so part of me thought they are not serious.”

The handsome actor showed he had a body to back up his good looks and became a craze. He introduced the kind of raw, real ruggedness that had been missing. There was now an alternative option to the well-manicured, clean-cut idols that had dominated Hindi cinema for decades. His hotness also didn’t go unnoticed by leading ladies. Sharmila Tagore recalled. “Dharmendra was very hot and was a pal. Dharmendra was really sweet and respectful.”

That ruggedness would define the 1970s, with heroes having stubble, unkept hair, and showing off more of their body, like the hairy chest. But only Dharmendra had the body and sex appeal to regularly appear shirtless in films like Dharam Veer, and often in tiny shorts to show off his muscular legs.

Heroes also knew they couldn’t get away with being overweight and became more conscious of staying in shape, thanks to Dharmendra. But it wouldn’t be until the late 1980s that leading men caught up with him in terms of muscles, with actors like Salman Khan, who described Dharmendra as the most beautiful looking man, showing off a gym honed body. Super model turned actor Arjun Rampal, who described him as the most handsome man, would follow in his footsteps in terms of physique.

Fast forward to the present and more leading men than ever unveil six-packs, muscles, and a raw sensuality. But it all started with Dharmendra’s improvised scene that made heroes sexier. This not only captivated audiences, but Bollywood’s undisputed queen of the 1970s, Hema Malini, who said: “Dharmendra is definitely the most handsome man I’ve ever met. That is why I married him.”