NAGA MUNCHETTY should feel secretly pleased that after Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, she has become the number one hate figure in the media, especially for white women feature writers who earn less than her £360,000.

Naga apparently gets cross with junior staff who don’t do her toast right – it apparently has to be burnt the way she likes it.

Naga, a presenter on BBC Breakfast, is accused, among other things, of bullying staff. If her critics have their way, she will soon be toast herself.

Last week, following the resignation of Rushanara Ali as a junior housing minister, I drew attention to other Asian women politicians – among them Tulip Siddiq, Suella Braverman, Priti Patel, Baroness Pola Uddin and Rupa Huq – who have got into trouble for one reason or another.

Is something similar happening in the media?

Apart from Naga, I can think of other Asian women journalists in television or radio who have not seen eye to eye with the employers.

I will come to the others – Mishal Husain, Sangita Myska, Ritula Shah and Lisa Aziz – but Naga first.

Annabel Denham, columnist and deputy comment editor in the Daily Telegraph, had a piece, “It’s not easy to defend Naga Munchetty, but workplace wokery is out of control”, which said: “This generously paid cultural arbiter once called Boris Johnson a ‘useless tosser’, liked disparaging tweets about Robert Jenrick and bizarrely scolded Kemi Badenoch for failing to watch that tendentious Adolescence series – prompting the Tory leader to reply, rather neatly: ‘In the same way that I don’t need to watch Casualty to know what’s going on in the NHS, I don’t need to watch a Netflix drama to understand what’s going on.’

” Her colleague, Liam Kelly, wrote: “Her on-air behaviour has also occasionally caused controversy. She was censured in 2019 for criticising Donald Trump for telling a group of non-white Democrat congresswomen to ‘go back’ to their ‘crime-infested’ countries. ‘Every time I have been told, as a woman of colour, to go back to where I came from, that was embedded in racism,’ she said live on BBC Breakfast, before later adding that she was ‘absolutely furious’ about the US president’s comments.

“The Corporation partially upheld a complaint that her remarks had breached editorial guidelines before Tony Hall, then the directorgeneral, intervened to reverse that decision. Some two years later, Munchetty apologised after liking ‘offensive’ tweets that disparaged Robert Jenrick, then the housing secretary, for being interviewed on Breakfast with a large Union Flag and a portrait of the late Queen behind him.”

Pointing out she tied for 11th place on the BBC’s high pay list, Kelly added: “It is a far cry from her childhood growing up in Streatham, south London. Her Indian mother, Muthu, and Mauritian father, David, moved to Britain in the 1970s and worked as nurses while they brought up Munchetty and her younger sister, Mimi.”

Mishal Husain left the BBC earlier this year for Bloomberg TV after 11 years as a presenter on Radio 4’s flagship Today programme.This was after Andrew Marr was replaced by Laura Kuenssberg as presenter of the Sunday morning politics slot.

Last year, LBC removed Sangita Myska as a presenter after she was a little too robust in questioning the Israeli government spokesman, Avi Hyman.

In 2000, Samira Ahmed took the BBC to an employment tribunal, after protesting she was paid £440 for Newswatch, which is shown on the BBC News Channel and BBC Breakfast. But Jeremy Vine was getting £3,000 per episode for the similar BBC One’s Points of View. The tribunal agreed with Samira: “The difference in pay in this case is striking. Jeremy Vine was paid more than six times what the claimant was paid for doing the same work as her.”

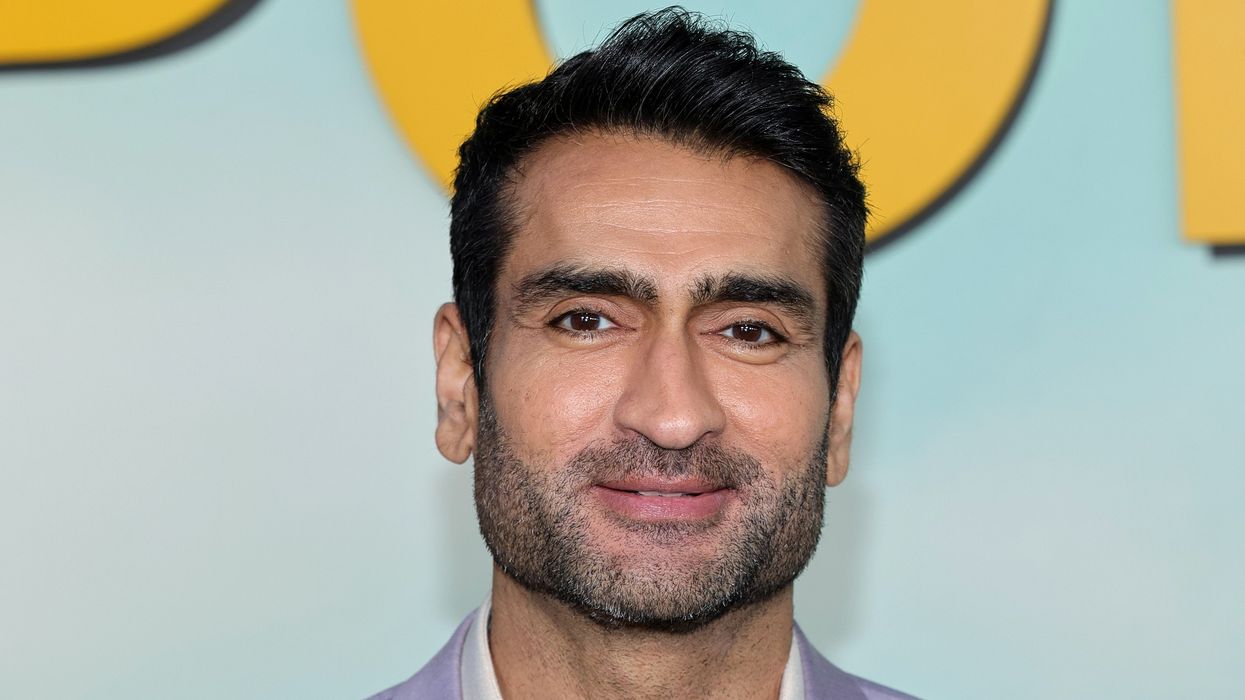

In 2023, Ritula Shah left the BBC after 35 years, having been lead presenter of the World Tonight on Radio 4 since 2013. She said she was upset to discover she was being paid tens of thousands of pounds fewer than her male colleagues. She now has a late night slot on Classic FM, but misses the urgency of current affairs: “It’s a really painful episode in my life and I still can’t quite get over it, even though it’s now behind me.”

Liza Aziz, once the glamour girl among TV presenters, joined ITV in 2006 after 10 years with Sky News. But after four years she fell out with ITV West in Bristol after her employers accused her of financial irregularities and she considered taking legal action for race, sex and age discrimination. Lisa left after a settlement was reached.

Each case is different, and I am not taking sides. But Asian women with high profile jobs in the media have to be extra careful about not giving offence. Quite often in order to fit in, they have to buy a bottle of wine to share with their male white colleagues after work. In the workplace culture, they have to go with the flow.

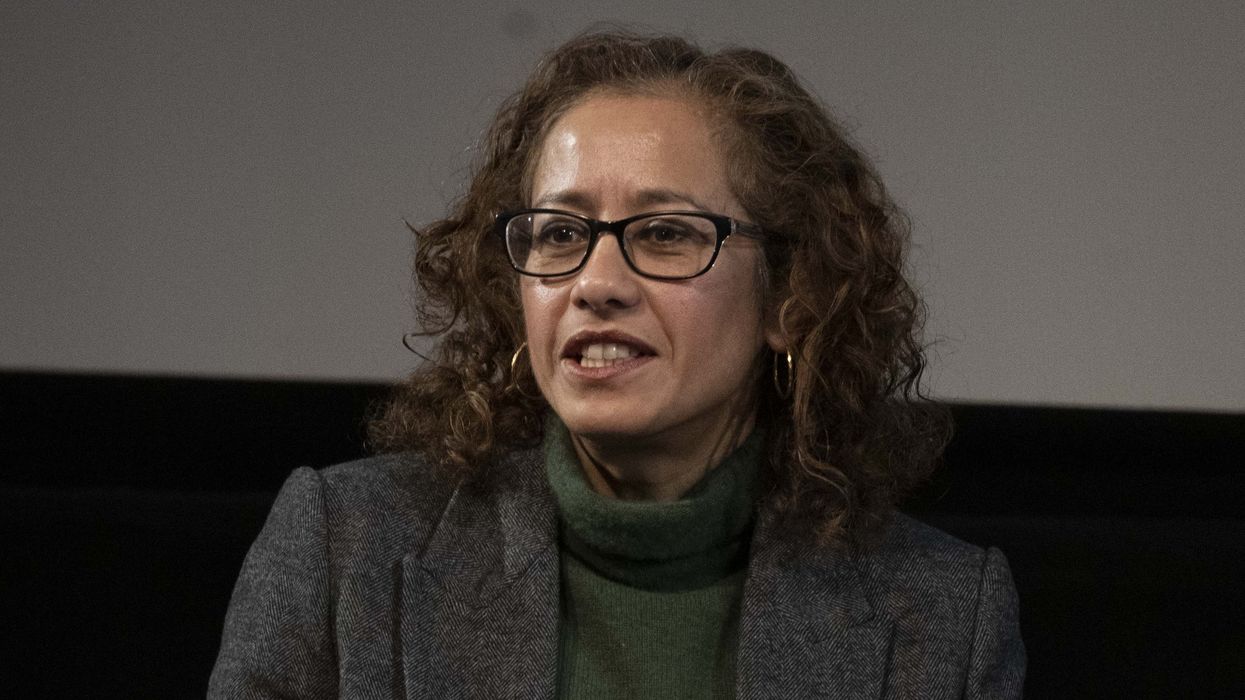

Sheela Banerjee, author of What’s in a Name? Friendship, Identity and History in Modern Multicultural Britain, told Eastern Eye a couple years ago when her book came out: “I gave up TV. As a state school educated, nonOxbridge, brown woman, it is hard. There are not that many of us. If you were trying to make documentaries, it was virtually impossible. We’d get shunted off into light entertainment and stuff like that. Which is fine. But that’s not what I wanted to do. And also, it’s just rife with discrimination. That’s the problem. And it’s really stressful. It’s still the same.”

She quoted some diversity figures from television. “The number of black, Asian and minority ethnic directors in factual television in 2018 – not that long ago – was like three per cent. I mean it’s absurd. And most of the productions are in London or Manchester, hugely diverse cities. And most programmes are now made by independent production companies, even for the BBC. If you go on to their websites and then ‘meet the team’ pages, there’s a sea of Hannahs and Lucys and Elsas and Charlottes. It makes me so angry. There are lots of industries that are exactly the same – for example, academia and publishing. But television is still really important because lots of people watch it and get their information from it.”

Ritula Shah

Ritula Shah