PRAYERS by representatives of the Hindu and Jain faiths, followed by Buddhist incantations, echoed through the Norman Foster-designed two-acre Great Court at the British Museum last Monday (19).

The occasion was a significant and auspicious one for Eastern Eye readers and the wider British Asian community – the opening of the British Museum’s landmark exhibition, Ancient India: Living traditions.

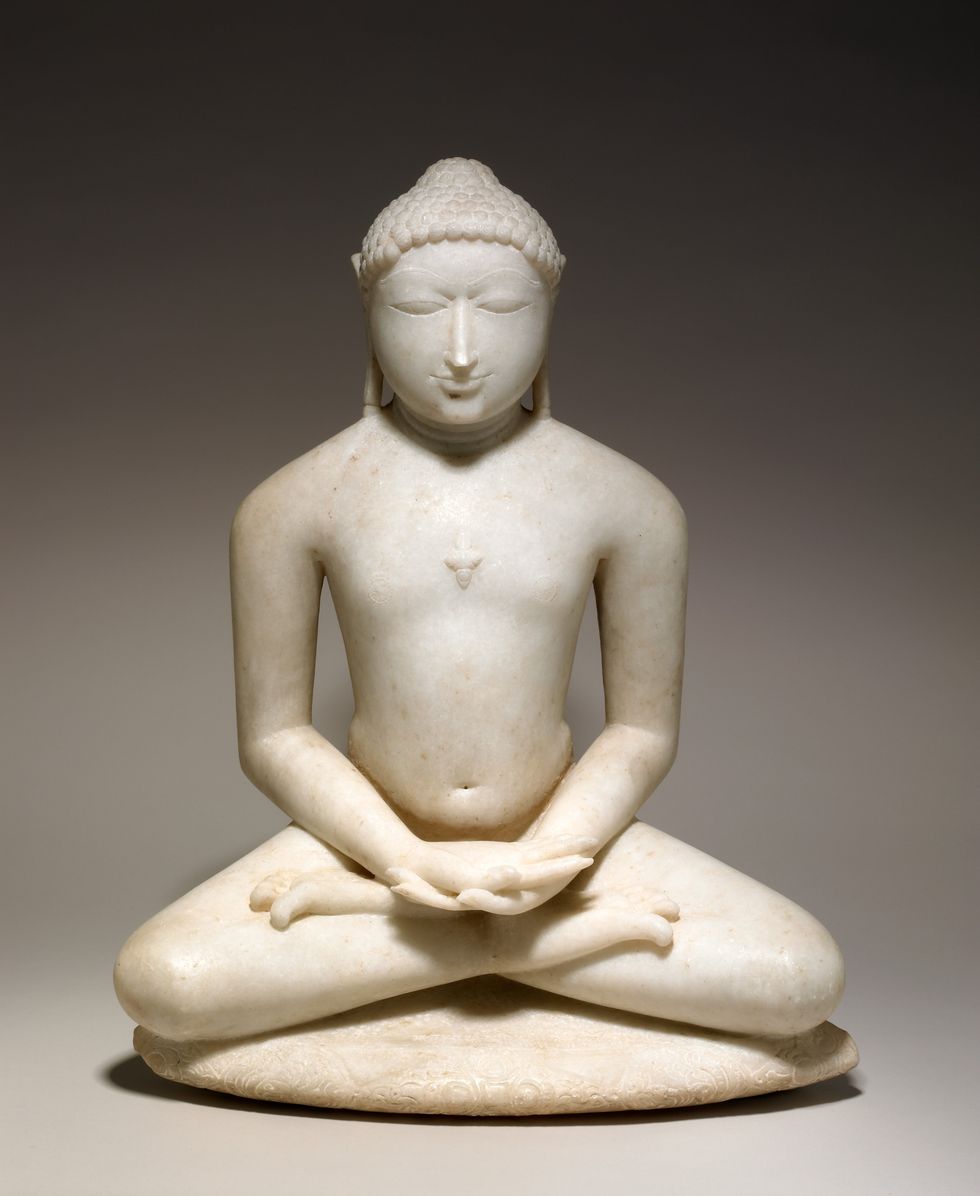

Curated by Dr Sushma Jansari, head of the British Museum’s south Asia department, the exhibition looks at how Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism influenced each other over a 600-year period of Indian history.

The Buddhist incantations of monks from the Buddhapadipa temple in Wimbledon followed prayers offered by Kirtan Patel, cultural engagement volunteer at the BAPS Swaminarayan Mandir in Neasden, north London, and Jayeshbhai Shah, a priest from the Oshwal Association of the UK in Potter’s Bar in Hertfordshire.

George Osborne, chairman of the trustees at the British Museum and chancellor of the exchequer when David Cameron was prime minister, said: “Compared with these religious traditions, the 250-yearhistory of the British Museum, this temple of enlightenment, is relatively short.”

He quipped: “We probably never had an exhibition blessed before in quite that way by three different religious traditions.”

Standing at the podium in front of a poster featuring the elephant-headed Hindu deity, Ganesh, he said: “Everyone who ever speaks from this podium complains about the acoustics in the hall, but I think it was designed for a wonderful kind of echoing of the chanting.”

He said the curator and her team had taken some difficult decisions in not doing the exhibition in a traditional manner. Osborne was referring to the way in which the story of the three faiths was shown.

“They’ve tackled this 600-year period of Indian history not in a boring, straightforward, chronological way, which museums have done before.

“Instead, it plunged into this very complicated story of three different religious traditions and how they emerged, how they interacted with each other at this crucial period of Indian history – this was a difficult exhibition to create and conceive.”

Osborne pointed out that the British Museum “is famous is for its monumental sculptures from India and Egypt and the near East and so on. And, yet, this show is all about the personal. It’s all about trying to connect with what people thought, believed, and what was intimate to them 2,000 years ago.

“And again, this is a museum that is trying to introduce new audiences to our collection and the collections that we draw on from around the world, and make that human connection to people.”

He stressed: “The clue is in the name of the exhibition. We are not just a museum of the past, and not just a museum of relics, of dead traditions, of dead empires, things that have gone before us. There is a deliberate effort here, in this show, as indeed in many other things, to connect to the today and to the future.

“These great religious traditions are followed by many billions of people in the world today. And that, again, is something we’ve deliberately chosen to do. It’s something it would be easier to stay out of. And a lot of people would say, ‘Let’s not talk about religion. Let’s back off.’ And we stepped forward. That shows that the British Museum is really at the top of its game at the moment.

“What you’ll see in this show is a lesson in collaboration – collaboration with religious communities, collaboration with museums in the Indian subcontinent and beyond that. And it shows us doing what I think we were supposed to do, which is draw people through these doors, and hopefully when they leave, they know a bit more about the world, they understand a bit more about the world and they’re a bit more sympathetic to the world.”

The British Museum’s director, Nicholas Cullinan, explained: “The visual traditions of ancient India were adopted and adapted to new settings and cultures. And, of course, this exchange was never one way. As these traditions spread (to south-east Asia, China, Japan and other parts of the world), they encountered and absorbed local influences, creating rich artistic dialogues and images that can still be traced in the objects on display. In doing so, they helped to shape religious life in many parts of the world, creating shared visual languages that connect to distant communities across oceans and continents, as they still do today.

“This is not just an exhibition about the past. These living traditions and the art objects on display are as relevant and meaningful today as they were when they were first made. This exhibition has been developed in close collaboration with members of practising Hindu, Buddhist and Jain communities (in the UK). I’d like to express my sincere thanks to the members of our community advisory panel who generously shared their knowledge, insight and perspectives throughout the development of the exhibition. Their voices are woven into the exhibition and have shaped how we present powerful works to new audiences.

“We’re also deeply grateful to our lending partners who have made this extension possible, and, foremost among them, is the CSMVS Museum (Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, formerly the Prince of Wales Museum) in Mumbai, the National Museum of New Delhi and many other global and national partners. Their generosity has enabled us to gather more than 118 exceptional objects, each with its own story.

“Of course, I’d like to express particular appreciation to Dr Sushma Jansari, the curator of this exhibition. Her expertise, commitment and vision have guided this project from the early stages to the extraordinary experience you’ll have this evening.

“In a time where we’re often focused on division, I think this exhibition reminds us of our shared narrative, the real desire to seek meaning in our lives, to create beauty and to honour something that is far greater than ourselves.

“These works are not just relics or sculptures. They are real and genuine expressions of devotion, compassion, creativity and connection. They are reminders of this common heritage that crosses time, languages, belief and nations, and so I hope you will find joy and wonderful inspiration in this exhibition, and leave with a deeper appreciation of the truly extraordinary cultures that created them and have shared them in the world.”