WHO were the first Asian faces that you remember featuring regularly on television?

Beyond the specialist Asian community programmes on a Sunday morning, there were pretty slim pickings across the ‘eighties. The Eastenders portrayal of everyday East London life would depict one Asian family at a time in Albert Square, juggling minding the shop with family tensions over arranged marriages. There were Madhur Jaffrey’s curries, historical dramas set in the days of the Raj, and stereotyped bit parts in sitcoms until Goodness Gracious Me changed the game, very late in the century. The sprinkling of pioneering British Asian journalists and newsreaders of the 1990s – on the BBC, Channel 4 and regional news programmes – were a memorable and scarce presence.

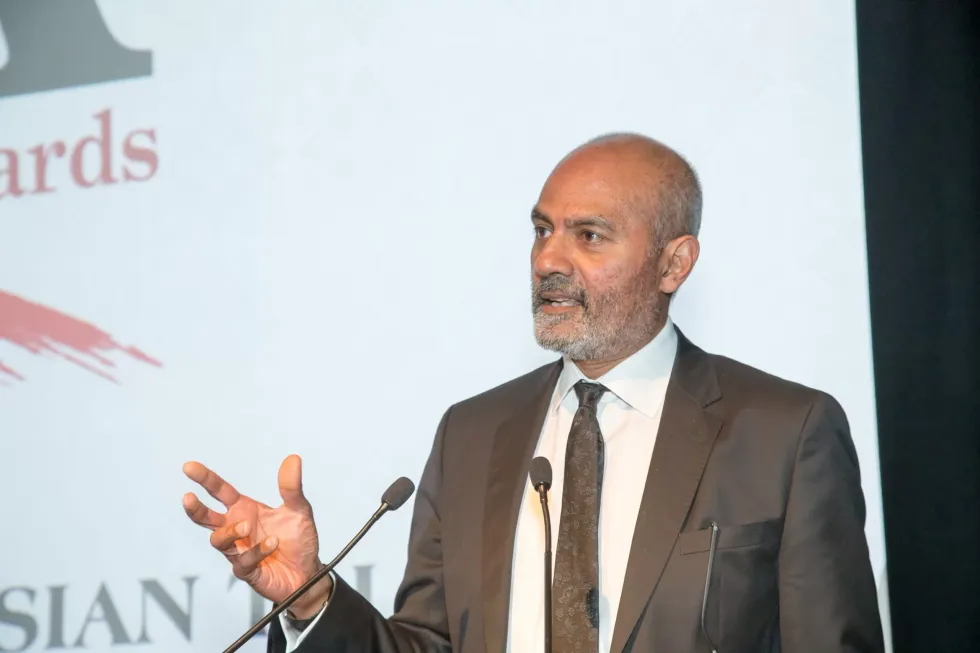

One recurring theme of the tributes paid to George Alagiah, after his death from cancer was announced last week, was how the inspiration of his on-screen presence was combined with such kindness and support to those who came after him. Alagiah found it surprising, at first, to find his personal and professional success celebrated by others, but came to embrace it. “I came to realise that, whatever I have done, I have also achieved it for communities that I never thought I represented,” he told an Eastern Eye awards ceremony a few years ago.

Alagiah was twice a migrant, with his family leaving Sri Lanka for Ghana when he was six, before coming to boarding school in England as an 11 year old. “We did not come here empty-handed. We brought with us our varied talents and our capacity for hard work,” he was often to say.

If he always saw integration as foundational, his views about how best to pursue it shifted over time. His 2006 memoir A Home from Home: from immigrant boy to English man described the initial compulsion to assimilate – for ‘total immersion’ – as partly about self-preservation, even if not standing out meant pretending to laugh along with the racist jokes at school.

“It was only when I was secure in what I had become that I could explore what I had been,” he wrote. Alagiah was primarily an optimist about Britain – reflecting his experience of a Britain that was a land of possibility and opportunity. That confidence was significantly shaken by the 7/7 bombings, as he became sharply critical of forms of multiculturalism in which recognising diversity tipped over into an official indifference to social segregation, and too little interest in fostering the common bonds of a multi-ethnic shared Britishness.

Alagiah celebrated too, in his ground-breaking Mixed Britannia television series, that this is “one of the most mixed countries on earth”. Yet he came to worry, especially after his father’s death, about whether he and his sons – “as British as they come” – might become untethered from the family’s journey of migration. Integration could involve a sense of loss too.

Alagiah became a champion of the need for a modern British story: “the story of the making of a United Kingdom of people, both of those who are British by birth and British by choice.” He became an advocate for a national Migration Museum, and a trustee of the successful effort to bring it to fruition.

“Stories to tell” is the theme of South Asian Heritage Month, now in its fourth year and gradually establishing itself as a fixture in the heritage events calendar. The 18th July to 17th August dates of South Asian Heritage Month map the dates in 1947 from the Royal Assent to the Indian Independence Act through to the anniversary of Partition. Those dates capture how much influence the British had on modern South Asian history. There is no single, symbolic ‘origins moment’ of the South Asian presence in Britain, which stretches back four centuries, but those dates capture too how much the language of modern British Asian identity ‘over here’ was shaped primarily by the post-partition national identities of the sub-continent -– Indian and Pakistani, later Sri Lankan and Bangladeshi too – over there.

A wide range of different events are taking place across the month. I took part in a Warner Music panel, compered by broadcaster Nihal Arthanayake, which included Professor Tariq Jazeel explaining the history of prejudice and racial slurs, which indiscriminately lumped all Asians together. South Asians would be, by some distance, the largest ethnic minority group in the country – one-tenth of those living in England and Wales – if they are still considered to make up a single group. One outcome of the progress that we have made across the generations is that the internal pluralism and diversity within the group is more recognised too.

This would have been welcomed by Alagiah, who emphasised the importance of ensuring that all of the stories of the making of modern Britain could be told. He argued that what mattered most was to join the dots: to “stitch all the myriad migrant contributions into the fabric of the story we tell ourselves about who we are”. His own part in that story will not be forgotten.

George Alagiah and the story of who we are today

Alagiah was a champion of the need for a modern British story, says the expert