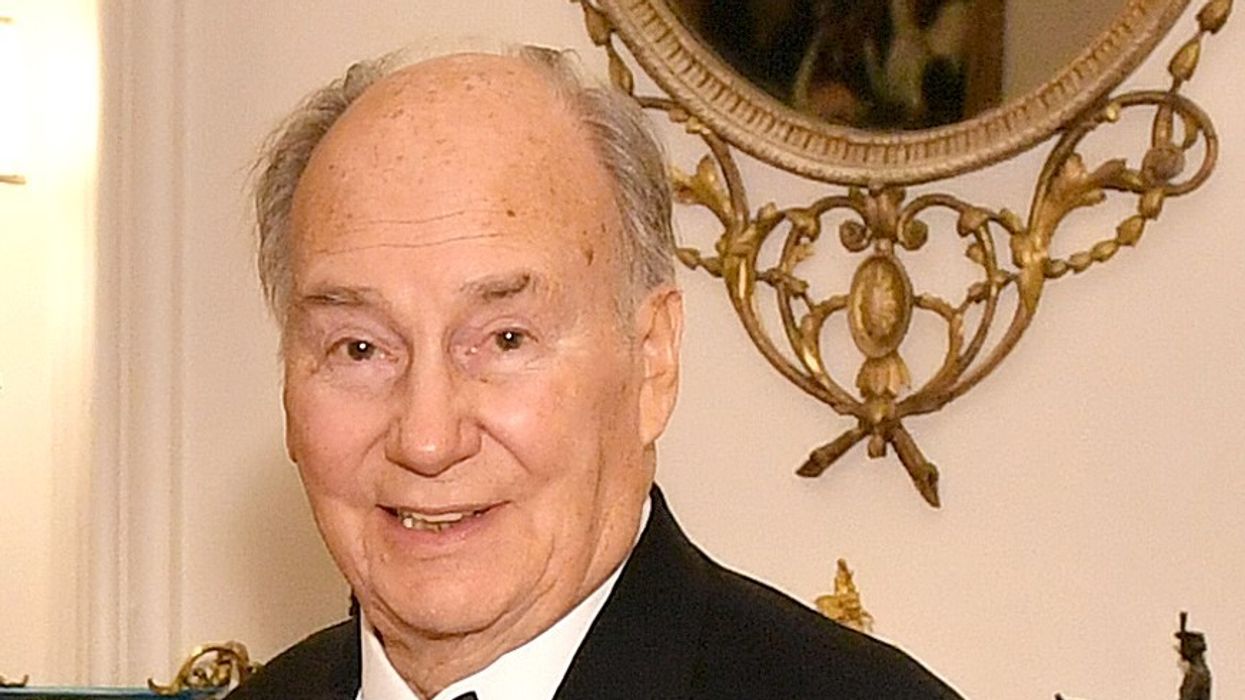

THE late Prince Karim Aga Khan IV, who passed away in Lisbon last month, succeeded his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan 111, as the spiritual leader of the Shia Imami Ismaili Muslims in July 1957, when massive changes were taking place globally.

Having taken a year off from his studies at Harvard University, the Aga Khan IV decided to travel all over the world to gain a first-hand understanding of his followers’ needs and what would be required to ensure quality of life for them and the people among whom they lived, regardless of race, faith, gender or ethnicity.

On a visit to Hunza, on the border of Afghanistan and the People’s Republic of China, he undertook part of the journey on a donkey.

While trying to visualise programmes for the betterment of his followers he also reflected on the wide range of interventions needed to mitigate conflict and also improve the quality of life for people.

In east Africa, the Aga Khan IV upgraded education, health and economic development institutions pioneered by his grandfather under the old colonial system and provided them a meaningful role in nation-building activities as the countries in the region prepared for political independence.

Here, he understood the plight of the indigenous African people and while guiding his own community to prepare for the new reality of independence, he also founded the first African owned newspaper, the Nation Group, that would go on to lay the foundation of a responsible press in east Africa.

This eventually went on to spawn the Graduate School of Media and Communications of the Aga Khan University which he established; today it has faculties in six countries, spanning east Africa, south Asia and the UK.

The Aga Khan IV was involved in a range of activities globally, which included education, healthcare, low cost housing, micro finance, cultural regeneration programmes, energy development, rural support programmes, architecture, industrial development and eco-tourism.

He set up one of the most prestigious prizes in the world, The Aga Khan Award for Architecture, which recognised excellence in the sector, while engaging people from different disciplines. That award led to the setting up of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, which today is responsible for a number of restoration projects in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Egypt, Uzbekistan, Spain as well as Canada.

In the field of rural development, he founded the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) in northern Pakistan with Shoaib Sultan Khan, a protégé of the world renowned expert, Akhtar Hamid Khan. It became a model of a people-centric process which today is emulated in many parts of the world including the high mountain valleys of central Asia.

The Aga Khan IV’s greatest strength was his ability to listen to the needs of the people at the grassroots level and his readiness to consult. He believed that people were the best agents of their own transformation and was able to tap the talent of some of the best brains in the world.

A man of great humility, he shied away from praise. When asked by a leading Canadian TV journalists, (the late) Roy Bonisteel, how he would be liked to be remembered one day, the Aga Khan’s answer was a very categorical “not by name or by face”. If his programmes to help the people they were meant to serve actually reached them, then his mission in life would have been fulfilled, was his response.

A pluralist by nature, the Aga Khan had a deep understanding of the pathology of conflict. He set up a Global Centre for Pluralism in partnership with the Canadian government to study conflict and the pre-emptive measures to prevent it.

In every field he was involved in, he aimed for excellence, but always kept in mind that to change society one must engage people and inspire hope in them.

He was known as an institution builder and has been succeeded by his eldest son His Highness Prince Rahim Aga Khan, who spent the past two decades working by his side on the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). It is a global umbrella organisation under which all these development activities are conducted.

As the Aga Khan V, Prince Rahim is well poised to continue a legacy that goes back centuries of an Islamic dynasty that founded Cairo and gave the world one of its first universities – the Al Azhar University, over a thousand years ago. We wish Prince Rahim Aga Khan an Imamat in which he continues to serve the cause of humanity as his noble ancestors did through the AKDN and the global Ismaili community of some 15 million settled in over 35 countries of the world.

Anurag Bajpayee's Gradiant: The water company tackling a global crisis