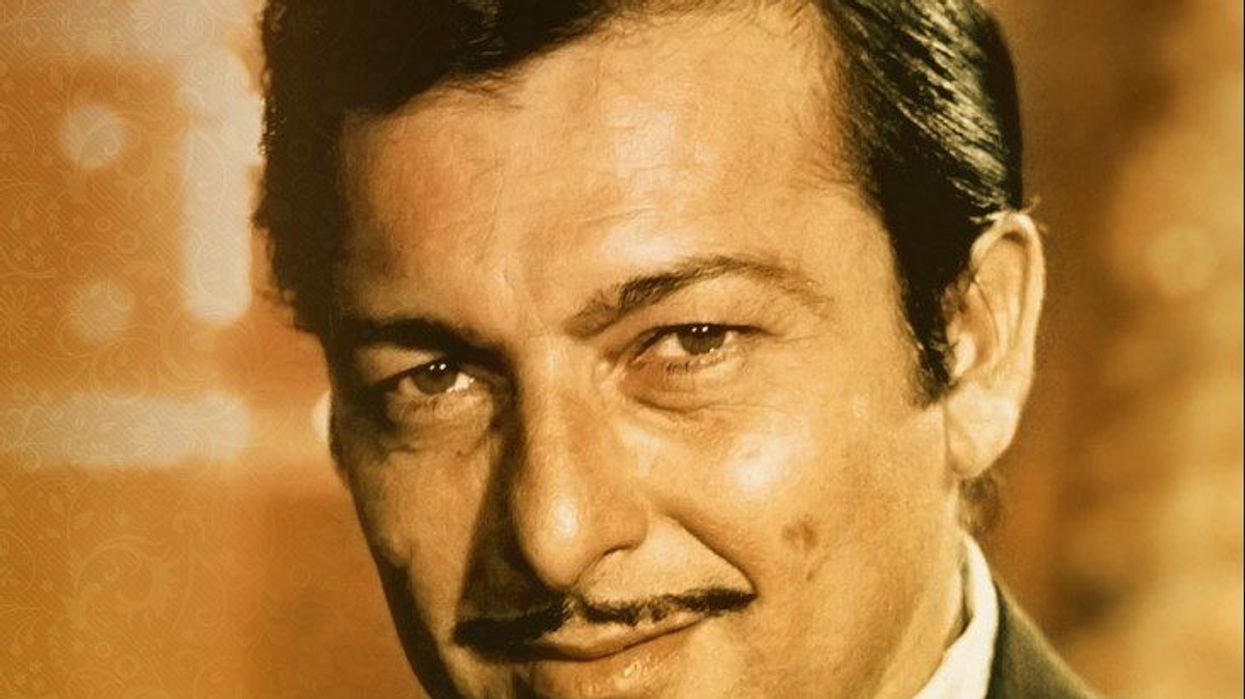

THE magnificence of master musician Madan Mohan is demonstrated by songs that remain massively popular decades after they were recorded.

Whether it was iconic love song Lag Jaa Gale in 1964 or his compositions being used on the 2004 Veer Zaara soundtrack nearly 30 years after he passed away on July 14, 1975, aged 51, he left a permanent mark on the Bollywood landscape.

Eastern Eye decided to mark his death and recent birth anniversary on June 25, 1925, by presenting an all you need to know A to Z on one of Hindi cinema’s most revered figures.

A is for Army: Madan Mohan joined the army in 1943 as a second lieutenant and served for two years until the second world war ended. His heart remained connected to music and he would organise shows for fellow soldiers. Shortly after leaving the army, he reconnected with music by joining All India Radio (see R).

B is for Beginning: The aspiring young hopeful began his professional music career by singing ghazals in 1947 and 1948. Composer Ghulam Haider gave him the opportunity to sing two duets with Lata Mangeshkar for the film Shaheed (1948), but they were never released or used in the movie. He also worked as an assistant to legendary music director SD Burman from 1946-1948.

C is for Cirrhosis: The music director went through a lot of struggles (see S), including not getting the recognition he deserved and the brutal murder of his brother, which affected him deeply. He began to drink heavily and eventually died of liver cirrhosis on July 14, 1975. The pallbearers of his body included famous actors Rajesh Khanna, Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan, and Rajendra Kumar.

E is for Escape: A few months before his passing, Mohan had a lucky escape when his car skidded off the road and was fully destroyed. He had jumped out of the car just in time. Battered and bruised, Mohan caught a taxi and went straight for a scheduled studio session because he was never late for a recording.

F is for Family: He had an arranged marriage to Sheila Dhingra, niece of the freedom fighter Madan Lal Dhingra, in January 1953. He was devoted to his wife and children, and she described him as a deeply caring family man. Speaking of family, he was left traumatised when his talented cinematographer brother Prakash Kohli was murdered on a train.

G is for Ghazals: Mohan is particularly remembered for his ghazals, or songs connected to that genre. When he passed, legendary music director Naushad said: “The king of ghazals has gone and left no peer”. Meanwhile, Lata Mangeshkar described him as the prince of ghazals.

H is for Hits: The music maestro left behind many timeless hits that include Aap Ki Nazron Ne Samjha, Lag Jaa Gale, Jhumka Gira Re, Yeh Duniya Yeh Mehfil, Dil Dhoondta Hai, Husn Hazir Hai, Ae Dil Mujhe Bata De, Sapnon Mein Agar Mere Tum Aao To, Tum Jo Mil Gaye Ho, Rasm E Ulfat Ko Nibhaaen To Nibhaaen Kaise, and many more, including the Veer Zaara soundtrack (see V).

I is for Interests: The music maestro’s biggest passion away from music was sports. He loved watching cricket, hockey, wrestling, horse racing and football. He was a good boxer and a competition winning billiards player. Mohan was also into bodybuilding and had a better physique than the Bollywood leading men of the day. He was also an excellent chess player and renowned widely for his cooking skills. He loved travelling, with the UK being a favourite destination.

J is for Jaddanbai: His earliest musical influence was Jaddanbai, who was one of the first female singers and composers in Indian cinema. He was also inspired by the vocal styles of singers Begum Akhtar and Barkat Ali Khan.

K is for Kishore Kumar: Although Mohammed Rafi was his preferred singer, Madan Mohan was good friends with Kishore Kumar and worked with him on multiple movies. One particular song he recorded with him for the film Man Mauji (1962) was banned because it was considered anti-social.

L is for Lata Mangeshkar: Mohan worked with all the major singers, but his favourite was Lata Mangeshkar and he brought out the best in her with songs like Lag Ja Gale. They shared a brother-sister bond early on and she became his biggest champion in an industry that didn’t give him his due (see S). The Nightingale carried on praising him right until her death and said he was the composer who challenged her most. She said: “Madan Mohan’s music will prevail, for it embodied melody, the basis of Indian music. It was my privilege to have sung for him.”

M is for Mohammed Rafi: His preferred male singer was Mohammed Rafi who became a muse for him. He challenged the singer to use his voice in different ways and the result was a long list of unforgettable songs, including Tum Jo Mil Gaye Ho, Kabhi Na Kabhi, Yeh Duniya Yeh Mehfil, Ab Tumhare Hawale Wattan Sathiyo, Sawan Ke Mahine Mein, Tere Dar Pa Aaya Hoon and many more.

O is for Onscreen: The dashing young man harboured dreams of becoming an actor, but that didn’t work out. His first film as a hero was shelved, shortly after shooting. He made appearances in films like Shaheed (1948), Aansoo (1953) and Munimji (1955), but they were unable to kickstart his acting career.

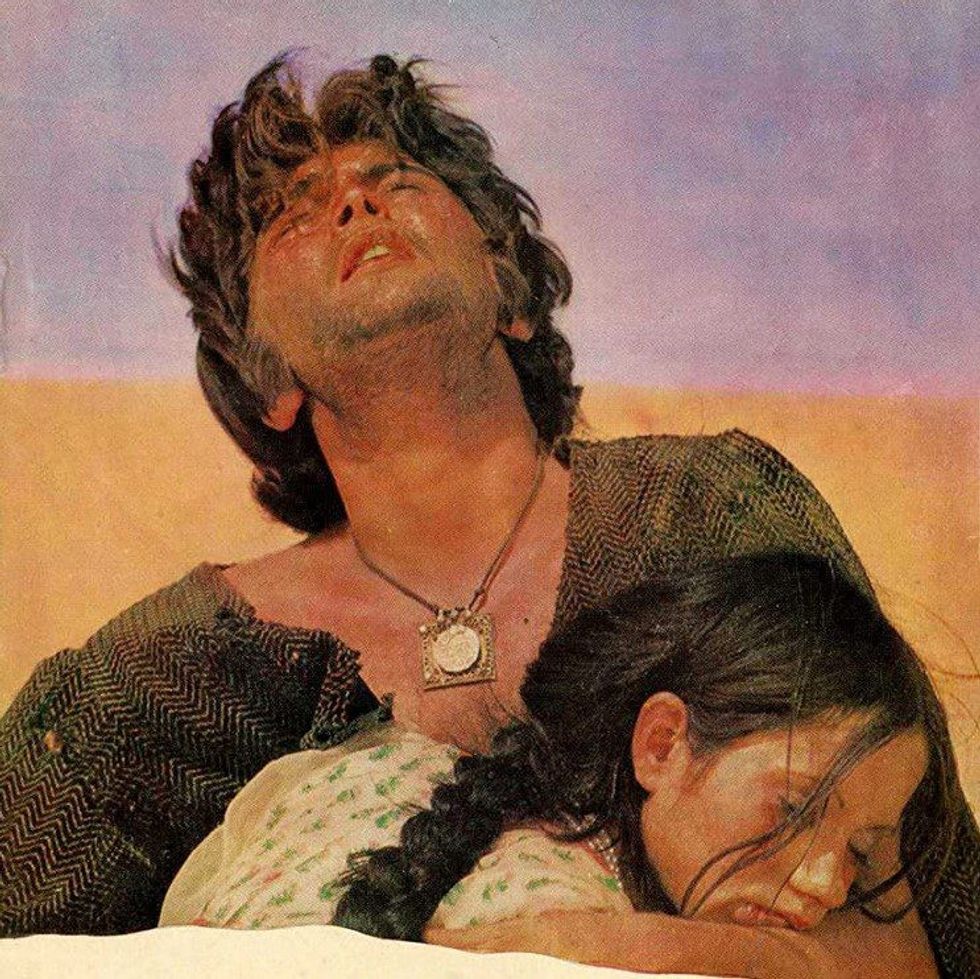

P is for Posthumous: The musician’s popularity soared after his untimely death, with many of his songs being ranked as the greatest of all time. His soundtracks for Mausam (1975) and Laila Majnu (1976) were successfully released after he died. The biggest triumph after his passing was the soundtrack for 2004 film Veer Zaara (see V). Lata Mangeshkar said some people’s horoscope opens up after they are gone, in reference to the status Mohan gained after his death.

Q is for Qawwali: For the film Jahan Ara (1964), Mohan recorded a qawwali featuring the voices of Asha Bhosle, Lata Mangeshkar, Meena Mangeshkar, and Usha Mangeshkar. It is thought to be the only song featuring the four sisters, but didn’t make it into the movie and went missing. He was still particularly proud of the soundtrack because it had a whole range of music, but the film didn’t do well, and the songs didn’t get their due.

R is for Radio: During his school days, Mohan took part in children’s programmes on All India Radio and was responsible for discovering a nine year old girl with a beautiful voice – she would grow up to become singing superstar Suraiya. Years later, after leaving the army, he returned to All India Radio. This enabled him to interact with established musicians and singers, along with composing music for programmes.

S is for Struggle: The musician’s career was defined by struggle. He was held back by rivals, who prevented him from working with bigger movie banners and getting well-deserved honours. Some would block book studios, so he couldn’t record songs. Not getting the recognition he deserved or bigger movies, despite composing masterpieces impacted his mental health.

T is for Training: Apart from a very short stint learning the basics of classical music from Shri Kartar Singh, Mohan remarkably didn’t receive any formal musical training and was largely self-taught.

U is for Unused: The music maestro may have worked on over a 100 films in a 25 year career, he had a lot of compositions that weren’t used because a movie was shelved, or songs didn’t make the final cut. While some unused songs went missing, others remained unrecorded or were never released. Some of these missing treasures were released on the album Tere Bagair, decades after his death, and others were used in the film Veer Zaara.

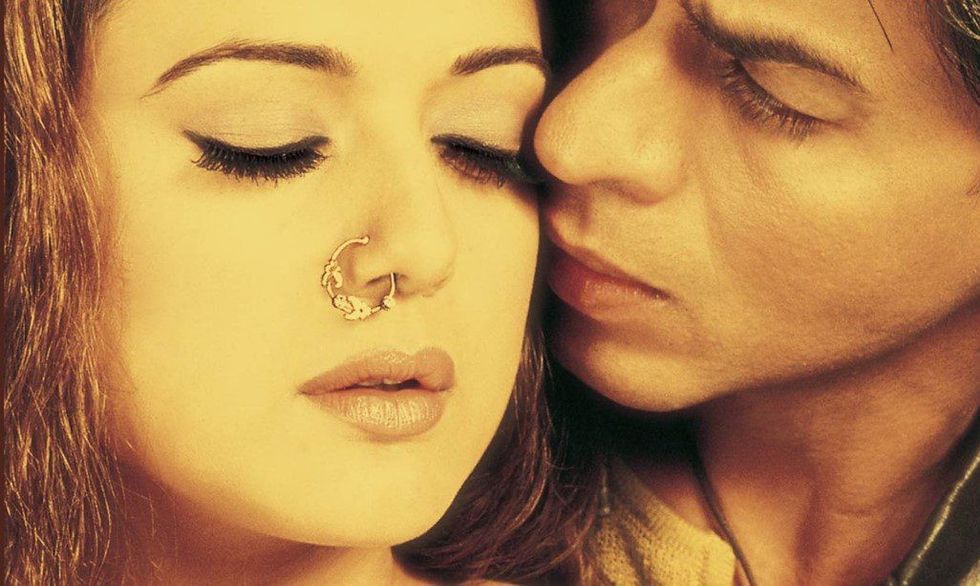

V is for Veer Zaara: Mohan’s unused melodies were recreated by his son Sanjeev Kohli for the Bollywood blockbuster hit Veer Zaara (2004). His favourite singer Lata Mangeshkar sang a majority of the songs, which had new lyrics written by Javed Akhtar. The award-winning soundtrack connected a new generation to the magic of Mohan.

W is for Woh Kaun Thi: For many, the greatest love song in Bollywood history is Lag Jaa Gale from the film Woh Kaun Thi (1964). Interestingly Raj Khosla had initially rejected it but was convinced to change his mind by Mohan and lead star Manoj Kumar. The blockbuster hit remains a classic and has been covered by many singers across the decades, including current Bollywood music queen Shreya Ghoshal.

X is for X Factor: Mohan’s immense ability to add Indian classical music elements gave his songs a more refined and timeless quality, which is why they remain popular today. This enabled the composer to find the middle ground between classical and commercial music, which subsequently connected him to wider audiences. He also took top singers out of their comfort zones.

Y is for Youngster: Mohan was born on June 25, 1924, in Baghdad, where his father worked as an accountant general with the Iraqi police. He spent the first five years of his life living in the Middle East and would spend hours listening to gramophone records as a child, which started his love for music. On his second birthday, he was gifted a small drum and soon developed a natural singing ability. His mother nurtured that love of music further as he grew up.

Z is for Zodiac: The predominant quality Mohan had of his star sign Cancer was being intensely emotional. This sensitive nature affected him deeply, when he faced trauma or didn’t get the recognition he deserved. It also benefitted his songs, which were filled with deep feelings and remain fabulous today.

Jonathan Mayer on the sitar and beyond Instagram/the_sitarist/ @sat_sim

Jonathan Mayer on the sitar and beyond Instagram/the_sitarist/ @sat_sim  Redefining Indian classical music with Jonathan Mayer Akil Wilson

Redefining Indian classical music with Jonathan Mayer Akil Wilson Jonathan Mayer on music without boundaries Instagram/the_sitarist/

Jonathan Mayer on music without boundaries Instagram/the_sitarist/ Jonathan Mayer on teaching and performing Indian music Instagram/

Jonathan Mayer on teaching and performing Indian music Instagram/