BRITISH Asian parents will have to step in and take their children to museums, galleries as well as green spaces and heritage sites – because they can no longer rely on schools to do so.

This is the only conclusion that can be drawn from a speech made last week by Hilary McGrady, director-general of the National Trust.

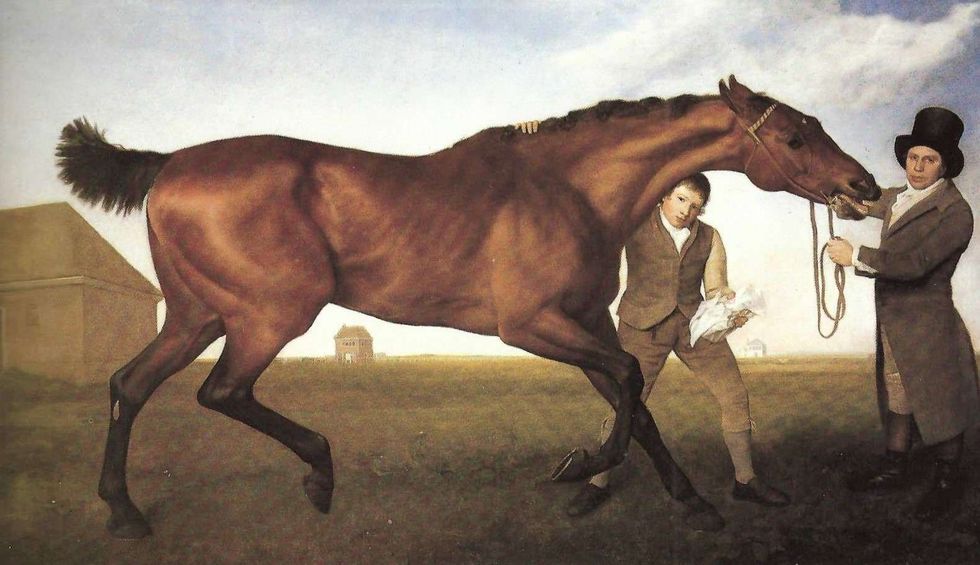

Speaking at the trust’s winter reception at the Young V&A in Bethnal Green, London, she recalled being taken as a 13-year-old on a school trip to see a famous George Stubbs painting at Mount Stewart House, a National Trust property in Northern Ireland.

The monumental 12-ft-wide canvas, showing a horse being rubbed down, was painted in 1800 when Stubbs was 75, just six years before his death, and is considered one of his late masterpieces.

McGrady remembered how her imagination was stirred by the painting: “First of all, I couldn’t figure out how anybody could have as big a house to be able to accommodate a painting of that size. It was genuinely awe inspiring. And, to this day, it is still my favourite painting.”

“But, of course, I was one of the privileged few to have a school visit,” she added. “School visits these days are not that common.”

Earlier in the day, she had visited the V&A in Kensington, where she was heartened to spot “a little crocodile of kids”.

“That’s not that common anymore, and it certainly cannot be taken for granted,” she said. “More and more schools cannot afford those visits anymore, and, more importantly, institutions like ours cannot assume that they (the children) get their entry into our world through a school visit. There are so many barriers that are getting in the way of young people, in particular, engaging with what we are, whether that’s heritage, whether that’s outdoors.”

That does place the onus on British Asian parents to help their children become more familiar with the country’s history and culture through enjoyable visits to museums, galleries and National Trust properties. Nearly a hundred of these sites have strong Indian connections, and seven hosted Diwali celebrations this year.

McGrady pointed out: “We know that 40 per cent of the UK do not have easy access to green quality public space, and that rises to 60 per cent in our inner cities, and that can’t be right. And we know that more and more kids, and particularly young people, young adults, have no access to green space. That’s affecting their mental health and their sense of well-being.

“That is why the trust has been doubling down on how we can engage with this important community of people who need the things that we can offer, but we have to do it on their terms.”

She referred to the trust’s ‘Summer of Play’, a family friendly festival held at its properties. She also praised an initiative by three teenagers in Coventry who were so upset by the illegal felling in 2023 of the Sycamore Gap tree, which had stood beside Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland for over a century, that they started an experiment with saplings.

At Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire, one of the UK’s oldest nature reserves, a rare moth that mimics the appearance of a wasp had become the 10,000th species of wildlife identified on the site.

McGrady said that, at a time when the trust was seeking to cut costs, it had been “brave” in taking on added responsibility for the 10 museums attached to the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire. The Ironbridge Gorge was designated a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1986. The famous Iron Bridge, a Grade I listed structure, will remain under the ownership of Telford and Wrekin Council and is cared for by English Heritage. McGrady showed guests a film made by the trust which revealed how beavers, introduced in 2020 to the Holnicote Estate in Shropshire, had had a beneficial effect. They had slowed down the flow of water in the River Aller, which “massively benefits the local farming community”.

At the Shugborough Estate in Staffordshire, the trust was creating Arcadia, the country’s first forest garden with 80,000 mutually dependent trees, shrubs, herbs, flowers and vegetables.

The film also featured the restoration of Wightwick Manor in Wolverhampton, which is home to an internationally important collection of pre-Raphaelite art and William Morris interiors.

The film concluded: “As William Morris said, we are but trustees of those who come after us. That sense of guardianship has always been at the heart of what we do today as we face the challenges of a changing world.”

René Olivieri, the trust’s chairman, said: “The National Trust is really excited and very proud to be taking these (Ironbridge Gorge) museums and the collections within them into its care, becoming responsible for what is widely seen as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution.”

He went on: “We shouldn’t forget that the National Trust was born out of the Industrial Revolution. Octavia Hill founded it 130 years ago to deal with some of the collateral damage caused by the Industrial Revolution, much of which we’re living with.

“Today, we have a natural world in decline. We have a natural world increasingly removed from people’s daily lives. This year, we’ve revealed our new strategy. In the coming years, the National Trust intends to restore nature, which has been in decline for decades all across the UK, and we’re going to restore it, not just in the places that we look after.

“We’re going to end unequal access to nature, beauty and history. We will become much more active in places where most people live in cities and towns, and we’ll help them discover, restore and find meaning in the heritage and the nature on their doorstep. But most importantly of all, and this really is actually the bedrock of our new strategy, we will work hard to inspire millions more to care for the world around them.

“David Attenborough reminds us all the time, at the end of the day, the health and resilience of our society, our civilisation, depends on the health and resilience of our natural world.”