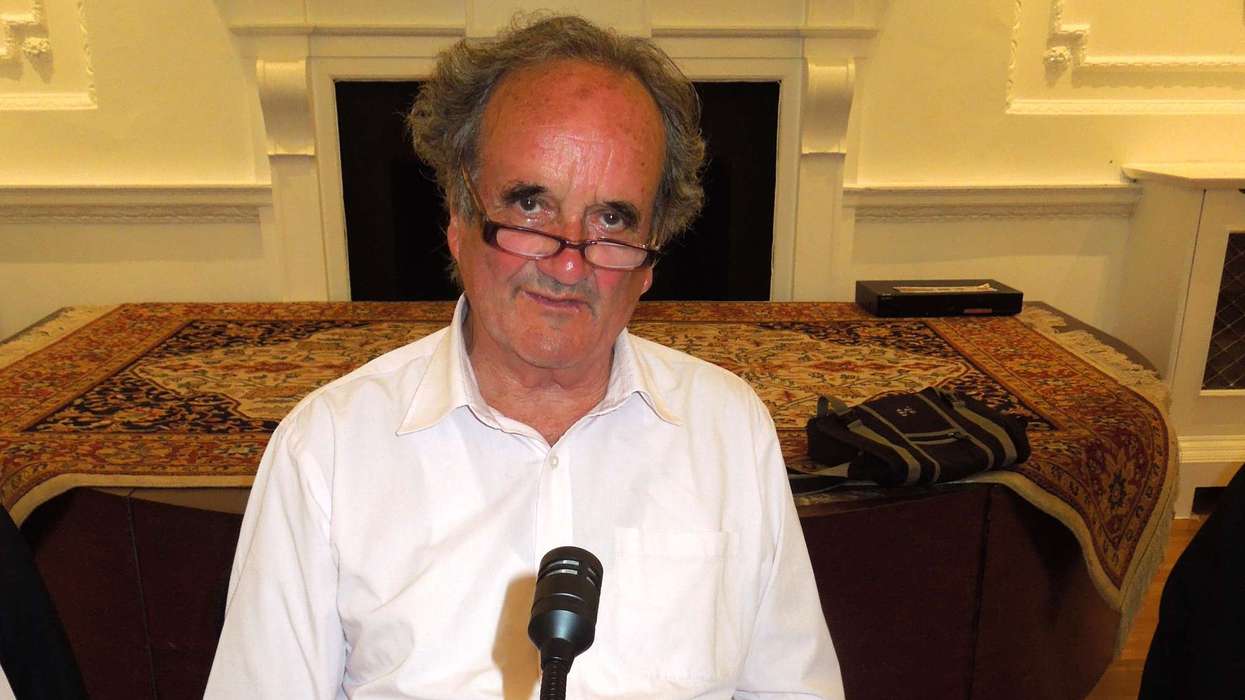

Sir Mark Tully, who has been widely described as “the voice of the BBC in India”, died in Delhi on Sunday, January 25, aged 90.

But what was Mark really like?

One of his books, published in 1988, is called No Full Stops in India.

With his passing, however, the millions who followed Mark’s reporting from India over six decades will have the feeling that something has come to an end. His death does represent some sort of a full stop.

To be sure, he was a pukka Englishman who kept his British passport but he also acquired an OCI (Overseas Citizen of India) card. That made him “a citizen of the two countries I feel I belong to, India and Britain”, he said.

After all, he was born in Tollygunge in south Calcutta (now Kolkata) on 24 October 1935.

I know Tollygunge well as that is where my maternal grandmother lived, along with assorted aunts and uncles.

“Tollygunge was named after me,” Mark once joked.

“I didn’t really say that, did I?” he smiled, when I reminded him of the quip years later.

He was the perfect Englishman who preferred to live in India. The first time, he sent me instructions on how I should get to his flat, which then also served as the BBC office in Delhi.

I took a taxi from my hotel, and guided the driver – “left, right, left….” – from the instructions written down on a bit of paper until we got to his place in Nizamuddin West.

The driver told me I could have saved myself all the trouble: “Saab, why didn’t you just tell me you wanted Tully Saab’s house?”

I think I saw Mark irritated only once. We had gone out for chat in Delhi. He ordered a beer.

Assuming he was just another white foreigner, the waiter brought him a pricey Carlsberg.

Mark sent it back, emphasising he wanted the local brew and scolded the waiter in no uncertain terms: “Tum humko beikoof samja hai (do you think I’m stupid)?”

We also discussed his passion for the old-fashioned Indian steam trains (I much preferred doing Bombay-Calcutta in two hours by Indian Airlines rather than two of three days by train). In fact, he would sometimes ask if he could sit on the footplate of the engine.

“If you are wearing a white kurta pyjama,” I pointed out, “you’d get covered in soot.”

He responded: “I would ask for my money back if I wasn’t.”

We talked about why he became a journalist because after reading history and theology at Trinity Hall, Cambridge (where he was later made an honorary fellow), he had studied theology at Lincoln Theological College with the aim of becoming a priest. He said he realised after two terms he wasn’t cut out to be one.

But religion didn’t entirely leave him. When he presented his weekly programme called Something Understood on Radio 4, he often blended his reflections on Hinduism and Christianity. He would sometimes bring in snatches of qawwali from the Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya Dargah in Nizamuddin West, a renowned Sufi shrine near his home.

Something Understood, which sadly fell victims to budget cuts in 2019, dealt with “topics of religion, spirituality and the larger questions of human life”.

In Christmas 2015, he noted that “many of those who will crowd into churches for Midnight Mass or other services at Christmas will find it difficult to believe the gospel stories literally or to accept the traditional view of Jesus as God come down to earth. But they might well be so moved by the liturgy, the carols, their memories of Christmas past, the sense that this is one day when the world does stop that they wish they could find some meaning in the Christmas story.”

We had a friend in common, Subhash Chakrabarti, a senior journalist on The Times of India, who kept me in touch with what Mark was doing – and vice versa.

Mark’s daughter, Emma Tully, married Peter Kerkar, son of Taj Hotels managing director Ajit Kerkar, in a low-key ceremony held on June 20, 1994 in Bombay (now Mumbai), at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, where he performed the kanyadaan. I attended the reception in London, which I think was held at the Oriental Club in Oxford Street.

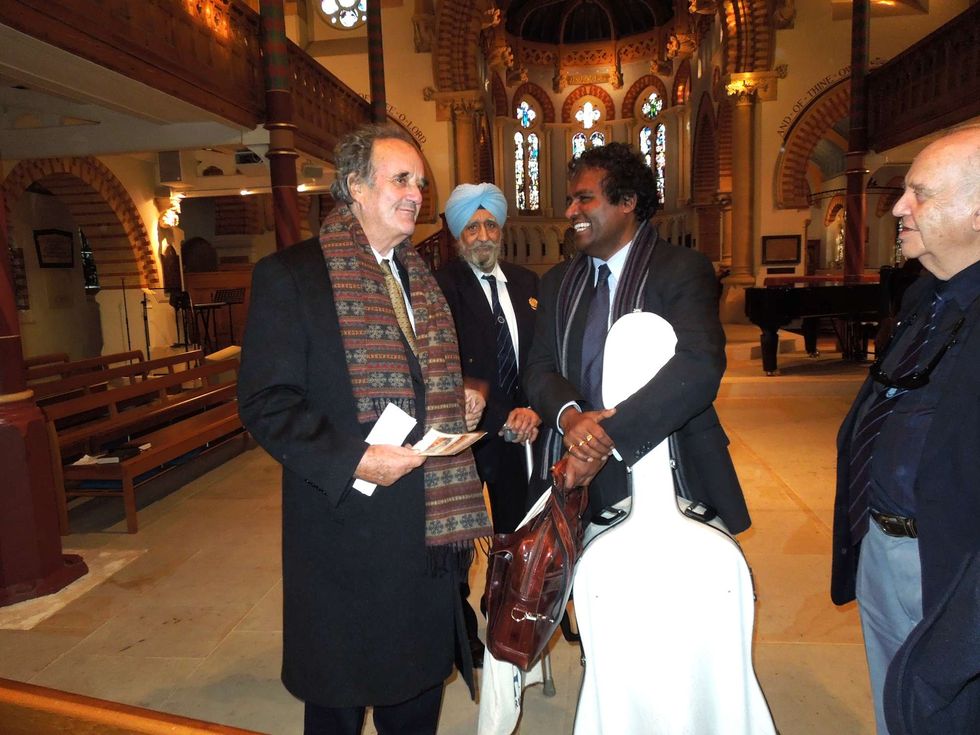

The one occasion I saw Mark being really emotional was when he spoke at the funeral of the actor, Saeed Jaffrey, St Mary’s Church, South Ealing, in 2015 (Saeed, a Shia Muslim, had apparently converted to Christianity).

Mark and Saeed had been friends for 50 years, starting with their early days at the BBC.

“One of the reasons why he was so successful and loved was because of his Shia heritage – being born into a Shia family and very much a man who kept his roots,” remarked Mark, who struggled uncharacteristically to get out his words as several times his voice broke.

He wondered, “Why was he such a loved person?”, and spoke of Saeed’s gentleness, generosity, warmth, sense of fun and remarkable achievements as an actor in both Britain and in Bollywood. “He wanted to build bridges between cultures.”

“My friendship with him started in the heyday, the good old days of the BBC (in the 1960s),” he recalled. “We were a very jolly group – (there were) long evenings together in Bush House Club and I regard that as one of the happiest times of my life and that was when my friendship with Saeed was formed. We must rejoice in the enrichment he brought to our lives.”

As Mark wiped his tears and returned to his seat alongside Jennifer Jaffrey, Saeed’s wife and “rock” for 45 years, the entire congregation broke into spontaneous applause.

“This is the first time I have had applause at a funeral,” remarked Rev Steve Paynter, vicar of the church, who led the “service of thanksgiving and celebration for the life of Saeed Jaffrey, OBE; 8th January 1929-14 November 2015”.

Unusually for a foreign national, Mark was accorded two of India’s top civilian honours: the Padma Shri in 1992 and the Padma Bhushan in 2005. Britain, too, gave him recognition. He was awarded an OBE in 1985, and knighted for services to broadcasting and journalism in the 2002 New Year’s honours list. He described the award as “an honour to India”.

One of Mark’s BBC colleagues, Andrew Whitehead, has summed up: “For decades, the rich, warm tones of Sir Mark were familiar to BBC audiences in Britain and around the world - a much-admired foreign correspondent and respected reporter and commentator on India. He covered war, famine, riots and assassinations, the Bhopal gas tragedy and the Indian army's storming of the Sikh Golden Temple.

“In the small north Indian city of Ayodhya in 1992, he faced a moment of real peril. He witnessed a huge crowd of Hindu hardliners tear down an ancient mosque. Some of the mob – suspicious of the BBC – threatened him, chanting ‘Death to Mark Tully’. He was locked in a room for several hours before a local official and a Hindu priest came to his aid.

“He was a child of the British Raj. His father was a businessman. His mother had been born in Bengal – her family had worked in India as traders and administrators for generations.”

I kept a note of his conversation with Sue Lawley when he was a guest on Desert Island Discs in 2003.

He defended “the good in the Indian caste system”, picked three Indian pieces of music out of the eight allowed, and spoke frankly about how he balanced his personal life between his wife, Margaret, in London, and his partner, Gillian Wright, in Delhi.

Asked by Lawley how he could possibly defend the caste system, Mark said that he was not opposed to change.

“What I have said is we have to look to the good and the bad in the caste system,” Mark argued. “The good side of it is that it offers security, it offers companionship, a community to belong to and that sort of thing.”

When Lawley interjected with, “A community of untouchables?”, an animated Mark responded: “Wait a minute. There were a lot of people who were actually outside the caste system and they were treated as untouchables and that was wholly indefensible. The community is one of the good sides of the caste system and one of the reasons why I wanted to find a balanced view on caste is because so many people dismiss the whole of Indian religion, the whole of India, because of the caste system.”

Tackled on whether western-style economic progress should come to India, Mark said: “I believe very much that India must progress and I would be an absolute idiot if I did not think that the Indian economy should grow. But I don’t believe necessarily that our way (the western way) of doing things is the right way for India. Consumerism is based on greed and who can say that greed is a healthy human emotion? We are the people who have to change because we are the advocates of consumerism and we are also the people who have the economic clout and economic muscle.”

Questioned whether he was at peace living between two women, his wife in London and his partner in India, his reply was candid.

“I am not entirely at peace with it, obviously for obvious reasons of my Christianity but it is something which has happened and there are two wonderful women of whom I am extraordinarily fond,” he replied. “I would not like to say they are totally at peace with it because it is a strange situation but it is not unique. I remember I was friendly with John Betjeman and he was in quite a similar sort of situation.”

Quizzed on whether the arrangement was an attempt to avoid divorce, his answer was: “I don’t think divorce is a healthy or good thing. It is also in part because I wanted to preserve as much as I could of my family life. It is also going back to fate. It is something which has just happened. I do my best to live within it and both Gilly and Margaret do their best to live within it and it’s a situation we find ourselves in.”

Among his eight records were:

Ragini Yamani by Vilayat Khan and Bismillah Khan (“very dear to me; two of the great masters of Indian classical music; I like various forms of Indian music, including Indian classical music”).

Shahbaaz Qalander by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan (“Where I live in India is called Nizamuddin, opposite a Sufi shrine, and Nizamuddin was a great Sufi saint, so I have chosen some quwaali played by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, written in memory of another great Sufi saint, Shahbaaz Qalander”).

Ghanan Ghanani from Lagaan, lyrics by Javed Akhtar, music by A.R. Rahman (“People in India test your Indianness by asking you, ‘Do you like Bombay movies?’ And I like Bombay movies and this is one of the great hits, a very recent one called Lagaan”).

Mark spoke of how his parents, and especially his European nanny, had sought to isolate him from Indian influences when he grew up in Calcutta.

“Nanny’s job was to stop me going native, as you put it,” he told Lawley, adding, “I am not sure I like that phrase.”

When his nanny heard him counting in Hindi, which he had been taught by the family driver, she gave him a clout on the head and scolded him, “That’s the servant’s language, not your language.”

He felt that it was his karma to go on living in India — “one of the reasons why I feel so strongly about India”.

He explained: “India has had a profound effect on the way I live and the whole way I think. It has given me a much greater appreciation of the role of fate in one’s life.”

If Mark was reflecting on his own passing for From Our Own Correspondent, he would probably include the line: “Tully would not have been entirely displeased that he took his last breath in India.”