Hemant Soren, chief minister of the north-east Indian state of Jharkhland, is coming to Britain on a very unusual mission.

He is expected to visit Stonehenge on Saturday, 24 January, in the hope there could be some kind of heritage tie-up with the equally mystical and ancient stone megaliths in his own state.

The megaliths in Jharkhand “are connected with death rituals. Among the Munda and Ho tribes, bones or ashes of the dead are buried after cremation, and a stone memorial is placed there”, according to the state.

“Not all stones mark deaths,” the state goes on. “Some are raised to celebrate births, marriages, or community heroes. The stones act as a record of tribal life remembering both joy and sorrow. Some sites were used for worship or fertility rituals rather than burials. Many are believed to honour a Mother Goddess or ancestors. In some villages, people still pray and apply vermilion on ancient stones, keeping them sacred and safe. These traditions show how megaliths are still part of living tribal faith and culture. In short, Jharkhand’s megaliths are not just ancient stones, they are part of a living tribal culture.”

Soren, who is visiting the UK after first attending the World Economic Forum in Davos, is heading a large delegation that is promoting investment opportunities in Jharkhand.

The state, which is celebrating its 25th anniversary, was created in 2000 by combining 18 districts which were previously part of Bihar. One of Jharkhand’s most famous sons is the former Indian cricket captain, Mahendra Singh Dhoni.

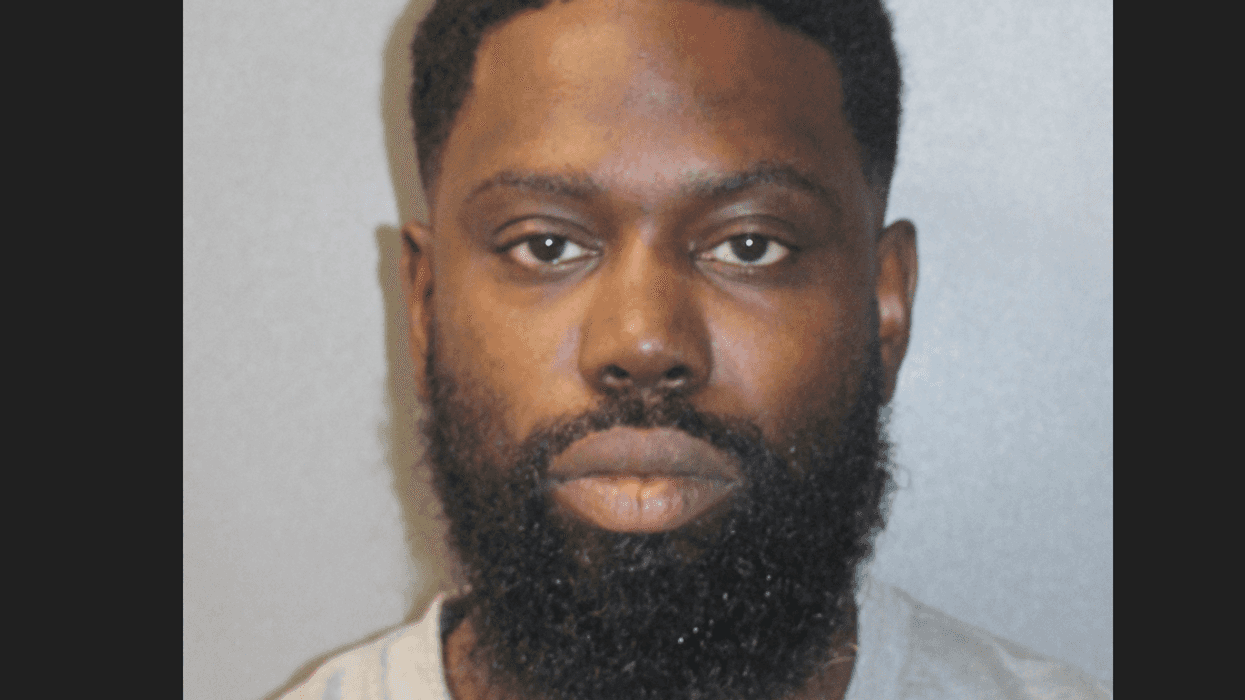

Soren himself is widely admired across India. He was forced to step down as chief minister and jailed for five months on what have been widely regarded as trumped up corruption charges levelled by his political enemies. In the 2024 assembly elections, he swept back to power and became chief minister again last November.

A veteran newspaper editor in India said: “He is a good person. He was jailed but still won the election and returned to power. His former enemies changed tack and are courting him but he has so far resisted.”

Before setting off from the Jharkhand state capital of Ranchi, Soren told Eastern Eye of his Stonehenge mission.

He said: “On the land of Jharkhand, our ancient megaliths and monoliths are not just stone—they are memory, deep history, and the identity of our cultural heritage. Many of these heritage structures remain embedded in villages and forest landscapes, safeguarded by local and Indigenous communities. In the United Kingdom, there is Stonehenge, and our genuine interest lies in collaborating with leading institutions in the UK along with Jharkhand state government on documentation, conservation science, heritage management, and community custodianship.”

He added: “We will work towards global recognition, including a credible pathway for UNESCO consideration, and we will strengthen protection through dedicated policy instruments—so that these heritage landscapes receive the care, respect, and global visibility they deserve.”

Stonehenge, one of Britain’s most popular destinations – adults tickets cost between £25 and £31.50 – attracted over 1.3m visitors in 2026.

Stonehenge, on the Salisbury Plan in Wiltshire, is owned by the Crown Estate and managed by English Heritage; the surrounding land is owned by the National Trust.

History books say that “Stonehenge was constructed in several phases beginning about 3100 BC and continuing until about 1600 BC”. Among other uses, it served as “a prehistoric temple for sun worship, a large cemetery for cremated remains, a calendar to track seasons and astronomical events like solstices, a site for ceremonies and feasts, and possibly a healing centre”.

An English Heritage spokesperson said: "Caring for one of the world's most famous places and a UNESCO World Heritage site is an enormous privilege and responsibility. Stonehenge is a powerful testament to human ingenuity, imagination and creativity and we are continuously learning and discovering more about its creation and the communities who built and visited the site.

"It is our charitable mission to share this unique site with people from all over the world, and we currently welcome around 1.4million visitors annually. We also provide free visits for schools and work is currently underway to build an authentic Neolithic Hall to host education visits. We hope this will be an incredible educational experience for students and instil a lifelong love of learning in every single child."Soren is looking to learn lessons from Stonehenge and apply them to the megaliths in Jharkhand.

He is considering building protective walls to stop encroachment, add a visitor centre, try and win international heritage status, and hold music, dance and craft festivals to mark the equinox sunrise and solstice events in order to attract tourists in the manner of Stonehenge.

An official statement from Jharkhand prior to the chief minister’s departure said that the megaliths formations in the state “invite comparison with iconic sites such as Stonehenge in the United Kingdom, reflecting a shared human impulse across continents and millennia to anchor time, death, and cosmic order in stone”.

It said: “By presenting this heritage alongside its economic and development vision at Davos and in the United Kingdom, Jharkhand is offering a perspective that is increasingly vital to the global conversation: that long-term growth must be anchored in ecological memory, cultural continuity, and respect for deep time.”

It pointed out: “This narrative also aligns closely with the India–United Kingdom cultural preservation and cooperation framework, which promotes ethical conservation, museum partnerships, research exchange, and the protection of heritage in Situ. Jharkhand’s megalithic landscapes, preserved not in distant collections but in living villages and forests, represent a powerful example of how heritage can be safeguarded while remaining embedded within its communities.”

The statement said: “As Jharkhand prepares to engage with global leaders at the World Economic Forum annual meeting 2026 in Davos and during its official visit to the United Kingdom, the state is also bringing to the international stage a deeper story of land, time, and cultural continuity, one rooted in one of the oldest living stone traditions on earth.”

It pointed out: “Jharkhand lies on the Singhbhum Craton, one of earth’s earliest stable landmasses, formed over 3.3 billion years ago. Once submerged beneath primordial oceans, this ancient crust slowly rose above the waters through immense geological forces, becoming one of the planet’s first enduring continental surfaces. From this emergence came the soils, forests, and mineral wealth that would later sustain both ecosystems and human civilisation.

“Across this ancient geological foundation, human communities have, for millennia, raised megaliths, monoliths, and stone circles to mark memory, ancestry, and cosmic order. Unlike most megalithic cultures across the world, which survive only as archaeological remains, Jharkhand’s stone traditions remain active and living, maintained by indigenous communities who continue to use these sites for ritual and remembrance.

“Sites such as Chokahatu in Ranchi district, the largest living megalithic landscape in the Indian subcontinent, continue to receive new memorial stones placed by the Munda community, creating a layered archive of lineage and memory that spans across centuries.

“At Punkri Barwadih in Hazaribagh, carefully aligned monoliths track the movement of the sun across the year, placing Jharkhand within the global history of prehistoric astronomy.

“Together with sacred cave complexes such as Isko and the fossilised forests of Mandro, these landscapes form a rare continuum where deep planetary time and living human culture coexist in the same geography.”

Soren is expected to meet Seema Malhotra, who looks after India in her capacity as parliamentary under-secretary of state in the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office.

The chief minister has also asked for a meeting with the culture secretary Lisa Nandy, who signed a UK-India cultural agreement when she visited India last year. His delegation is meeting British experts to discuss critical minerals and mines, and also visiting the British Museum.

Soren is also going to Oxford, where he will pay tribute to Jaipal Singh Munda, who was the first tribal to study at the university.

Munda became something of a legend. He was at St John’s College from 1924 to 1926, won a hockey Blue (by playing against Cambridge) and captained the Indian team to its first Olympic hockey gold in Amsterdam in 1928. He died, aged 67, in 1970 but is hero worshipped as “Marang Gomke” (meaning Great Leader in Santali) after campaigning for a separate homeland for the Adivasi tribes in central India.