MEDICAL exams remain unfair and continue to disadvantage non-white doctors despite claims of progress, a leading Asian physician has cautioned.

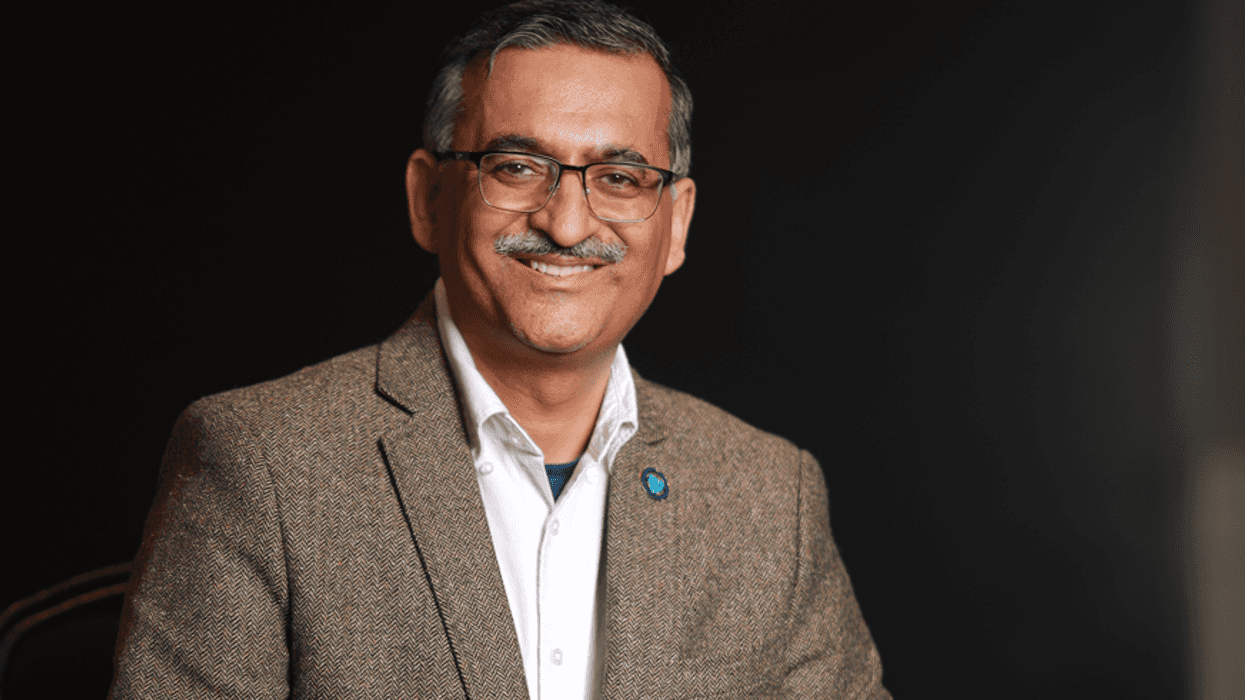

Dr Joydeep Grover, president of the British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (BAPIO) Foundation, said exam outcomes remain “deeply flawed” with “almost negligible” progress made in tackling disparities between white and non-white candidates.

His comments came as a new General Medical Council equality, diversity and inclusion report, published last Thursday (15), found that deep-rooted inequality continued to limit opportunities for ethnic minority and non-UK trained doctors in the NHS, weakening workplace culture and potentially harming long-term patient care.

Grover told Eastern Eye last week, “BAPIO has been working very hard with the GMC to take action on employer referrals. We are pleased that the numbers are reducing because of the actions we proposed and which the GMC has acted upon.

“It has been an uphill journey, but improvements are being noted, and we hope this trend will continue. That is one part of the issue, and overall that is a reasonably positive position.”

He added, “The other problem, which remains a very significant issue, is exam outcomes. These are deeply flawed, and there has been no real progress on this. The GMC said there has been a seven per cent improvement, but that is largely because the pass marks have been lowered. “However, there remains a clear problem in the outcomes for UK graduates who are white compared with those who are not white. Progress on this has been almost negligible.”

Grover said the exams put at a disadvantage both international medical graduates and UK graduates from ethnic minority backgrounds, and pointed to a “cultural element” in how they are structured.

“In radiology, which is an exam based much less on verbal communication, international medical graduates tend to perform better,” he explained. “In exams that involve a lot of speaking, international medical graduates perform much worse. This is also true for UK graduates who are not white.” He said it was a structural problem, and wondered whether exams tested knowledge and its application or “nuances of language”.

The GMC report published last Thursday showed progress in some areas.

The proportion of employers with excess referrals linked to ethnicity or place of qualification fell by 48 per cent, from 5.6 per cent to 2.9 per cent, compared to figures from 2016 to 2020.

The regulator said it was on track to meet its target of eliminating disproportionate employer referrals by the end of this year. BAPIO welcomed this development, having worked with the GMC for years to address the issue.

However, the report also revealed challenges. Ethnic minority staff were more likely to leave the organisation, with turnover rates nearly five percentage points higher than other employees. The GMC has set a longer-term goal of eliminating discrimination and unfair outcomes in education by 2031, but the latest findings show limited improvement for ethnic minority doctors who trained in the UK and for medical students.

GMC chief executive Charlie Massey said inequality in medicine is “not inevitable” and urged healthcare leaders and employers to take stronger action.

“Fairness and equality aren’t simply matters of principle – they are prerequisites for productivity and translate to better patient care,” Massey said. “Every doctor, no matter their background, must be able to work, learn and thrive in an environment where they feel they belong.”

Massey acknowledged the uneven progress: “Our report shows we have a system moving at two speeds. There is unmistakable momentum towards eradicating disproportionality in employer referrals, but limited, and in some measures absent, progress in education, which must be addressed.”

Grover criticised the fragmented approach to addressing inequality, noting that while the Royal College of Psychiatrists has taken steps to reduce differential attainment (the gap between attainment levels of different groups of doctors) with some success, many other colleges continued to assume international graduates simply lack communication skills.

“In some colleges, differential attainment is almost accepted as inevitable, and there is little appetite to address it,” he said.

BAPIO published a report on differential attainment, “Bridging the Gap”, in 2021 through its Institute of Health Research, which Grover said should be read by everyone involved in medical education.

He said, “The first step is to acknowledge there is a problem. The second is to accept what has been done so far has not worked. Leaders must be willing to say, ‘We got this wrong,’ and then undertake a comprehensive review of why it went wrong. To some extent, with employer referrals to the GMC, there was acknowledgement of the problem, and that allowed action to be taken.”

He also warned that proposed legislation prioritising UK graduates could trigger a “mass exodus of international doctors and severe shortages in the NHS in the very near future”, compounding existing problems caused by poor workforce planning. “Over the past two years, too many doctors arrived in the UK without sufficient job opportunities, and many have been unable to find posts,” Grover said, adding that many international doctors are already returning to India or choosing other destinations.

In its report, the GMC called on governments, NHS bodies and health leaders across the UK to treat equality and inclusion as central to workforce planning and patient safety.

Among its recommendations, the regulator called for mandatory induction programmes for international medical graduates, better monitoring of disciplinary actions, stronger anti-racism resources, and closer collaboration across the health system.

Massey said disadvantages early in a doctor’s career can have lasting effects.

“If doctors face disadvantage early in their careers, or before they begin them, they are already on an unequal footing,” he said. “Inequalities are not inevitable, but they can reverberate throughout a lifetime.

“Entrenched disadvantage will have far-reaching consequences for doctors, services and patients. We must all play our part to tackle this challenge head-on.”

NHS Providers chief executive Daniel Elkeles said, “These findings underline the fact that there is still a lot for the NHS to do to tackle discrimination and inequality in medicine. It is encouraging to see the gap in fitness to practice referrals is narrowing. We must build on this.

“The lack of progress in medical education and training is a real concern for doctors, patients and for the NHS. Trusts are committed to tackling these inequalities. While we strongly support the government’s moves to prioritise UK-trained doctors for training posts, it is very important that the contribution made by internationally educated staff in the NHS is respected and valued.”