PAKISTAN has become the latest Asian country to introduce enhanced screening measures for the deadly Nipah virus, joining at least six other nations implementing border controls despite assurances from Indian and WHO officials that the risk of spread remains low.

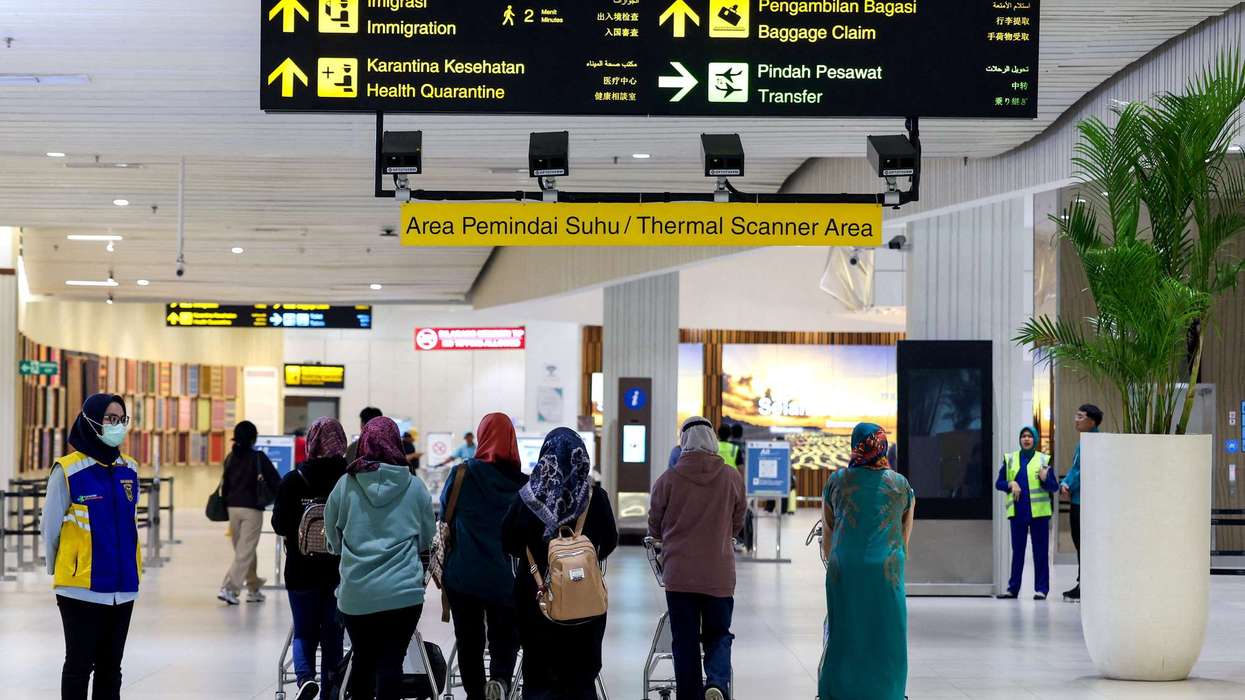

Pakistan's Border Health Services department announced on Thursday (29) that authorities had ordered strengthened surveillance measures at all points of entry, including seaports, land borders and airports, following India's confirmation of two Nipah infections in late December.

"It has become imperative to strengthen preventative and surveillance measures at Pakistan's borders," the department said in a statement, adding that "all travellers shall undergo thermal screening and clinical assessment at the Point of Entry."

The agency said travellers would need to provide transit history for the preceding 21-day period to check whether they had been through "Nipah-affected or high-risk regions."

Nipah is a rare viral infection that spreads largely from infected animals, mainly fruit bats, to humans. While it can be asymptomatic, it is often very dangerous, with a case fatality rate of 40 per cent to 75 per cent, depending on the local healthcare system's capacity for detection and management, according to the WHO.

The virus can cause fever and brain inflammation, and there is currently no vaccine or cure, though vaccines in development are still being tested. Person-to-person transmission is not easy and typically requires prolonged contact with an infected individual.

Thailand, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam have similarly tightened screening at airports in recent days, though there are no direct flights between Pakistan and India and travel between the neighbouring countries remains extremely limited, particularly since their worst fighting in decades erupted last May.

Indian health authorities have sought to downplay concerns, insisting there is no outbreak and no need for airport screening within the country. Officials said this week that authorities have identified and traced 196 contacts linked to the two cases, with none showing symptoms and all testing negative for the virus.

"There is no outbreak, there were just two cases in one district in (West) Bengal and there is no spread," a federal health ministry official told Reuters, speaking on condition of anonymity. "There is no consideration for screening at airports in India because there appears to be no need for it."

Asked about Indian passengers being screened at airports across Asia, the official said it was the sovereign right of countries to do what they think is best.

The two infected individuals are healthcare workers in West Bengal. The chief district medical officer in the eastern state told Reuters on Thursday that the male patient was doing well and likely to be discharged from hospital soon, while the female patient remain critical and under treatment.

The WHO backed India's assessment on Friday (30), saying the risk of spread was low on national, regional and global levels.

"The WHO considers the risk of further spread of infection from these two cases is low," the agency told Reuters in an email, adding that India had the capacity to contain such outbreaks and that "there is no evidence yet of increased human to human transmission."

Anaïs Legand, an official with WHO's Health Emergencies Programme, told a Geneva press briefing that neither infected person had travelled while symptomatic, and both patients remained alive and hospitalised, with one showing signs of improvement.

"The risk on a national, regional and global level is considered low," Legand said, though she noted the WHO was waiting for India to release the viral sequence to assess any possible mutation. However, she added there was "no specific evidence that would make us worry for the time being."

The WHO said it did not recommend travel or trade restrictions, though it did not rule out further exposure to the virus, which circulates in bat populations in parts of India and neighbouring Bangladesh.

The source of the current infections remains unclear. "Hypotheses such as infection from drinking palm juice or exposure at healthcare facilities are being considered," Legand said.

The global health body classifies Nipah as a priority pathogen because of the lack of licensed vaccines or treatments, its high fatality rate, and fears it could mutate into a more transmissible variant.

India regularly reports sporadic Nipah infections, particularly in the southern state of Kerala, regarded as one of the world's highest-risk regions for the virus and linked to dozens of deaths since it first emerged there in 2018. The current outbreak is the seventh documented in India and the third in West Bengal.

As of December 2025, there have been 750 confirmed Nipah infections globally, with 415 deaths, according to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, which is funding a vaccine trial.

(Reuters)