PAKISTANI rescuers pulled seven children and one man to safety after their cable car became stranded high over a remote ravine on Tuesday (22), ending an ordeal lasting more than 15 hours.

"It was a unique operation that required lots of skill," the military said in a statement.

The high-risk operation in the north of Pakistan was completed in the darkness of night after the cable car snagged early in the morning, leaving it hanging precariously at an angle all day.

"All the kids have been successfully and safely rescued," caretaker prime minister Anwaar-ul-Haq Kakar said in a post on Twitter.

"Great team work by the military, rescue departments, district administration as well as the local people."

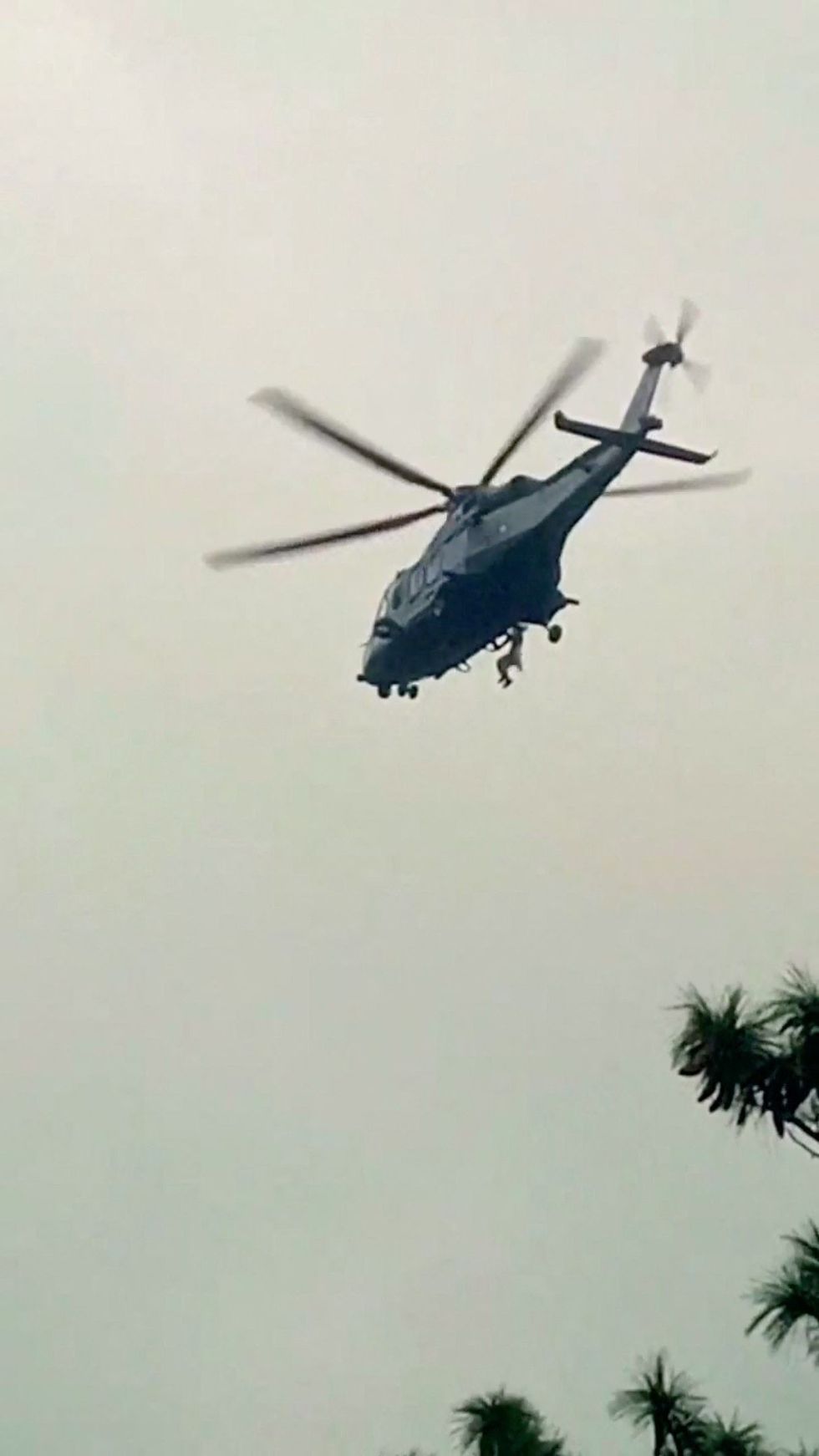

A military helicopter rescue operation was called off as night fell after two children had been pulled to safety. Flood lights were installed and a ground-based rescue continued.

A security source said cable crossing experts had been trying to rescue the children one by one by transferring them on to a small platform along the cable.

Before the helicopter rescue was called off, TV footage showed one child being lifted off the cable car in a harness, swinging side to side, before being lowered to the ground.

The rescue effort transfixed the country, with Pakistanis crowded around television sets, as media showed footage of an emergency worker dangling from a helicopter cable close to the small cabin, with those onboard cramped together.

"An extremely difficult and complicated operation has been successfully completed by the Pakistan military," the military said in a statement.

"All stranded persons were safely evacuated and moved to a safe place... Civil administration and locals also actively came forward to participate in this operation."

A video shared by a rescue agency official showed more than a dozen rescuers and locals lined up near the edge of the dark ravine, pulling on a cable until a boy attached to it by a harness reached the hillside safely to cries of "God is great".

"It is a slow and risky operation. One person needs to tie himself with a rope and he will go in a small chairlift and rescue them one by one," said Abdul Nasir Khan, a resident.

One of the cable lines carrying the car snapped at around 7 am (0200 GMT) as the students were travelling to school in a mountainous area in Battagram, about 200 km (125 miles) north of Islamabad, officials said.

The cable car got stuck half way across the ravine, about 275 metres (900 feet) above ground, Shariq Riaz Khattak a rescue official at the site, told Reuters.

The helicopter rescue mission had been complicated by gusty winds in the area and the fact that the helicopters' rotor blades risked further destabilising the lift, he said.

"Our situation is precarious, for god's sake do something," Gulfaraz, a 20-year-old on the cable car, told local television channel Geo News over the phone. He said the children were aged between 10 and 15 and one had fainted due to heat and fear.

"Once everyone had been rescued, the families started crying with joy and hugging each other," emergency official Waqar Ahmad said over the phone.

"People had been constantly praying because there was a fear that the rope might break. People kept praying until the last person was rescued."

Syed Hammad Haider, a senior Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provincial official, said the gondola was hanging about 1,000 to 1,200 feet above the ground.

Cable cars that carry passengers - and sometimes even cars - are common across the northern areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and Gilgit-Baltistan, and are vital in connecting villages and towns in areas where roads cannot be built.

(Agencies)