TOM STOPPARD, one of Britain’s foremost playwrights, died on November 29 last year, aged 86, so his play, Indian Ink, currently being staged at Hampstead Theatre in north London, is by way of a tribute to him.

It is certainly a play on British Indian relations that Eastern Eye readers should try and see. It has a story within a story within a story.

The play centres on a young English poet, Flora Crewe, who arrives in India in April 1930 in the princely state of Jummapur and forms a relationship with a local artist, Nirad Das, who paints two portraits of her.

Flora decided to travel to India because her doctor has advised her to find somewhere warm to help her with her damaged lungs. The story of the poet and the artist is recalled by Flora’s younger sister, Mrs Eleanor Swan, but from the perspective of England in 1983.

It is not entirely clear whether Flora and Nirad actually had a romantic affair. But what is woven into Indian Ink is the complexity of the relationship between Britain, once the colonial power in the days of the Raj, and India.

Though a twist of history, Stoppard spent his boyhood days in Darjeeling in the Indian Himalayas. It was a period he later described as a “lost domain of uninterrupted happiness”. How he got to India can itself be the subject of a thriller with many twists and turns.

Tom Stoppard was born Tomáš Sträussler on July 3, 1937, into a Jewish family in Zlín, Czechoslovakia.

His father, Eugen Sträussler, a doctor who worked for the Bata shoe company, was evacuated with his wife, Martha Becková, and their two sons, to a branch of the firm in Singapore in March 1939, when the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia. They became refugees a second time in 1941, when the Japanese attacked Singapore.

With his mother and his elder brother, Tomáš, found their ship docked in Bombay (now Mumbai) instead of Australia. They ended up in Darjeeling via Cawnpore (Kanpur), Lahore, Calcutta (Kolkata), and Bhattanagar. Tomáš attended Mount Hermon School, an American Methodist-run institution where he learned English. By and by, he and his brother became “Tom” and “Peter”. Their father did not make to India.

It is believed his ship was sunk by the Japanese in 1942. In 1945, Martha married Kenneth Stoppard, an English major in the British army. Tomáš/ Tom grew up in India from 1941-1946, between the ages of four and eight, in Darjeeling. In 1946, the whole family moved to Nottingham. This was the start of Tom Stoppard’s journey towards becoming a full-fledged “honorary Englishman”. But something of his Indian childhood remained deep in his consciousness.

In 1991, he wrote a radio play, In the Native State, which he adapted for the stage as Indian Ink in 1995.

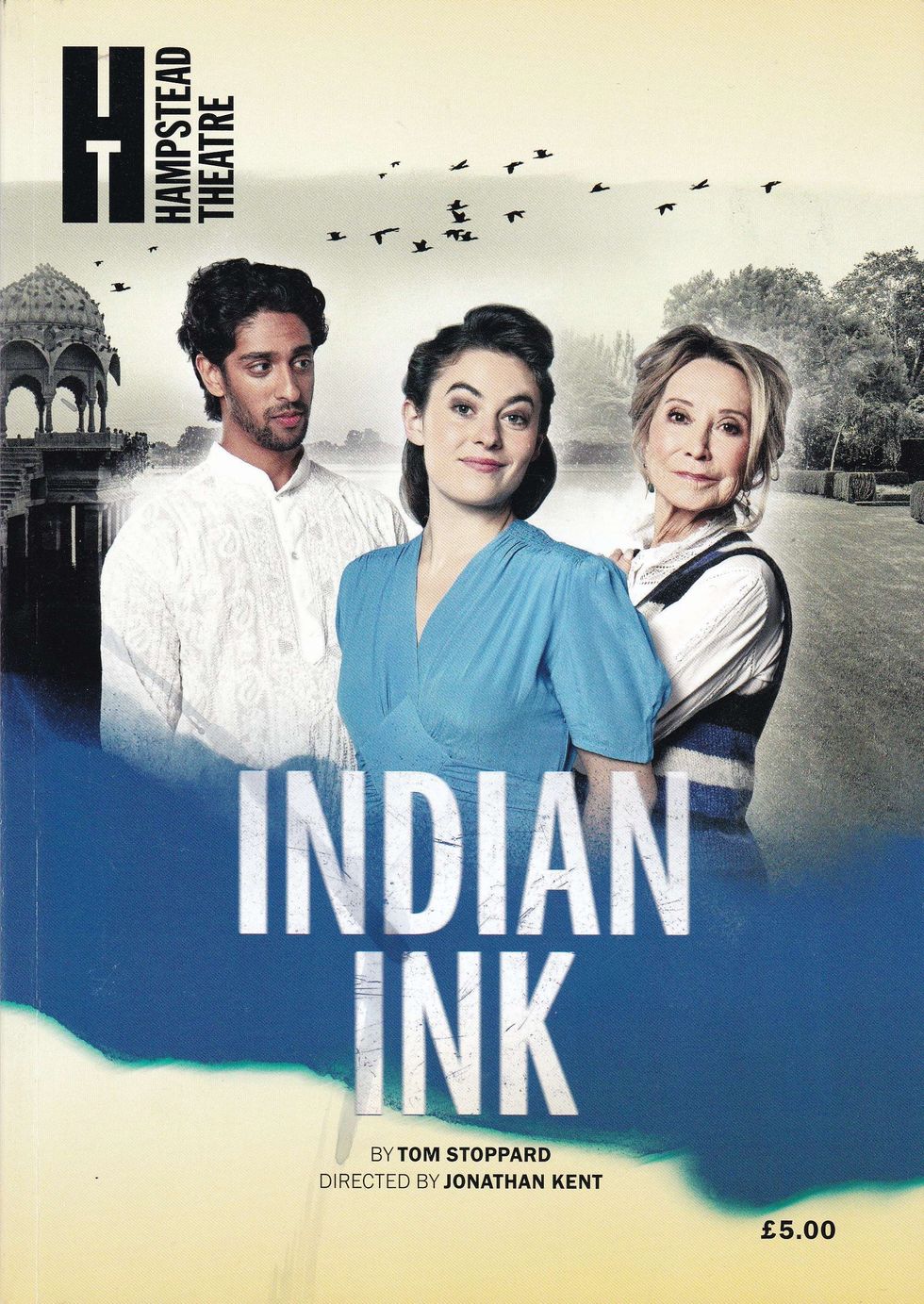

I remember seeing it when it premiered at the Aldwych Theatre, with Felicity Kendal, then 49, cast as Flora Crewe. At Hampstead Theatre, aged 79, she has taken on the role of Flora’s younger sister, Mrs Eleanor Swan (sometimes called Nell in her youth), recalling the past as a 74-year-old woman in 1983.

In 1995, Nirad Das was played by Art Malik. At Hampstead Theatre, the role has gone to Gavi Singh Chera, with Ruby Ashbourne Serkis as Flora.

Back in the 1990s, Stoppard had written the play with Felicity in mind. Her connections with India are even deeper. She and her elder sister, Jennifer, spent their youth in India, where their parents, Geoffrey and Laura Kendal, toured the country in the 1940s-1950s with their Shakespearean theatre troupe, Shakespeareana. Their adventures inspired the Merchant Ivory film, Shakespeare Wallah.

Jennifer married the actor, Shashi Kapoor, and they are survived by their two sons, Kunal and Karan (a London-based photographer, he attended first night of Indian Ink at Hampstead Theatre) and a daughter, Sanjana (who previously ran the Prithvi Theatre in Mumbai).

Indian Ink has as distinguished a cast, as it did in 1995. Directed by Jonathan Kent, the cast this time includes Sagar Arya as Coomaraswami, the president of the Theosophical Society who receives Flora when she first arrives at the train station in Jummapur; Aaron Gill as Anish Das, Nirad’s artist son from his father’s second marriage; Irvine Iqbal as the Rajah of Jummapur who also plays a politician in independent India; Sushant Shekhar as Nazrul, the servant who looks after Flora; and Neil D’Souza as Dilip, a witty guide and scholar.

Stoppard tries to capture the sights and smells and atmosphere of 1930s India, when some of the Brits had cordial relations with senior Indians, but the latter were still excluded from British clubs. Tom Durant-Pritchard fits the bill as the dashing army officer, David Durance, junior political agent to The Resident (Mark Carlisle). Eldon Pike (Donald Sage Macakay) is the eager American editor seeking intimate biographical material for his book on Flora.

Stoppard returned to India for the first time in 1991 and went up to Darjeeling to try and find traces of his childhood. There weren’t many. He noted the town “used to smell of ponies and now it smelled of Land Rovers”. He was treated as a literary grandee when he attended the Jaipur Literary Festival in 2012 and 2018.

The same stage is cleverly used for time past and present. Flora writes poems and letters (to her sister) and Nirad paints her portrait on the right hand side of the stage. The time is 1930. On the left is England in 1983, with Eleanor Swan discussing her younger sister, Flora, with Pike and Nirad’s son, Anish.

What is important is Stoppard’s belief that cultural and racial differences can be dissolved by a love of art, as probably happened between Flora and Nirad.

The programme includes an essay, “Victorian academic art and Indian taste in the colonial era”, by art historian Prof Partha Mitter, who notes that in 1854 the East India Company embarked on a project to “improve” Indian taste as part of its moral upliftment.

Flora, however, wants Nirad to be more authentically Indian and prefers the miniature he has done of her, rather than the more conventional portrait. In the miniature, he depicts her as Radha, “the most beautiful of the herdswomen, undressed for love in an empty house”.

Flora writes to her sister that “perhaps my soul will stay behind as a smudge of paint on paper”. Perhaps Nirad had known all along that Flora was dying, it is suggested. Indian Ink ends with Nell (Eleanor Swan when young) bending over her sister’s grave in India and reading the inscription: “Florence Edith Crewe … Born March twenty-first 1895…Died June tenth 1930. Requiescat In Pace.”

She resolves to add the word “Poet” to the headstone.

In the play, Flora is moved when Nirad shows her the Rajput miniature for the first time by moonlight: “Oh…. it’s the most beautiful thing…”

Flora, who has learnt about the nine rasas from Nirad, enthuses: “It has rasa.”

Nirad identifies the rasa as Shringara.

She responds: “Yes. Shringara. The Rasa of erotic love. Whose god is Vishnu.”

She goes on: “Whose colour was black.”

Das says: “Shyama. Yes.”

Flora wonders: “It seemed a strange colour for love.”

Das tells her: “Krishna was often painted shyama.”

Flora understands: “Yes, I can see that now. It’s the colour he looked in the moonlight.”

n Indian Ink is at Hampstead Theatre until February 7