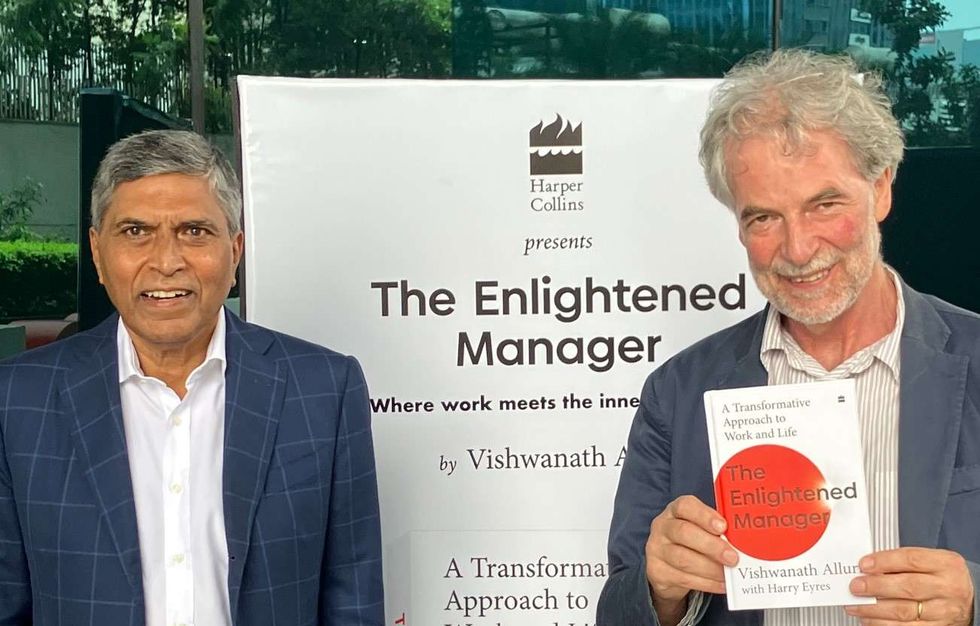

Vishwanath Alluri, a former Indian tech entrepreneur, and Harry Eyres, an eminent English journalist, have written an unusual book on management that has been inspired by the teachings of one of the greatest sages of modern times, Jiddu Krishnamurti.

Their book is called The Enlightened Manager: A Transformative Approach to Work and Life. It is meant to be a business book unlike any other.

“Basically, my book is a gateway to Krishnamurti,” Alluri told Eastern Eye.

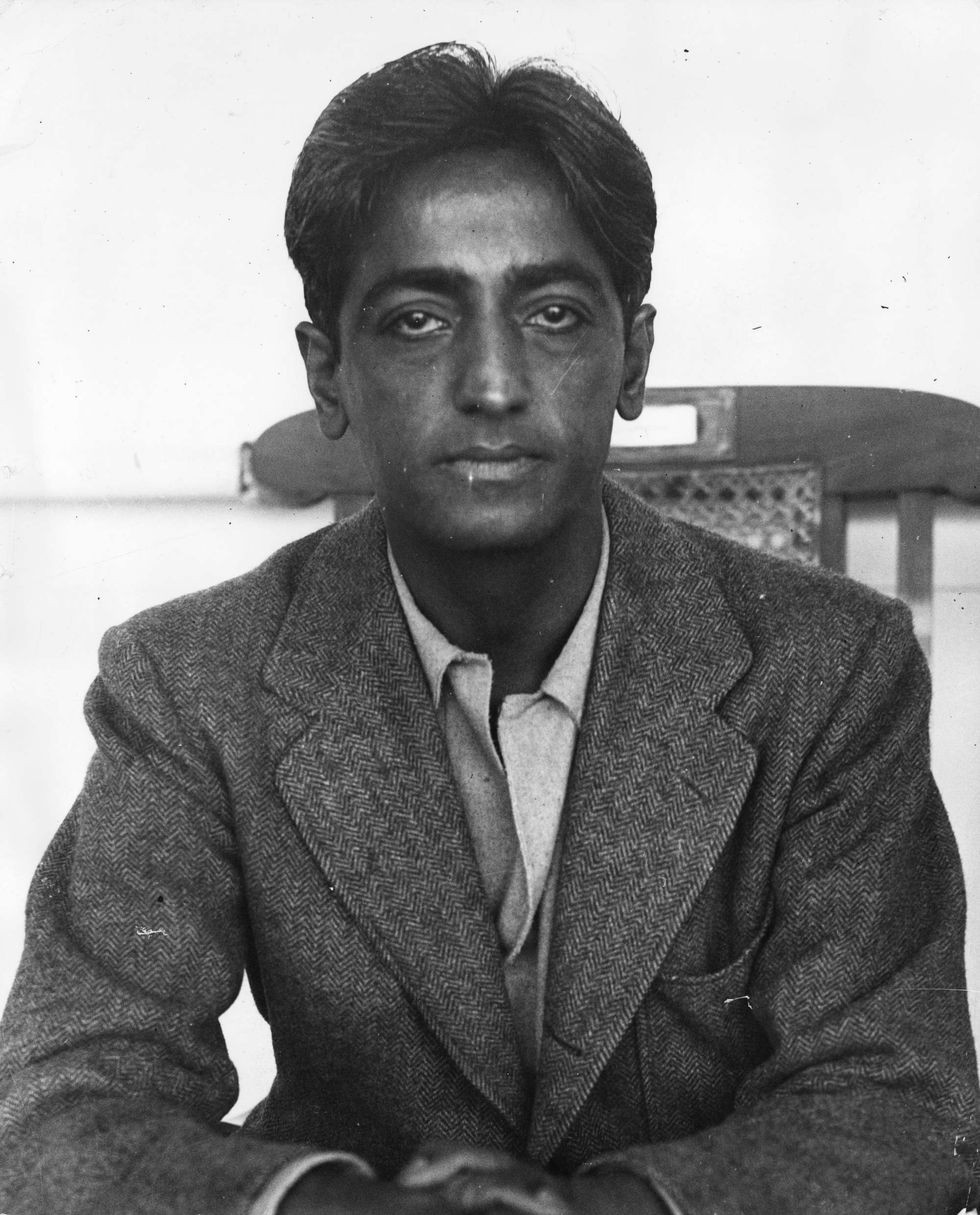

Krishnamurti, sometimes called “K” by his followers across the world, was born on 11 May 1985 and died on 17 February 1986. He has been hailed as “an Indian spiritual figure, speaker, and writer. Adopted by members of the Theosophical Society as a child, Krishnamurti was raised to fill the mantle of the prophesied ‘World Teacher’, a role tasked with aiding humankind’s spiritual evolution.”

For more than 50 years, Krishnamurti travelled annually to the US – he lived for several months of the year in Ohio – before addressing audiences in the UK and Switzerland.

In India, the Krishnamurti Foundation Trust, of which Alluri is the secretary, runs six schools. One was founded in 1934 in Varanasi. There is now also a Krishnamurti artisan school near Pune, where young people are encouraged to work with skilled craftsmen.

According to the trust, “J Krishnamurti is widely regarded as one of the greatest philosophers and teachers of all time. For seven decades, he spoke around the world to large audiences and with numerous individuals, including writers, scientists, philosophers and educators.”

It adds that “Krishnamurti was concerned with all humanity, held no nationality or belief, and belonged to no group or culture. He founded schools in India, the UK and the USA which continue to educate for the total understanding of humanity and the art of living. Krishnamurti stressed that only with this profound understanding can we live in peace: ‘There is hope in humanity, not in society, not in systems, not in organised religious systems, but in you and in me.’ ”

Alluri was once a successful IT man. He founded the technology company IMISoft in 1988 with “a mission to harness India’s intellectual resources and bring them to the world stage”. In 1999 he founded the communication platform IMImobile. His engineering venture was acquired by Ramboll, a Danish engineering conglomerate in 2011, and IMImobile was acquired by CISCO in 2021. But he has given up the world of business to devote himself full time to the work of the foundation. There was a time when he travelled frequently to London, where his companies were based.

Harry Eyres, who was a King’s Scholar at Eton College and read English language and literature at Trinity College, Cambridge, is best known for the column “Slow Lane” in the Financial Times weekend edition, which he created and wrote weekly from 2004 to 2015. This “focused on the creative use of leisure time”. He was also a theatre critic and arts writer for The Times from 1987 to 1993, the wine editor of Harpers & Queen from 1989 to 1996, and the wine columnist for The Spectator magazine from 1984 to 1989. He was poetry editor of The Daily Express from 1996 to 2001.

Krishnamurti, for whom education was always a primary concern, felt that if only the young and the old could be awakened to their conditioning of race, nationality, religion, tradition and opinion – which inevitably leads to conflict – they might bring a totally different quality to their lives.

Maybe he anticipated the age of Donald Trump for he once said: “Education should help us to discover lasting values so that we do not merely cling to formulas or repeat slogans; it should help us to break our national and social barriers, instead of emphasising them, for they breed antagonism between man and man. Unfortunately, the present system of education is making us subservient, mechanical and deeply thoughtless; though it awakens us intellectually, inwardly it leaves us incomplete, stultified and uncreative.

“Without an integrated understanding of life, our individual and collective problems will only deepen and extend. The purpose of education is not to produce mere scholars, technicians and job hunters, but integrated men and women who are free of fear; for only between such human beings can there be enduring peace.”

Alluri “discovered” Krishnamurti some 30 years ago by coming across a video of one of the sage’s conversations. This happened at the Rishi Valley School in Andhra Pradesh, one of the six schools in India run by the trust.

“I switched on the video and it was like a bolt from the blue,” recalled Alluri. “It had an intriguing title – ‘where knowledge and silence go together’. I come from the same neighbouring district in south India as Krishnamurti. I had heard his name but did not know what he was all about. Watching the video was a moment in one’s life when lightning strikes and there is brightness from the dark clouds.”

He explained that Krishnamurti should not be seen like a guru or a philosopher in the conventional sense. “He didn’t wear any robes. He was very modern. In England, he wore Savile Row suits, and in India, dhoti kurta.”

Alluri would probably never have met Eyres except that he came across an article on Krishnamurti the latter had written in the Financial Times in 2005. Eyres had visited the Krishnamurti Foundation centre in Brockwood Park, set in idyllic Hampshire countryside. The place offers “individual and group retreats for those wishing to inquire into themselves, in light of Krishnamurti’s teachings”.

After reading his article, Alluri contacted Eyres and suggested they collaborate on a book.

The Englishman’s back story is just as fascinating. It explains why Krishnamurti’s appeal is international – there are Krishnamurti Foundation Trusts in the US, Latin America (with headquarters in Spain) and in the UK.

Eyres has written: “A relatively early one of the 500 or so columns I wrote for the FT’s international audience was about the Indian sage and educationalist Jiddu Krishnamurti; I’d decamped to the Krishnamurti Centre at Brockwood Park in Hampshire to avoid a UK general election campaign which I considered mildly poisonous.

“I’d become interested in Krishnamurti having been introduced to him by a potter friend. I read a number of his books and then visited Chennai, where he lived as a boy and was discovered by the luminaries of the Theosophical Society, who proclaimed him to be the next ‘World Teacher’. From Chennai I travelled to Rishi Valley School in Andhra Pradesh, which he founded in the 1920s on land – now a bird sanctuary – close to the village where he was born.

“Gurus held little appeal for me but Krishnamurti (or K as he is often known), as I wrote in the column, was an anti-guru. I loved the fact that he’d renounced the title of ‘World Teacher’ and all the trappings that went with it. I saw him as a kind of latter-day Socrates, though with a more holistic interest in the workings of the mind, not just logic or reason.”

Eyres went on: “That column, which was for a while displayed at Brockwood Park, came to the attention of Vishwanath Alluri. Vish was a highly successful tech entrepreneur who had become secretary of the Krishnamurti Foundation India, involved in the dissemination of Krishnamurti’s teachings and the education of teachers.

“Vish got in touch with me and asked if I might be interested in co-writing a book which looked at management and entrepreneurship through the lens of K’s teachings. I met Vish in London and immediately liked and was impressed by him, but had to explain that I was a complete ignoramus on the subjects of management and entrepreneurship. That didn’t matter, Vish assured me: we would both learn as we went along.”

His FT column was introduced to readers with the standfirst: “Rare retreat without restrictions. Feeling bombarded by political shenanigans? Peace and solitude can be found at the Krishnamurti Centre in Hampshire, where goodness flows.”

Eyres said that “the most remarkable thing about Brockwood is the way it is pervaded by the spirit of a truly extraordinary man. Many will know the bizarre story of J Krishnamurti: how a poor South Indian boy was adopted by the Theosophists Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater and educated by them to become a new, global Messiah; and then how the young Krishnamurti dramatically disavowed these messianic intentions, declared that ‘truth is a pathless land’ and set out on his own six-decade-long pilgrimage as a philosophical and religious teacher or guiding light, though he insisted, like Socrates, that he was not really a teacher at all. He was, however, an educationalist, who founded half a dozen schools, which privilege the development of a rounded, ethical individual over the accumulation of information and grades. One is housed near the centre in Brockwood Park. Krishnamurti was an antiguru. He was certainly very different from, and often scornful of, those gurus who demanded or attracted unquestioning devotion, and accumulated scores of Rolls-Royces, jewels or palaces.”

That might have been a dig at Osho Rajneesh (Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh), the Indian guru famously known for owning a massive collection of 93 Rolls-Royces in the 1980s.

Eyres wrote about Krishnamurti as an environmentalist: “Long before our current, belated recognition of ecological crisis, he saw how ‘we have destroyed the earth, polluted it, wiped out species. Killing animals has become an industry.’ At the Rishi Valley school in Andhra Pradesh, India (a marvellous place to visit if you have time), he undertook the planting of thousands of trees and created a bird sanctuary in what had been a near-desert. What struck me most on my last visit to Brockwood, though, was Krishnamurti’s inspiring loftiness of purpose – his dedication to the truly good and beautiful and marvellous that can come about in the here and now, and need not be sought in the beyond.”

The book, Enlightened Manager, is written in the form of a conversation between three people.

Vishwanath Alluri becomes “GP”, a nickname from his childhood days, while Harry Eyres, whose full name is Harry Charles Eyres, is referred to as “HC”.

A third character, “Panna”, who brings the wisdom of village India, has been invented.

The three chat among themselves on anything and everything as they take a journey from Hyderabad to Bangalore.

Krishnamurti is called “the friend on the bench”.

Eyres, who has done the actual writing because Alluri favoured an English pen to explain Indian thinking, has set out the contours of the journey which is partly geographical but also spiritual: “The process was quite slow and organic, partly because of geography and Covid, partly no doubt because of my slow cast of mind. I decided to frame the book as a road trip, based partly on a real road trip we made from Vish’s home city of Hyderabad to Rishi Valley school, whose core consisted of a series of conversations between an entrepreneur and a writer, not entirely dissimilar from Vish and me.

“Quite slowly at first, and then much more quickly, the book came to birth. I hope at the very least it’s unlike most other business books, that it may puncture a certain amount of business bombast and hype, and that it may introduce readers to a quiet source of insight, above all into their own minds. Because that’s where we all have to start.”

Eyres has said he has found that Krishnamurti’s insights provide a vital, “slow” alternative to the frantic pace of modern professional life.

For example, Eyres has “used Krishnamurti’s teachings to challenge traditional, often mechanical, management styles”. He has emphasised “true effectiveness comes from understanding the self, rather than merely acquiring knowledge or following rigid strategies”. He has also explored how, according to Krishnamurti, “true meditation is not a technique but a way of being fully present and aware in daily, often busy, life”.

The book is not meant to be read in one sitting but appreciated in small sips.

Its publicists say that “Alluri and Eyres have teamed up to think through the management problems of today in the light of Krishnamurti’s timeless insights. Can we be more productive and make better decisions by becoming radically self-aware? How can humility and compassion make us more effective leaders? Is there more wisdom in a single story about a man pushing a bus, than in a hundred strategy powerpoints?”

Alluri discovered he and Eyres shared a love of tennis, which is why Roger Federer makes an appearance in the book. The point being made is that Federer is more of an artist, who plays tennis because he loves the game rather than to make money.

His logic is that people should not become obsessed with “outcomes”. What is more important is the “process”.

GP (Alluri) says in the book: “In my view Roger Federer has transformed the art of tennis watching. Federer has brought a whole new phalanx of viewers to tennis, who are attracted not for nationalistic or chauvinistic reasons, or even just because of success and winning, but because of the relationship with the beauty that is manifested in his game. This cuts across all ages, nationalities and religions. Federer has transformed the relationship of viewers to the game. Until he came on the scene most of the time, for most people, it was just watching a sport, but with Federer playing, for spectators all over the world it became watching not just sport, but sharing the experience of beauty and art. With this he brought many new viewers to tennis.”

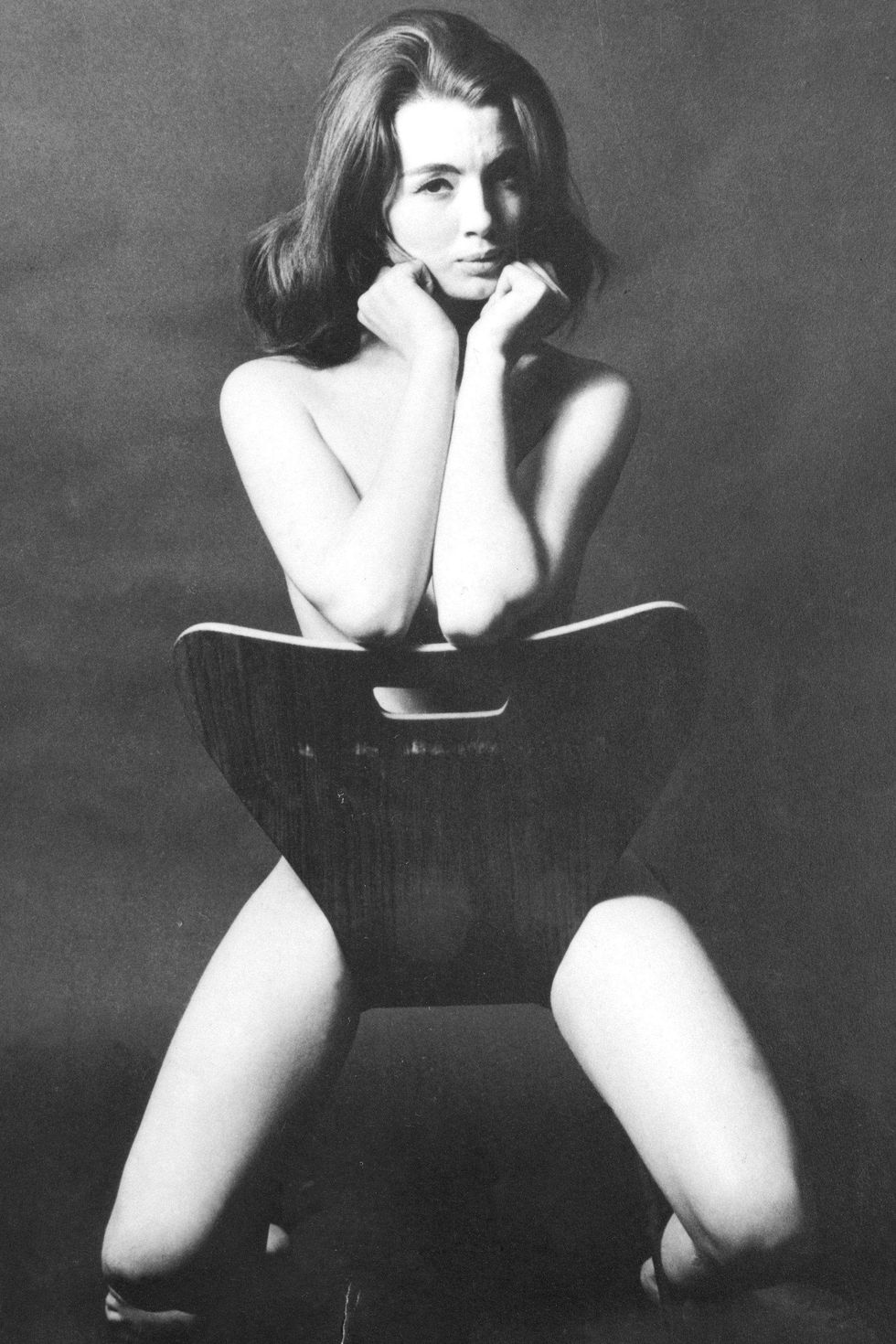

Rather more surprisingly, Eyres brings up the Profumo Scandal, which was an obsession in 1960s Britain even more than Lord Peter Mandelson is today because of the latter’s links with the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

HC (Eyres) recounts: “‘A fascinating story. So here is my tale. It concerns the British politician John Profumo, and it could be subtitled: why do we pursue sex at all costs? You may ask, why Profumo? He was a politician and not a manager. Well, I would answer that he is a human being in the first place. Even a manager is a human being in the first place. All human beings have the same vulnerabilities.

‘So Profumo served as Secretary of State for War in the cabinet of the Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. Profumo met a 19-year-old would-be model called Christine Keeler at a house party at Cliveden, the home of Lord Astor, in July 1961. They began an affair. Keeler was then living with the society osteopath Dr Stephen Ward. Ward was very well connected, through his practice, with high society circles and liked to give somewhat louche parties. Profumo sometimes met Keeler at Ward’s house. Another acquaintance of Ward, and Profumo, was a Russian naval attaché, Captain Yevgeny Ivanov, with whom Keeler had also had a brief relationship.

“Profumo made a statement to the House of Commons denying any impropriety in his relationship with Ms Keeler. But the rumours intensified and press reports hinting at the relationships between Profumo, Keeler and Ivanov appeared. Ward was investigated and then charged by the police for living off immoral earnings. Under this pressure, despite publicly backing Profumo, Ward indicated to Profumo’s private secretary and to the Home Secretary that embarrassing revelations might emerge. The Prime Minister, who had previously supported Profumo, summoned him back to London from a holiday with his wife in Venice and Profumo admitted having lied to the House of Commons. He tendered his resignation. He never returned to politics but spent the rest of his working life in the charitable sector. In a recent BBC TV dramatisation of the events, Profumo’s rather laconic wife makes the comment, ‘I hope she was worth it.’ ”

Eastern Eye asked Alluri how the Profumo scandal was relevant to the theme of the book on how to be an enlightened manager.

“John Profumo figures in the chapter on work-life balance,” Alluri replied. “It is explained that three factors have the potential to destabilise this balance. They are ‘MSF’ (money, sex and fame). We have taken real world example of these.”

The gist of the message in his book that for someone to become an enlightened manager, he (or she) first has to understand himself.

“If a manager’s job is to manage people, it implies he has to manage other minds,” stated Alluri. “If this is so, it is imperative that he has to understand how his own mind is operating. If he doesn’t know his own mind, how can he manage other minds?”

He elaborated: “K’s teachings are essentially about the psychological structure of human beings. They are all practical as they address human problems directly and not through any philosophy. There are so many things K talked of that are applicable in this respect. For example, on work-life balance, he talked of the value of a pause in the day.”

Alluri stressed the importance of awareness.

He gave the example of the Indian cricketer Mohammed Siraj who caught the England’s star batsman Harry Brook on the fine leg boundary in the Oval Test last year but inadvertently stepped over the boundary (a similar incident takes places in the Bollywood blockbuster, Lagaan).

“Siraj had awareness but his awareness was fragmented,” commented Alluri. “Fragmentary awareness leads to mediocrity. That is the point we are making.”

The book also deals with the “conditioning” that shapes human beings.

Alluri said: “Conditioning refers to cultural, sociological, political, religious matters. For instance, as an Indian I am conditioned as a Hindu, Indian, a Telugu man etc. These factors have an origin that goes back over thousands of years. Most of the conditioning gets into deeper layers of consciousness. We may refer to this as subconsciousness. These factors play great role in our lives.”

The Enlightened Manager: A Transformative Approach to Work and Life. By Vishwanath Alluri with Harry Eyres. Published by Harper Business, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Available on Amazon for £9.99