SIX months have passed since the evil murders in Southport triggered six days of senseless violence.

Rioters terrified Muslim worshippers at the town’s mosque, tried to burn asylum seekers alive at a Rotherham hotel, and spread fear among ethnic minorities across the country by posting targets for a pogrom of future violence.

Did that terrifying violence show that the idea there has been progress against racism in Britain is a mirage? It is not surprising that the question is asked, but the lesson is a subtly different one. There has been significant progress against racism in our lifetimes, especially across the generations. What the violence showed is that progress remains uneven, insufficient and incomplete – in ways that mean the challenges for tackling racism in Britain today are changing.

To focus too much on “misinformation” risks characterising racist rage as merely misdirected. It is not as if mobs should have targeted the Christian church attended by the parents of the perpetrator. If the viral online rumours that the killer was an asylum seeker or a Muslim had been true, that would not have made other people with those backgrounds a legitimate target. The targeting of those groups reflected underlying patterns of fear and prejudice in our society.

One key lesson is that anti-racism and cohesion must be two sides of the same coin. It makes little sense to think of them as an either/or choice for policymakers. Cohesion is about the glue that holds us together. Sustained meaningful contact can build shared identities and resilience when cohesion is tested by shock events. That depends on conditions of equal status and mutual respect to be effective: so racism is a barrier to cohesion and tackling it a precondition for success.

The new Labour government took rapid action to quell last summer’s disorder. Addressing its causes may take longer. There were one-off grants to areas that experienced disorder, going mostly to places of below average diversity. Work on a broader communities strategy is ongoing.

More needs to be done to extend basic anti-racism norms to cover those seeking asylum. The language used to drive out “illegals” in Rotherham made me reflect on how my instinctive response to racists since I was a teenager – that there was nowhere to send me “back” to – was expressing a birthright privilege that asylum seekers do not share.

The targeting of Muslims highlights how anti-Muslim prejudice is more widespread than prejudice against most other minority groups. Yet, the new Keir Starmer government inherited a policy vacuum on anti-Muslim prejudice: no working definition; no independent adviser to lead the work; nor any sustained forum of engagement with Muslim civil society. There are reports that former Conservative Attorney-General Dominic Grieve may now be asked to play a role.

Few words have created more heated civic and political debate than “Islamophobia” over the past two decades. It is hard to have effective national or local action without any definition to work with. Many organisations signed up to an APPG definition, usually to show solidarity by agreeing with what was on offer. Yet the term Islamophobia confuses a key boundary. Putting the name of the faith, ‘Islam’, first – rather than that of the followers, ‘Muslims’ – is bound to generate confusion, with critics arguing it may create a backdoor blasphemy law, even if the aim is to protect people from prejudice, not their faith from criticism.

Yet there is the potential for common ground. Most people would agree that it is not Islamophobic to critique ideas from a faith or political perspective; nor to debate, in good faith, the integration challenges in Britain today. What crosses the line from politics to prejudice is to discriminate against Muslims for being Muslims or to hold all Muslims responsible for the actions of an extreme minority. One useful prejudice litmus test is which types of conversations about Muslims would probably stop if, for example, a Muslim walked into the room.

Definitions can only be a starting point for action. The riots did not reflect “who we really are”: the counterprotests had a stronger claim to do that. But the attitudes that underpin the violence are part of our society too. It will not be enough to have threequarters of society agreeing that racist violence is a bad thing, without effective action to address the corrosive impacts of the toxic minority too.

The riots show how progress shifting mainstream norms on race and prejudice, and its limits, mean that anti-racism faces new challenges in this decade. One challenge is to build the effective mainstream coalitions for stronger policy action. Another is to identify the methods and alliances that can reach and persuade the toughest quarter of society still holding casual prejudices and toxic attitudes that threaten the fairness, safety and cohesion of our country.

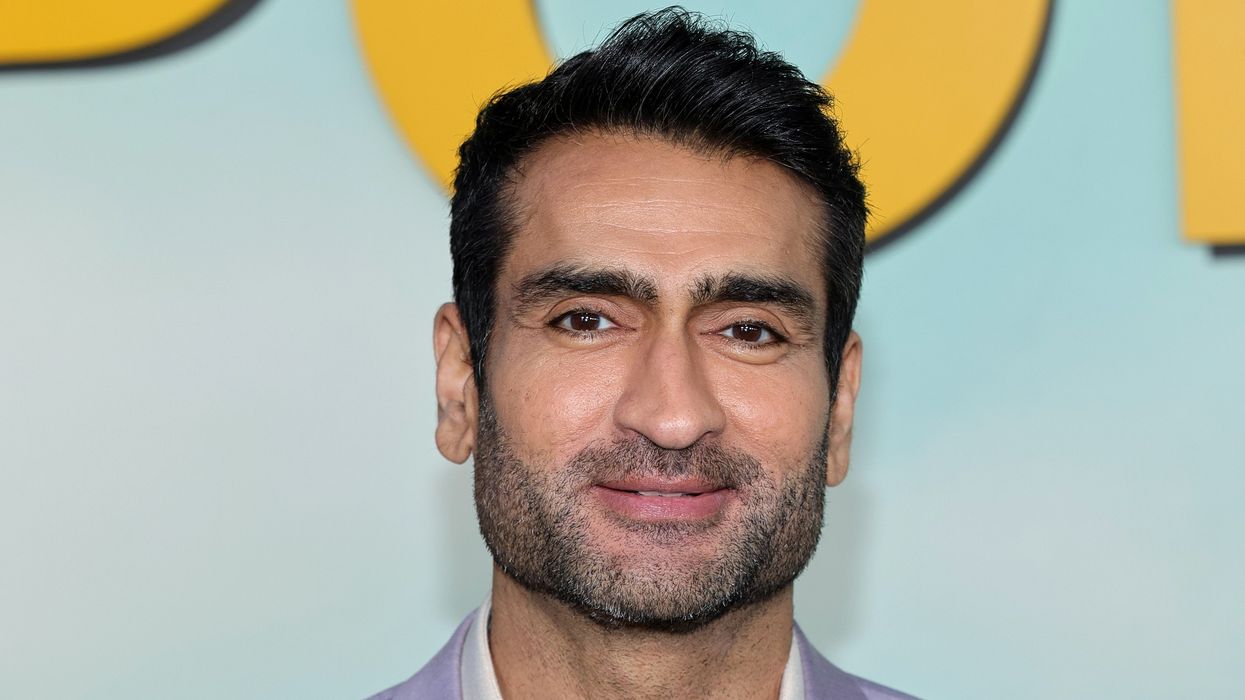

Sunder Katwala is the director of thinktank British Future and the author of the book How to Be a Patriot: The must-read book on British national identity and immigration