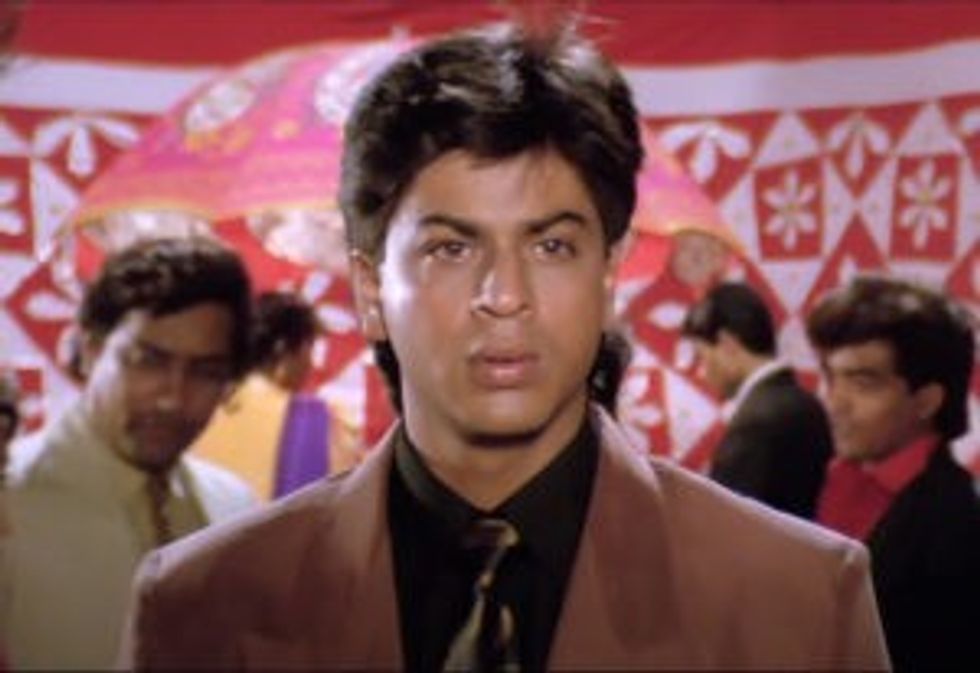

SHAH RUKH KHAN took his first major steps towards global stardom by playing distinctly different villainous roles in quick succession in one year with Baazigar, Darr and Anjaam.

Although it was the least successful of the three, Anjaam, released on April 22, 1994, perhaps doesn’t get the credit it deserves. It had plenty to offer audiences, from an iconic dance number to a memorable avenging angel played by Madhuri.

The film revolves around an obsessive lover destroying the life of a married woman and her battling against the odds to fight back in a unique way. To mark the movie’s 30th anniversary this month, Eastern Eye put together some top Anjaam trivia.

■ The dark drama was originally titled Majnoon Ka Junoon before it was changed to Anjaam.

■ Bollywood’s number one actor at the time, Anil Kapoor, was the original choice to play the lead role, but he turned it down.

■ The two biggest movie stars of the 1990s were Madhuri Dixit and Shah Rukh Khan. Anjaam was the first time they worked together, before going on to star in successful films such as Dil To Pagal Hai and Devdas.

■ The original choice to play the female lead was the older actress Rekha, but things didn’t work out, and Madhuri stepped into the role.

■ The opening credits didn’t appear until 30 minutes into the movie.

■ It has been widely reported across the years that lyricist Sameer and music duo Anand Milind had composed the song Badi Mushkil Hai for the 1990 hit film Dil, but director Inder Kumar had rejected it. Four years later, they decided to use it for Anjaam. When asked about this, Anjaam director Rahul Rawail denied it and said the song was specifically created for his film

■ The song, Ye Kaali Kaali Aankhien, from Baazigar is sung multiple times by comedian Johnny Lever, who had also previously starred in the same film alongside Shah Rukh

■ British music legend Apache Indian’s song Chok There is played during a nightclub sequence in the movie.

■ A moment in the song Badi Mushkil Hai where Shah Rukh emerges out of the taxi trunk and climbs onto the roof of the moving car went viral on social media a few years ago.

■ Channe Ke Khet Mein became a big highlight in the movie and was copied by dancers around the world later, including the iconic spin

■ Madhuri revealed that another song was supposed to be used instead of Channe Ke Khet Mein, but she, along with dance choreographer Saroj Khan, didn’t find it fun enough and asked the director to change it. She had said: “We went up to him and said the song wasn’t good enough. He asked the music directors to work out something else. That’s how Channe Ke Khet Mein came about. We had liked the song then. But I didn’t know it would grow to be so popular. People perform it in reality shows even today.”

■ One YouTube video of Channe Ke Khet Mein has been viewed nearly 60 million times in the past three years. There are videos of film fans performing the same song on the video sharing site. The song would also be remixed and sampled in many pop albums.

■ The song Barson Ke Baad, where Madhuri performs for a wheelchair-bound Shah Rukh was shot in single take. Madhuri recalled: “Three-four cameras were placed in different angles. I had to remember, which camera was where in keeping with whether I had to give a profile or a long shot.

We rehearsed for it. Thankfully, it got okayed in one take. Shah Rukh, being on the wheelchair, had just to watch me.”

■ Much of the movie was shot in Mauritius.

■ In the original ending, only Shah Rukh’s evil character was supposed to die, but was changed to the heroine sacrificing her life because of the dark deeds she had been forced to commit.

■ Deepak Tijori said Anjaam was the only film he regretted doing and that he had got a raw deal, with his character having very little to do. Tijori was omitted from all the publicity material of the movie, with Madhuri and Shah Rukh dominating the posters. He said: “The script was not ready. The director (Rahul Rawail) started writing a script completely in favour of Madhuri Dixit."

■ Shah Rukh’s wife, Gauri Khan, was credited as one of the costume designers in the movie.

■ Shah Rukh won a best villain trophy at the Filmfare Awards after failing to win it the previous year for Darr.

■ Madhuri earned a Filmfare best actress nomination for Anjaam, but won instead for her performance in the record-breaking musical Hum Aapke Hain Kaun.

■ While Baazigar and Darr were in the top five highest grossing movies in 1993, Anjaam failed to enter the top 10 of 1994. But it did do higher business internationally than in India.

■ Most agree the unapologetically sociopathic character played by Shah Rukh in Anjaam is far more menacing than any he had played up until that point. It remains arguably the most negative character of his career.

■ In a later interview, Madhuri reflected that Anjaam didn’t work because of the excessive violence and had even asked for some portions of the film to be edited out.

■ Shah Rukh would later buy the rights for the movie and now his production house Red Chillies Entertainment owns it.