THIS must be a “tipping point” for the rule of law online, technology secretary Liz Kendall told the House of Commons earlier this week. X owner Elon Musk’s Grok AI tool helped that site’s users make sexist harassment the viral new year trend of 2026. Politicians across the world declared it was “appalling” and “unacceptable”. The challenge is to turn that declaratory rhetoric into action. Britain’s media regulator Ofcom will open a formal investigation.

The controversy has illuminated again how US billionaire businessman Musk takes a “pick and mix” approach as to which laws he thinks should apply to him and his companies. Even libertarian site owners tend to recognise some responsibility to remove child sexual abuse. But Musk was laughing about the nudification trend. He is contemptuous about laws curbing hate crime and the incitement of violence, saying they are signs Britain has a “fascist” government which must be overthrown. What is vital is that our government and regulators do not risk emulating Musk’s “pick and mix” approach to when unlawful content really matters. Ofcom states it will not “hesitate to investigate” when it suspects companies are failing in their duties “especially where there’s a risk of harm to children”. This will be a popular public priority. Ofcom must this year show parliamentarians and the public that it can find the bandwidth and capacity to insist on sites meeting all of their legal duties.

Ofcom has more hesitantly begun a programme to explore if major sites have compliance failures on hate crimes. Any good faith investigation ought to be able to move beyond that question of “if” to open a formal public investigation of specific platforms. Reports of hate crimes – abusing people with the racial slur “P***” – is protected by the Twitter/X complaints system 95 per cent of the time. Any mystery shopping research could emulate that test across every form of unlawful content. A root cause of X’s systemic failure is that it simply does not have a functioning complaints system, probably by both accident and design, with almost no staff to provide human oversight of the most egregious failures.

The government has pressed Ofcom to prioritise action on antisemitism, rightly reinforcing that after the Manchester synagogue tragedy. But even as ministers worry out loud about a resurgence of “the racism of the 1970s” experienced by NHS staff and others, the government has yet to join the dots to how racism is being legitimised online.

Racist trolls openly boast about their sense of impunity to commit more crimes. “A huge congratulations to Elon Musk and the Britain loving patriots at X”, one stalker who had incessantly abused me and others with the P-word for months, posted. The police wanted to prosecute. X refused to share the details. He dreamt of prosecuting the police for being race traitors after the revolution. Platforms may cooperate with police over the most serious terrorist offences, but they also routinely refuse police requests about racist and misogynistic hate crimes. The data about how often that happens should be made public too.

There are clearly cross-party pressures on a nervous government. Britain’s laws on online harms are new and untested. The administration of US president Donald Trump does not believe in international law constraining America – but may threaten democratic governments over domestic laws.

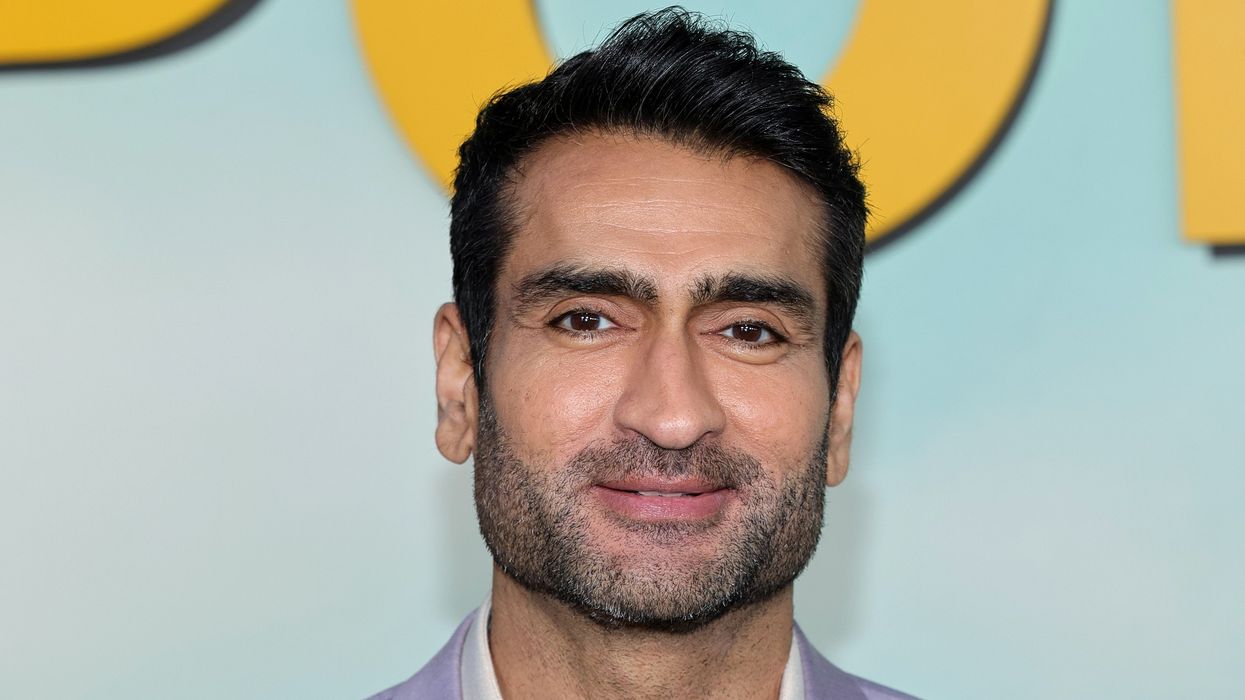

Beyond child abuse imagery and nudification, there is a heated political debate about the boundary between hate speech and free speech. Yet a show-and-tell approach to the type of racist abuse that X is protecting – against targets from Reform’s Zia Yusuf to Zarah Sultana – would command a near universal consensus too.

Many in the Westminster bubble underestimates the loss of X’s reach – it has shed a third of its British users under Musk – as a deeply misinformed ministerial statement exaggerating its public reach in the Lords last week showed.

The core argument should be that nobody is too rich or powerful to be outside the law. It is not ‘censorship’ to insist every website operating in our country does so within the law. Fines may be ineffective – if treated as a cost of doing business – until the sanctions for not paying include risking a licence to operate, temporarily or permanently.

Musk – the world’s richest man – wants to be the greatest global influencer too: a Citizen Kane for our age. All the money in the world could not get the fictionalised media baron in Orson Welles’ 1940s film everything he wanted. Almost everyone in the Commons and beyond it agreed that Citizen Musk has gone too far. The peculiar genius of the increasingly radicalised Musk may deliver a surprising paradox: this powerful agent of this age of polarisation could help Britain find common ground on foundational norms. The core task could fit on a Trump-style baseball cap: it is time to Make Social Media Lawful Again.